No. 10’s culture problems all stem from Boris Johnson

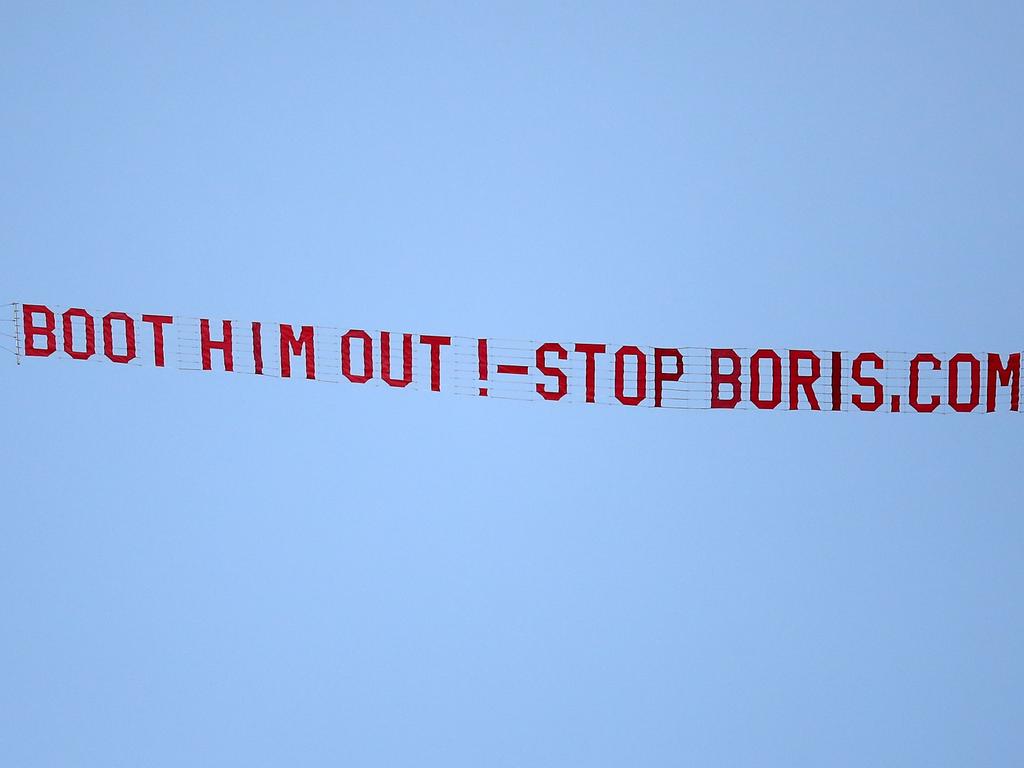

For today, as we all wait for Sue Gray and she waits for someone else, there seems to be plenty of people questioning the very idea of ministerial accountability.

Dugdale was a minor cabinet minister who ended up leaving the government in 1954 as the result of an almost impossibly obscure dispute. In 1938 the government had made a compulsory purchase of a piece of land, Crichel Down, for RAF bombing practice; Churchill later promised parliament that it would be returned to its owners after the war. This promise was not kept; the resulting fuss led to a public inquiry.

The inquiry criticised the behaviour of civil servants and Dugdale offered his resignation, even though his own actions weren’t being questioned. His resignation was accepted and immediately was regarded as establishing an important precedent. Ministers were accountable for their departments, not only their own behaviour.

Citing Crichel Down has rather fallen out of fashion. Its precedent has rarely been followed. Lord Carrington’s resignation as foreign secretary over the invasion of the Falklands is often cited; as, sometimes, is the decision of Estelle Morris to resign as education secretary in 2002 when some ministerial targets were not met. Yet these were about broad policy failures rather than responsibility for scandal.

Roy Jenkins did not have to resign as home secretary in 1966 over the escape from prison of the spy George Blake, nor did William Whitelaw in 1982 after the intruder Michael Fagan managed to get into the Queen’s bedroom, nor did Michael Howard in 1995 after a series of prison escapes. The last of these three sacked the head of the prison service after a critical inquiry.

In fact the story of Dugdale’s honourable resignation no longer looks even like a good description of the Crichel Down affair itself. Subsequent government papers have shown the policy was Dugdale’s all along. Which, as many constitutional experts agree, has left open the question of what exactly ministers are accountable for. And through this gap, the defenders of Boris Johnson have, in the last couple of weeks, been pouring.

No one can any longer deny that there was a series of events in Downing Street – some were parties, others were gatherings – that broke the rules the government set for everyone else. Sue Gray, and now the police, are trying to establish who exactly was involved, and how often.

It is accepted that if the facts show unequivocally that the prime minister knowingly lied to parliament, he would have to go. But this is a fairly high bar. The report may well not vault it. And if, instead, it merely shows that there was an epidemic of rule-breaking in No 10, into which the prime minister more or less unwittingly stumbled, Conservative MPs may deem him exonerated.

Plan for deputy heads to roll

The suggestion is that he must be held accountable for his own actions and statements but not for those of his staff. But is that a doctrine of ministerial accountability we are willing to accept? I do not think it should be.

The plan appears to be for deputy heads to roll. The most often identified deputy head is that of the chief of staff Dan Rosenfield. The prime minister will announce that the “culture of No 10” has to change. Key personnel will be removed. Key personnel will be appointed. Sorries will be said. And on we will all go.

If the attempt to put the blame on Rosenfield were not such a serious evasion of duty and leadership, it would be funny. When all these parties were taking place, Rosenfield wasn’t even working there. He was the person the prime minister put in place when he blamed the last lot of senior advisers for the chaos in No 10.

Fortunately, events have provided us with impeccable information on where the culture of disarray and dissembling in Downing Street might have come from. If we employed a social scientist to conduct an experiment they couldn’t have done a better job.

First, we have tried varying the senior adviser to the prime minister while keeping the prime minister constant. Appointing Rosenfield in place of Dominic Cummings while retaining Johnson does not appear to have appreciably reduced the sense of chaos, or greatly improved the culture.

The other experiment has been to keep Rosenfield constant while varying the people he works for. He was private secretary to Alistair Darling and George Osborne before working for Johnson. This variation has made a difference. The private offices of Darling and Osborne were never the subject of criticism for chaos or a culture of rule-breaking.

Taking these things together, doesn’t it seem the culture problem might be Johnson rather than Rosenfield?

Even if this were not the case, are we really saying that the people the prime minister appoints and is supposed to manage can behave exactly as they like? No 10 is a building. Until you put people in it, it doesn’t have a culture. And the people in the building all work for Johnson. If the culture is their responsibility, it is also his responsibility.

One of the arguments being used in the prime minister’s defence is that he is the victim of a vengeful campaign being run by Cummings. And such campaigns must be resisted. Even if this was a complete explanation for the stories (which I doubt), it still leaves this question: who employed Cummings?

I certainly didn’t give him the job of senior adviser. Nor did I advise the prime minister to employ him. And he didn’t just show up at No 10 on “bring your ruthless friend to work” day and decide to stick around. Johnson sought him out and gave him a job because of Cummings’s relentless focus and his determination that nobody would stand in the way of his objectives. And Johnson got what he paid for.

No 10 combines permanent civil servants and special advisers. Because the appointment of special advisers is more personal, it is right that ministers face more questions about their conduct. But it cannot surely be the case that ministers, and in particular the prime minister, carry no responsibility at all for civil servants.

Apart from anything else, the authority of employees in No 10 flows entirely from their relationship with the prime minister. The system can’t work if the prime minister’s private secretary is not regarded as an extension of the prime minister, speaking and acting on their authority.

If MPs decide that Johnson is only responsible for the candles he personally blew out, or the canapes he personally consumed, they will be making a mockery of the very idea of parliamentary accountability.

The Times

There was a time when they used to teach children about Thomas Dugdale in schools as if he was an important political figure. Pupils studying civics would be told about his resignation as a result of the Crichel Down affair, and the lesson in ministerial accountability it taught. Looking back, it all seems rather quaint.