Musk is playing a dangerous game in Ukraine

The fragrance cannot smell any worse than Musk’s recent forays into geopolitics. First there was his Twitter plan for peace in Ukraine, which he invited tweeters to vote on. It involved Ukraine relinquishing its internationally recognised sovereignty over Crimea; UN-supervised elections in the four regions invaded and partially occupied by Russia and where the Ukrainians are on the offensive; and whoever wins those elections gets the territory.

The finest fragrance on Earth!https://t.co/ohjWxNX5ZCpic.twitter.com/0J1lmREOBS

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) October 11, 2022

Unsurprisingly the proposals were described as “very positive” by senior Kremlin officials and discussions took place on Russian talk shows about how Musk’s intervention might help Putin’s infowar over Ukraine. Since this bit of tweetomacy suggested the possibility of a weakening of western support for President Zelensky, Zelensky himself responded smartly with a Twitter poll of his own. And the Ukrainian ambassador in Berlin rebuffed the mega-billionaire using a word not usually deployed by diplomats. I should add, it was claimed this week Musk had revealed he had talked to Putin about his plan. Musk has denied this in strong terms.

Ukraine-Russia Peace:

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) October 3, 2022

- Redo elections of annexed regions under UN supervision. Russia leaves if that is will of the people.

- Crimea formally part of Russia, as it has been since 1783 (until Khrushchev’s mistake).

- Water supply to Crimea assured.

- Ukraine remains neutral.

Last Friday an interview with Musk in the Financial Times saw the tycoon extending his problem-solving to relations between Taiwan and China. “My recommendation,” he said, “would be to figure out a special administrative zone for Taiwan that is reasonably palatable . . . and I think probably that they could have an arrangement that’s more lenient than in Hong Kong.”

Well that’s comforting. Or would be if the same “more lenient” settlement hadn’t in fact been exactly what we thought had been agreed for Hong Kong. And we all know how that has worked out.

Which @elonmusk do you like more?

— Володимир ЗеленÑький (@ZelenskyyUa) October 3, 2022

Naturally, once again, the representatives of the autocratic regime talked up the Musk suggestion and the representatives of the threatened democracy denounced them. All this matters because, as Roger Boyes wrote in these pages this week, the Chinese calculation about their “recovery” of Taiwan has been thrown out of kilter by the robust response of Biden and the West over Ukraine. In other words, the appearance of western resolve may be a critical factor in deterring aggression. And that was what Musk seemed to be undermining.

In the case of China it is easy to imagine Musk pursuing his own self-interest when saying what Beijing wants to hear. His Tesla company has a huge operation in China, including a mega factory in Shanghai. In January it opened a showroom in the province of Xinjiang, where the local Uighur population has been subject to measures that amount to a slow genocide.

But his motivation could be something other than money. In Ukraine when the war started Musk supported Kyiv by using his Starlink systems to stop the Russians blocking Ukrainian communications. So it may well be that Musk genuinely believes it is his role to help bring peace to the world. And if you’re a megabillionaire sold on the idea of the importance of great men doing deals, then giving the autocrat some of what he wants (even if it belongs to someone else) may make a lot of sense. In the late 1930s the Anglo-Canadian newspaper tycoon Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) agitated to allow Hitler to annex pretty much anything in Europe he wanted in return for peace. Then, war declared, Beaverbrook became an energetic prosecutor of the conflict and instead discovered an admiration for Stalin.

Vladimir Putin has excited a degree of tumescence on the part of men who think they are also touched by the hand of history, from Nigel Farage and Alex Salmond in this country to Donald Trump in America. And there is the touch of Trump in all this: batting away the rights and sovereignty of the “small” person in pursuit of the Great Man’s objectives; the belief that the unique genius of the hugely wealthy is immediately and effortlessly transferable to politics and geopolitics.

It’s partly our collective fault. We indulge the unbelievably wealthy, perhaps hoping that some of their money-magic will overflow and slop on to us. We attribute to them wisdom they have often not shown and virtues they may not possess. You can watch a TED talk by Musk in which even his most banal comments are treated by the breathless audience as though they were the Ten Commandments as delivered by Chris Rock. It’s embarrassing.

Of course, megalomania can be partly redeemed by good works. But whereas, say, Bill and Melinda Gates’s philanthropy has saved billions of children from the ravages of polio by helping them to be vaccinated, Musk’s giving has been distinctly opaque. As Fortune magazine asked in February, “If a mega-billionaire donates 2.4pc of his fortune to charity but no charity gets any money, does it actually count as philanthropy?”

As the old adage has it, “handsome is as handsome does”. Our world shelters a fair number of impossibly wealthy people who, as a result of their wealth, are able to exercise significant unelected and sometimes unaccountable power. That’s just a truism. The money inequity in this hardly matters since such people can buy 99.9pc of us in an afternoon. In that sense we are almost all strangely equal.

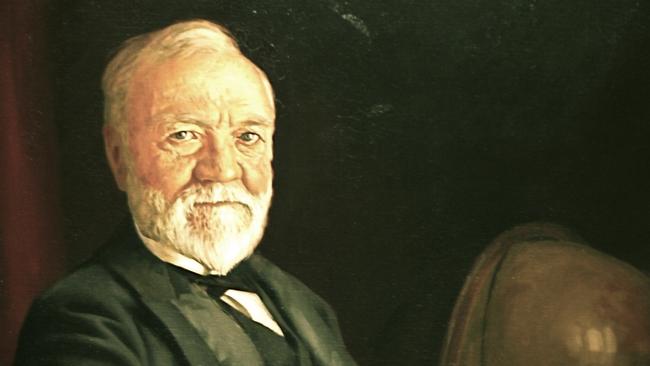

Power is another matter. The Scottish-American steel baron Andrew Carnegie was a hero when he endowed institutions of learning, but a villain when he indulged in monopolistic practices that had to be curtailed. At the height of the power of “robber barons” such as Carnegie, the great Democrat orator William Jennings Bryan delivered a Labour Day speech in Chicago. He recalled how, as a boy on a farm, they had put rings in the hogs’ noses, a source of discomfort to stop them rooting around and destroying property. He went on: “The thought came to me that one of the important duties of government is to put rings in the noses of hogs.”

As I contemplate the works of Elon Musk I begin to think we’re due a bit of nose-ringing.

The Times

For a hundred dollars, it was announced on Wednesday, you too can smell like Elon Musk. “The world’s richest man” took to Twitter (which he may soon own) to tell his tens of millions of followers that one of his companies had already sold 10,000 bottles of an “omnigender” scent called Burnt Hair. Expect a conspiracy theory to land in an inbox near you revealing how the Zionists are seeking to control us via our pheromones.