No sex, no drugs and definitely no Sid Vicious

Sex Pistol Sid Vicious didn’t merit a mention when he died – nor did Buddy Holly. Now the colourful lives and deaths of pop stars are a staple of its pages, writes The Times obituary editor.

‘I believe they are a popular beat combo, m’lud.” That, supposedly, was the answer given by a barrister towards the end of the Swinging ’60s when a British judge asked in court: “Who are the Beatles?”

The exchange seems improbable now, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen then. And if it did, I can guess the reason. Around that time there was a famous advertising campaign with the slogan “Top people take The Times. Do you?”. Those top people will have included members of the judiciary.

And who might those top people have expected to read about when they opened their paper of choice? In the obituaries section it would have been the great and the good: archbishops, captains of industry and ambassadors, several thousand words on each. And war heroes, of course.

Figures from high culture would be covered too, but when it came to music this would mean opera sopranos, classical composers and conductors. The low culture of rock and pop? Not so much. When Buddy Holly died in a plane crash in 1959, he didn’t merit an obit in The Times. Buddy. Holly.

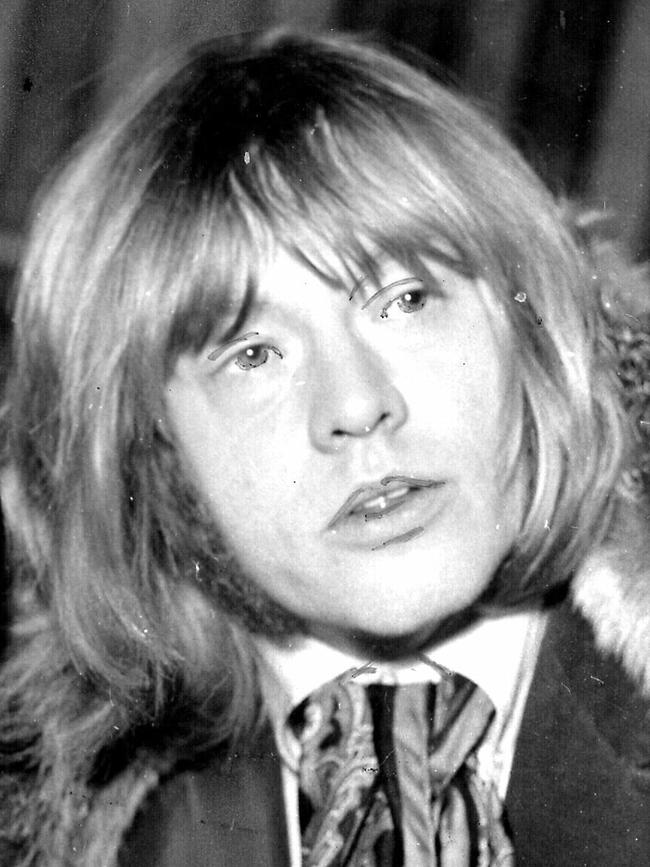

By the late 1960s pop stars were starting to get Times obituaries, but almost begrudgingly, in a perfunctory and formal way. Mr Brian Jones, as he was styled, got a modest and dry 500 words in 1969, even though the news that the Rolling Stones founder and guitarist had been found dead in a swimming pool was making front pages round the world.

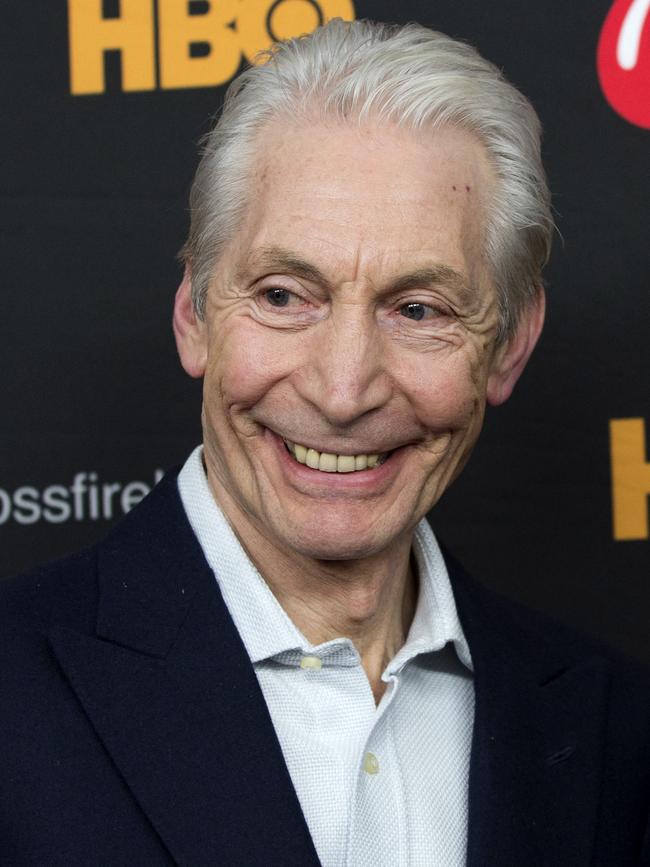

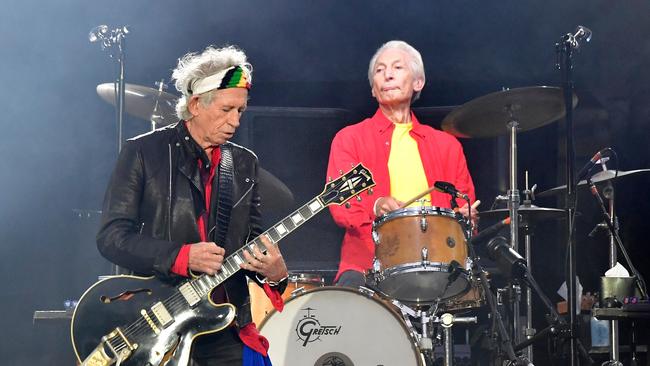

By contrast, when Charlie Watts, the Stones’ drummer, died in much less dramatic fashion in 2021, I, as the obits editor of The Times, allotted him 3000 words. I also thought we could probably, on balance, get away with dropping the “Mr”.

What was behind this cultural change of heart? Well, The Times has always taken seriously its role as “the newspaper of public record”, and back then it took the role very seriously indeed – so seriously it didn’t introduce bylines for writers until the mid-1960s, and certainly didn’t include anything as frivolous as a colour supplement full of lifestyle features, diet tips and celebrity interviews.

It was the broadsheet of the establishment, and the establishment wore suits and listened to classical music. They didn’t wear kaftans and listen to pop. You can get a sense of these “two cultures” when you watch footage of the Beatles’ rooftop concert in 1969. That beat combo are up there with their long hair, flares and Afghan coats while down in the streets below, looking up in bemusement, are the top people, the City types with their bowler hats and furled umbrellas.

Not everyone, it seems, got the memo about the youth-driven cultural revolution that was the Swinging ’60s. Another illustration: Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band may have been the biggest-selling album of 1967, but it wasn’t the biggest of the decade. That would be – yes, you haven’t guessed it – The Sound of Music.

The tone of the obits was quite stuffy and obfusc back then, too, and this continued into the next decade. Consider the way the 1977 obit for Mr Elvis Presley earnestly notes the “negro” roots of his style of rock’n’roll, or the way the obit for Mr Keith Moon in 1978 requires quote marks around “The Who”, then as now one of the most famous bands in the world.

Also then as now, Times obituaries were unsigned, but if you had to guess who wrote Mr John Lennon’s from 1980, you might say it was the paper’s classical music critic, such is its lofty, slightly patronising tone. It makes no mention of bed-ins, LSD or Imagine, but it does include the sizzling line, “the Cavern Club in Liverpool, one of the foci of the new Merseyside sound”.

Private lives tend not to be mentioned either, just careers. The obit for Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys, who died in 1983, is fascinating for what it doesn’t say. He was one of the most colourful figures in pop history, yet there is no mention of the mysteries surrounding his death, nor his heroin addiction and epic sexual promiscuity. The $US100,000 he donated to the Charles Manson “family"? Not a whisper. His obit doesn’t even acknowledge that he was the only member of the Beach Boys who surfed.

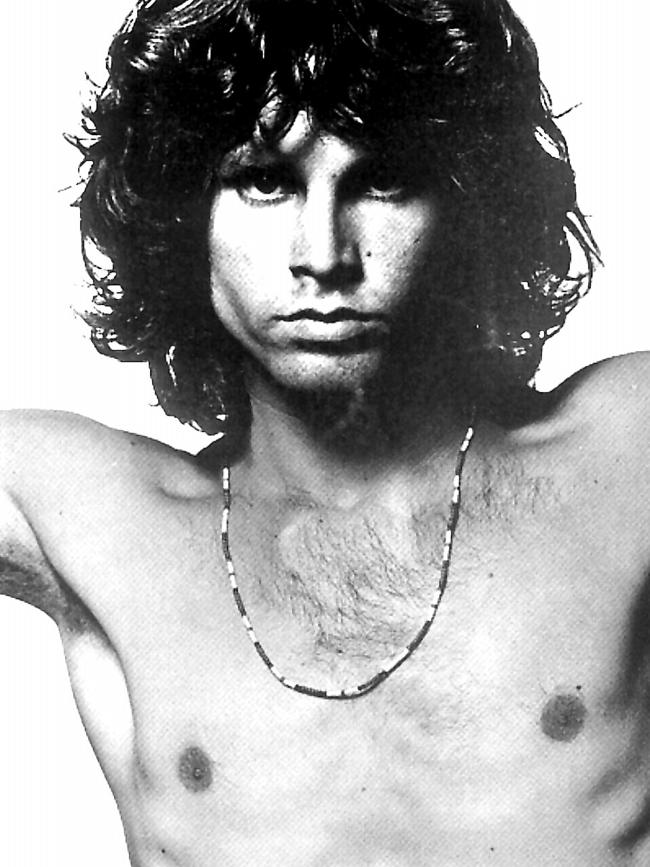

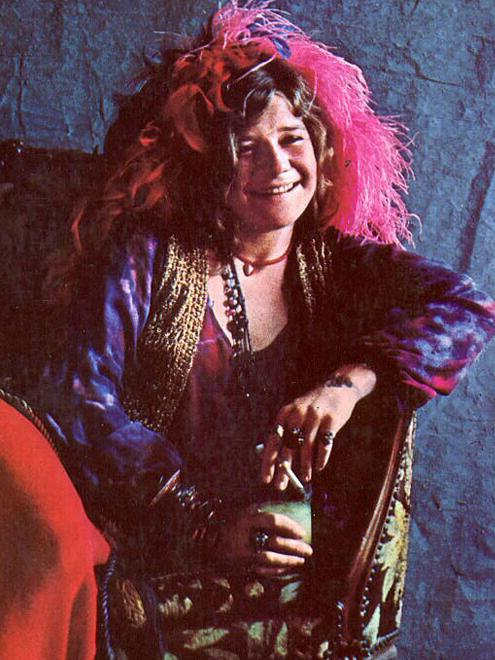

These drier, shorter early obits, then, are portals to a bygone age, a reminder that the past is another country. I’ve included a handful of them in a new collection to demonstrate what I mean: Mr Jim Morrison and Miss Janis Joplin feature, for example, as well as another member of the infamous “27 Club”, Mr Jimi Hendrix. No mention is made of his assiduous drug taking or his performance at Woodstock, but rather sweetly the obit does note that his music was “awesomely loud”.

By the time Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse joined that club of pop stars who died at the tender age of 27, not only had the titles been dropped, but the obits were getting a bit longer and more in depth, covering the sex and drugs as well as the rock’n’roll.

Yet even theirs aren’t the most dramatic stories of rock-star excess you will find in this new collection. Take Glen Campbell’s. He may have been a God-fearing country-and-western star, but his lifestyle was pure destructive, pagan rock god. His addictions to cocaine, bourbon and wild women, indeed, rivalled the feral appetites of the most hedonistic rock’n’roller.

In a strong field, though, it is Ginger Baker, the drummer of Cream, who was the maddest, baddest and most dangerous rock star to know. He had feuds with everyone and would use violence as a first resort, thinking nothing of breaking a nose or pulling a knife on a bandmate. Eric Clapton professed to be properly scared of him.

Against all the odds, and despite his epic, lifelong consumption of class A drugs, Baker lived to the ripe old age of 80. Even he seemed surprised by this.

Nowadays, obituaries of rock and pop stars are more like long-form features: writerly, full of lively anecdotes, wry. And we hear the subject’s voice through quotation. I was tempted to expand some of the older pop obits not styled in this way, such as that for Freddie Mercury, but I’ve kept them as written at the time on the grounds that they intrigue more as undisturbed time capsules, as first drafts of history.

Inevitably, perhaps, we on the obits desk have come to think of those rock stars who did manage to survive the excesses of the ’60s. and ’70s. as “the new few”. This, after all, is a profession where, as “The Who” memorably put it, people hoped to die before they got old. Alongside the drug overdoses, causes of death listed in the collection include suicides, murders and car crashes.

But all too often it is something more commonplace. David Bowie choreographed his departure beautifully, releasing his final single and video, Lazarus, as a moving self-epitaph on his 69th birthday in 2016. It was extraordinarily artful, and in complete contrast to the cause of his death two days later, which could scarcely have been more ordinary: cancer.

Traditionally, obituaries for stars of his stature would always be run in print the next day, but now there is an additional need for speed: digital. The Times obit for Charlie Watts appeared online within minutes of his death being announced one afternoon.

We know such obits are popular with our readers because, owing to the latest technology, we can see how long they are spending with each story. Obituaries that appear online quickly have a long “dwell” time because sometimes the thing you most want to read when someone famous dies is a short biography with a satisfying beginning, middle and end.

Print still matters. News of Olivia Newton-John’s demise in 2022 was less kind in terms of timing because it broke at 8pm and our print deadline meant her two pages would have to be designed and “revise subbed’‘ by 9pm – but we managed thanks to one of the worst-kept secrets in journalism, namely that we on the obits desk spend a lot of our working day prepping the “household names” in advance. They are called stocks, as in stockpile, and we usually have about 3500 of them in a fairly up-to-date state.

Who we prepare in advance often has more to do with fame than age or ill-health. Big names such as Elton John, Rod Stewart and Keith Richards are all teed up, for example. And Mick Jagger, of course. Incidentally, he once asked to see his. (Hello? Control freak.) We declined to show him and he accepted our reasoning with good grace. Paul McCartney’s was first prepared for The Times in 1967 by none other than Hunter Davies when he was spending a year with the Beatles writing their authorised biography. His obit for McCartney then was the standard 500 words. The latest iteration, written by our chief music obits writer, Nigel Williamson, is 3000 words long.

Williamson, an author, music critic and interviewer of pop stars, has been doing this job for quite a few years now and recalls that Ian Brunskill, one of my predecessors as obits editor, was “the ultimate ambulance chaser. A celeb only had to sneeze and Ian commissioned a stock. His best line was ‘I saw Lou Reed on The Old Grey Whistle Test at the weekend. He looked a bit peaky. You’d better do him’. To which I replied: ‘Lou Reed has been looking peaky since 1966 when he was only 24. It’s called heroin’ ”.

Inevitably, there wasn’t room for all the fallen rock and pop stars from the past six decades, but I’ve tried to include a good mix of male and female, British and American, black and white. I’ve also gone for a cross-section of genres, from rock’n’roll, psychedelic, prog, glam and heavy metal, to disco, punk, C&W, new romantic, ska and grunge.

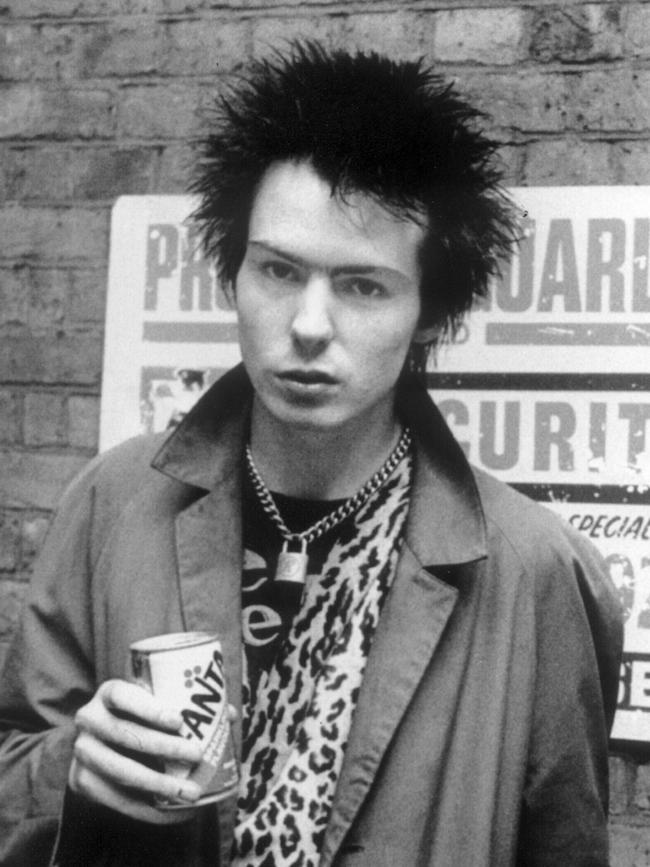

One omission you may notice is Sid Vicious, the Sex Pistols bassist and singer, who died of a heroin overdose at 21 in 1977 after allegedly murdering his girlfriend, Nancy Spungen.

That’s because this legend of popular culture was not deemed suitable for an obit back then. But times change, and The Times changes with them. Nowadays he would be a double-page spread.

The Times

Lives Behind the Music: Era-Defining Obituaries of Rock and Pop Icons, edited by Nigel Farndale. (HarperCollins ebook, $16.99. Printed edition, January 2025).