Netflix hit by stream of libel lawsuits

From Making a Murderer to The Queen’s Gambit, Netflix is facing a torrent of lawsuits from the subjects of some of its most popular shows.

Netflix is facing a torrent of lawsuits from the subjects of some of its most popular documentaries.

There are the parents depicted in Operation Varsity Blues, a dramatised documentary about the 2019 American college admissions bribery scandal, who say the show amounts to the “ultimate destruction of their reputations”.

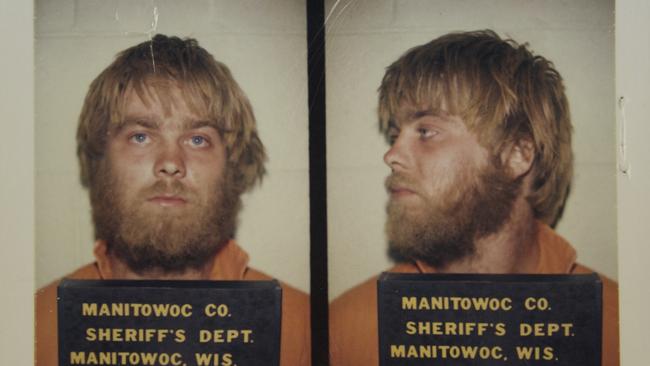

There is a Wisconsin police sergeant who says the 2015 true-crime documentary Making a Murderer, one of Netflix’s first runaway successes, insinuated that he planted evidence.

Then there is the chess grandmaster Nona Gaprindashvili, who claims Netflix was sexist in its portrayal of her in the chess drama The Queen’s Gambit, the former Manhattan prosecutor Linda Fairstein, who thinks it portrayed her as racist in When They See Us, a drama about a 1989 miscarriage of justice, and the Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, who is chasing Netflix for $80 million for his inclusion in Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich.

In all, The Hollywood Reporter says Netflix is facing more defamation complaints than any leading media outlet. It has not yet lost a case.

Legal issues began mounting after 2015 when, following the success of Making a Murderer, the streaming giant threw its weight behind true crime.

However, the cases raise questions about whether it can be held responsible for potentially defamatory documentaries or films that it “distributes” rather than makes. Even Netflix Originals, which are exclusive to the platform, usually involve other production companies. All the shows it has been sued for fall into that category.

Its lawyers have drawn comparisons between Netflix and cinemas, YouTube and bookshops, which do not historically end up in court over the content they exhibit or sell because of the “actual malice” standard, established by the Supreme Court in 1964, which makes defamation suits brought by public figures dependent on knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth.

“A distributor, such as Netflix, cannot be said to have disseminated a work of non-fiction created by someone else . . . with actual malice unless the work itself relates information that is on its face inherently improbable or there were obvious or [blatant] reasons to doubt the reliability of the creator,” its lawyer, Lee Levine, said at a 2019 hearing in its Making a Murderer libel lawsuit.

The judge, however, asked why Netflix, in that case, had accepted awards for writing and editing the show.

This suggests that Netflix will struggle to present itself as a distributor the more it looks like a studio. The platform, which has more than 210 million subscribers, won 44 Emmys this year.

Netflix has a trump card: section 230 of the US Communications Decency Act, which provides immunity for internet platforms with respect to third-party content. Yet it appears to have positioned itself rather as part of the film and TV industry, having left the Internet Association, one of Big Tech’s main lobbying groups, to join the Motion Picture Association.