My long night with Jordan Peterson — and his superfans

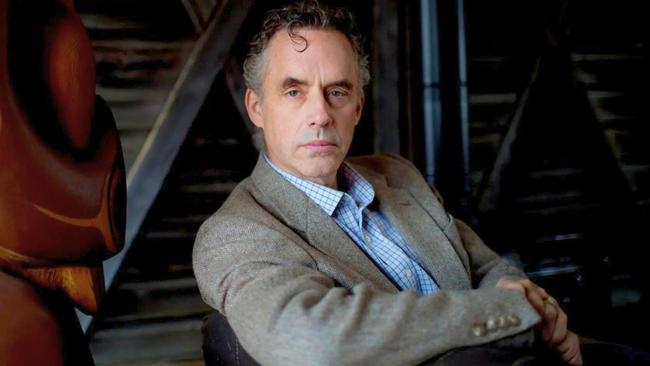

Peterson, 61, is the first philosopher to play the O2. The venue’s forthcoming acts include Take That, Olivia Rodrigo and Madonna. Only a decade ago, Peterson was a charismatic but little-known middle-aged psychology professor at Toronto University. Now he is – to use the obligatory formulation – “the world’s most famous public intellectual”. He owes that fame to his viral video lectures, which dispense stern, old-fashioned life advice to the young: stand up straight, tidy your room, take responsibility. He is also the right’s pre-eminent culture war icon. In perhaps his most famous video (recorded, ironically, by an enemy), Peterson emerges from a Toronto university building, an avenging patriarch in shirtsleeves and red braces, to debate pronouns with a crowd of angry left-wing student activists. He obliterates them. It is one of the canonical moments of the culture war.

The stereotype of Peterson is that he is a guru for lost (and possibly slightly alarming) young men. “How were the incels?” a friend cheerfully asked me the next day. But – with the exception of one angry, socially maladjusted-looking young man I spotted hunched in the audience next to his mother (I gave him a wide berth) – there weren’t many people in the audience who fitted the stereotype. The crowd was young, diverse and (to use an internet word) strikingly normie. There was little sense of an intense and furtive online fandom creeping out from underneath its fetid log into daylight. I canvassed most of the people I talked to for an estimate on the gender balance and the consensus seemed to be 60:40 male to female.

Most interesting was the audience’s class profile. With the exception of a few Oxbridge-looking student Tories strutting about the O2’s precincts with haircuts, blazers and blaring accents, it was not a posh crowd. All of the people I spoke to had attended a non-elite university or no university at all. Sartorially, many of Peterson’s fans were unexpectedly “Essex-y": glamorous girls with platinum blonde hair, big furry coats and high heels, clinging to their boyfriends in tight shirts and tighter trousers. It was an audience that felt far from the worlds of elite discourse in which Peterson is intellectual enemy No 1. A YouTube crowd, not a Twitter crowd.

A typical attendee was Lauren, 21, a cherubic Scottish student in a big pink scarf who enthused that Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life “completely changed my perspective on the whole world”. Though chiefly interested in Peterson as a psychologist, she was curious about his politics, which spoke to her concern about her university “letting trans women into women’s spaces”, an issue she thinks a lot of people agree with her on “but they’re scared to talk about it”.

Andrea, a recovering drug addict in electric blue trousers, referred to Peterson with affectionate irony as “Jordan” and told me that because “the world is a mess” she admired his ethic of “structure” and his opposition to a culture that encourages us to “be your own God”.

Another young man said that when he listens to Peterson, “I feel like it’s my dad speaking”. A common theme. Peterson’s fans love his ethic of order, tough love, self-reliance. Most people I spoke to agreed with everything Peterson said on politics but then (when I pushed them) hesitated to define themselves as right wing.

The atmosphere seemed good-natured but there must have been a whiff of paranoia in the air because when I left my satchel under my seat to go to the loo before the show, I returned to find that all the people sitting near me had reported it to the O2 security team as a potential bomb threat. “It doesn’t have a bomb in it,” I explained to a grim-faced official, “just Peter Brown’s The World of Late Antiquity.” I refrained from adding that you might consider his analysis of the later Roman Empire explosive.

Peterson’s warm-up act was a Cambridge PhD student called David Cotter, who played Ravel’s Bolero on an electric guitar to general audience indifference. More impressive was a thundering video promoting an organisation called ARC (the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship). Technically Peterson’s talk was the climax to ARC’s London conference but nobody in the audience seemed to know, care or understand what ARC was. Their video was watched appreciatively enough, however. Projected onto screens on either side of the stage, it featured expensive footage of churches and classical architecture interspersed with clips of assorted right-wing luminaries intoning uplifting banalities about the glories of western civilisation and the importance of community. Among them were the hedge fund billionaire Paul Marshall (who funds ARC, GB News and UnHerd) and his son, the former Mumford and Sons guitarist Winston Marshall. I wondered whether I was the only one who found the video slightly dystopian.

At last, to a great roar of enthusiasm and relief, Peterson appeared, dressed in a navy and maroon particoloured suit jacket and maroon trousers. A rank of military-looking banners behind him bore the abstract cover illustration of his philosophical magnum opus, Maps of Meaning, like a heraldic device. From my position, three rows from the front, he looked old. I could see the fine wrinkles around his eyes. He walked stiffly. His weird suit and haunted good looks gave him the air of an ageing conjurer or an HBO producer’s vision of an autocrat from the dystopian near future.

Somebody screamed: “We love you, Peterson!” And then he began to talk. He started slowly. A rambling, impenetrable anecdote about a chat he’d just had backstage with his friends that was going on way too long. What was he on about? Had he lost his edge? A couple of years ago, at the apogee of his fame, Peterson suffered a catastrophic mental breakdown. A benzodiazepine addiction led to anxiety, depression, pneumonia and even, one doctor thought, schizophrenia (Peterson insists he was misdiagnosed). The ailing philosopher was flown – nobody knows quite why – to a rehab facility on the outskirts of Moscow, where he was placed in a medically induced coma. He still seems to be recovering. Over the past couple of years he has wept so regularly in interviews that you can watch a YouTube video called “Jordan Peterson crying over and over again about the most mundane and odd things”. Was I watching a broken man?

But almost before that thought had formed I understood – the way you sometimes don’t quite notice exactly when a plane has left the ground – that we had already made oratorical takeoff. The sentences were coming faster. The ideas were more urgent. The themes more fluid. The runway was vanishing beneath us. Peterson isn’t one of those people who “speak in full paragraphs”. He speaks in one long paragraph that wanders about and doesn’t always make sense. It is, nevertheless, quite amazing to witness. On Wednesday night we got the misery of solipsism ("there isn’t any difference between thinking of yourself and being miserable"), the importance of marriage and family ("there’s nothing better you can have in your life than a wife who loves you unconditionally and children who think you walk on air") and the necessity of taking on responsibility ("are you shouldering enough responsibility?").

Uplifting small-c conservative life advice dressed up in grandiose philosophical mumbo jumbo is the heart of Peterson’s appeal. The crowd loved this stuff and the applause came more and more regularly. It sounded so reassuring that I sort of wish I believed it too. But, horrible cynic that I am, I couldn’t help but cringe when I was instructed to become “an individual willing to take responsibility for every level of being” or told that “everyone is a divine centre of intrinsic value”. The line between Jordan Peterson and Gwyneth Paltrow is thinner than is commonly recognised. I was reassured to notice that when Peterson began to wax philosophical – we all belong to a “chain of being” that leads up towards the “ultimate good” – the man next to me pulled out his phone and started absently scrolling through WhatsApp. Three hours is a long time for a talk.

More depressing to witness was the conspiracist turn Peterson’s thought has taken. He warned us in apocalyptic terms against “top-down, power-mongering, fear-wielding global utopians” who “offer a vision of the planet in which everyone has to pull back in terror of the impending apocalypse”. The idea seemed to be that the prospect of climate change is being used to cow and manipulate a supine population. “The tyranny that enveloped us during the Covid crisis is not that far away!” Peterson said, holding his finger and thumb together to show that tyranny is very close indeed. Doesn’t telling people there’s an evil cabal of tyrannical “global utopians” also count as fearmongering? I refrained from putting my hand up to ask.

Lockdown and its tyrannies was a big theme of the panel that formed the last phase of the show. I have hardly thought about lockdown since it ended. Peterson’s panellists – the journalist Douglas Murray, the YouTube-famous French-Canadian icon-carver Jonathan Pageau, and the climate sceptic Bjorn Lomborg – seem to have thought about little else. For me, the pandemic was a time when I stayed inside and played a lot of Scrabble. For them it was a bitter foretaste of a pseudo-utopian globalist nightmare.

The panel, frankly, was a bit of a mess. I have yawned through hundreds of these – four blokes chat about the challenges facing modern society – at a hundred provincial literary festivals. You can put a literary festival panel in the O2 arena but it does not fundamentally redeem the format. Peterson’s guests were understandably keen to show off in front of the massive audience. But their efforts to elbow into the spotlight were thwarted by Peterson, who turned out (perhaps not unsurprisingly) to be the panel chairman from hell, prone to asking rambling incoherent questions about the ultimate good or embarking on long incomprehensible speeches about the great chain of being. You wouldn’t get away with that at Hay-on-Wye.

An obviously flummoxed Pageau was instructed to explain the relationship between “individual responsibility” and “eternal social and theological order”. He will be having anxiety dreams about trying to explain his argument to an audience of almost 20,000 people for the rest of his life. Pageau managed something about how members of an atomised society could be controlled by “a massive global system”. I wondered uneasily how many of the nice-seeming people I’d met in the crowd were buying this.

Murray was the biggest hit with the crowd. He spoke in an extraordinarily languorous received pronunciation drawl and smiled to himself with an expression of almost deranged self-congratulation every time he made a point. I got the impression Murray was attempting to muscle in on Peterson’s self-help guru shtick as he kept fixing us with a look of infinite spiritual compassion and urging us “to look around you! Look up from your screen! Marvel! Be grateful for a moment!” Later he counselled gnomically: “What are the things we would be doing if we weren’t distracted by the things we are distracted by.” Eh? Oh well, the crowd loved it.

For the last 15 minutes another all-right hero, Ben Shapiro, was introduced as a special guest. A forest of phones went up as everybody tried to get a picture. But Peterson was too excited about Ultimate Meaning and Shapiro barely got a word in.

At last, after a final windy peroration from Peterson, the evening was over. All three hours of it. I walked into the cold North Greenwich rain feeling disturbed. It’s one thing to see all this stuff – global utopians, lockdown tyranny, threats to western civilisation – flying about the internet. To witness it in real life is depressing. Is this nonsense the future of our politics? The thought is almost too bleak to contemplate. I’m beginning to think I need some sort of motivational self-help guru to cheer me up.

The Times

“Is there an ultimate meaning to life?” Jordan Peterson cries. “Is there an ultimate good? Is there a God?” The famous voice – shrill, hoarse, reminiscent of Kermit the Frog – charges these abstract questions with an almost desperate urgency. Peterson is warmed up now, pacing the stage and talking with incredible fluency: God, western civilisation, marriage, sin, ultimate meaning. The audience at the O2, filled almost to its 20,000-seat capacity, interrupts regularly to applaud with the rapt unanimity of a North Korean Communist Party delegation. A friend seated right at the back of the arena texts: “This feels like a 19th-century religious revival meeting”. And it really does. It is one of the strangest nights of my life.