Modi’s dominance lays waste to once great party

The party that has dominated Indian politics for decades faces ruin.

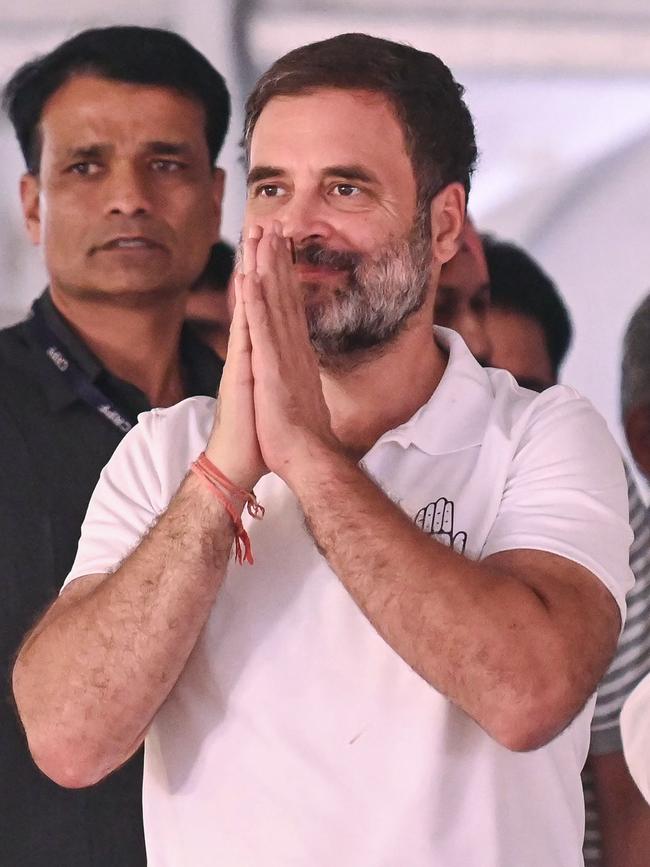

The crowds were swelling even before Rahul Gandhi took to the stage, seeking to rally support in the birthplace of his great-grandfather, the architect of Indian independence.

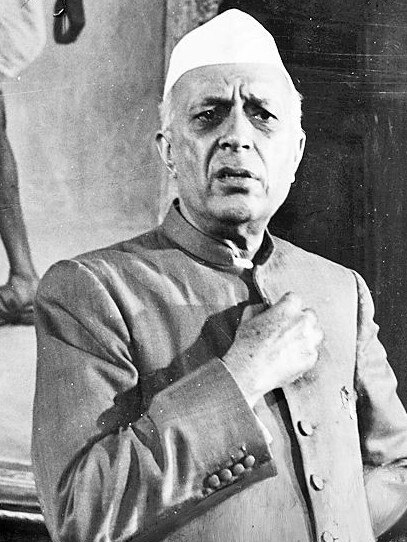

Allahabad, the ancestral home of Jawaharlal Nehru and the political dynasty he founded, has not come out in support of his Congress party in the decade since Narendra Modi shot to power in 2014, leaving the tainted, scandal-plagued “Grand Old Party” of India in ruins.

As Gandhi took to the stage with his regional ally in the critical state of Uttar Pradesh, the crowds surged forward, breaking the barricades and forcing Gandhi to leave without even addressing the crowd.

The debacle was something of a metaphor for Congress under Rahul Gandhi’s de facto leadership, struggling to overcome institutional disadvantages after a decade of Modi’s all-encompassing rule as well as in-built deficiencies of its own that have plagued it since the rule of his powerful grandmother, Indira Gandhi.

As Modi prepares to rule for a third term, aiming for a supermajority, Congress and the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty find themselves at a crossroads. Either the Modi wave is halted here, or the party faces near-certain extinction at a national level, ending a dominance that has lasted for almost six decades of independence.

India’s notoriously unreliable exit polls, released on Saturday night, pointed to an easy third term for Modi, though the range ran from a sizeable drop in support to a healthy majority with the support of allies. An aggregate of five put the BJP’s National Democratic Alliance at 365, just above its 2019 score but short of the supermajority threshold of 370.

Congress – formed by a British civil servant in 1885 as a “safety valve” against another nationalist uprising and ridden to freedom by the Indian independence movement in 1947 – became an open target for a resurgent BJP when it came to power in 2014 under Modi.

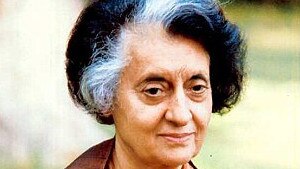

The fractures appeared under Indira Gandhi, Nehru’s daughter, who sidelined internal dissenting voices and instituted “high command control”, alienating grassroots workers. The

Emergency, a 21-month period from 1975 to 1977 in which the constitution was suspended, opponents were rounded up and atrocities were committed, was India’s darkest moment since independence.

Far from ending the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, though, Indira’s rule enshrined it. Returning to power in 1980 after three years in opposition, she launched a bloody crackdown on Sikh nationalists, including the massacre at the Golden Temple in Amritsar. She paid with her life, assassinated in revenge in 1984 by her Sikh bodyguards.

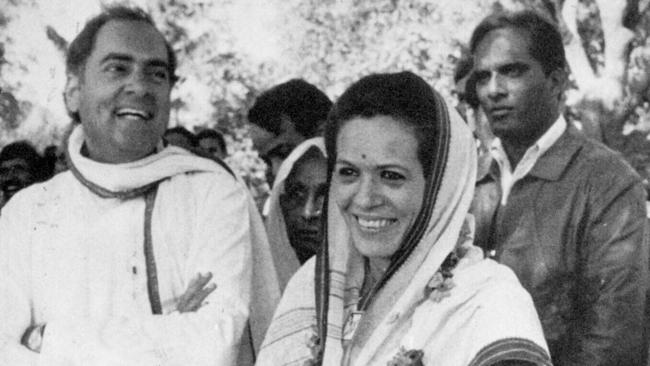

Indira’s son, Rajiv, took power on the day she was killed, having entered politics reluctantly at his mother’s behest after his younger brother, Sanjay, an MP, died in a plane crash. Rajiv was prime minister for five years and then leader of the opposition for a year but, six months after leaving office, he too was assassinated, leaving his Italian widow, Sonia, and their two children, Rahul and Priyanka.

Sonia declined Congress’s entreaties to lead the party, knowing her foreign birth was an issue and hoping to protect her children from the violence that had claimed their father and grandmother. Security threats made Rahul abandon his studies at Harvard, which he later completed at Cambridge, joining a management consulting group in London and subsequently in Mumbai.

Sonia agreed to lead the party in 1997 and Rahul entered politics in 2004, taking his mother’s seat in Amethi, Uttar Pradesh, while she moved to neighbouring Raebareli. After Congress’s shock 2004 victory over the first BJP government, Sonia declined to become prime minister, remaining party president while economist Manmohan Singh fronted the government.

Rahul was not a natural politician. “He is an introvert,” says Rajesh Pati Tripathi, a Congress veteran and scion of an Uttar Pradesh political dynasty founded by his grandfather, who became a freedom fighter against British rule at the age of 14.

“He’s not great at a rally. He doesn’t open up, which people think is arrogance.”

Rahul’s diffidence may be linked to the “cocooned and secure life” he grew up in as a consequence of his privilege and intense security fears, political analyst Dwaipayan Bhattacharyya says.

Rahul swiftly became an easy target for Modi’s mockery, an entitled young princeling in contrast to his self-made, low-caste persona. The BJP nicknamed him “Bappu”, a pejorative meaning variously “idiot” or “child”. Modi makes a virtue of his childlessness, which he contrasts with the dynastic politics of the opposition, accusing it of self-interest and nepotism.

In 2022, with Congress still cratering in the polls but Modi dented by a botched pandemic response, Rahul set out on a “yatra”, or march, along India’s vast length. The tagline was “Bharat Jodo” (unite India), a riposte to Modi’s divisive politics. It began on India’s southernmost tip in Tamil Nadu, opposition-friendly territory, and took Gandhi all the way to the Muslim-majority Kashmir, stripped of its autonomy by the Modi government in 2019.

The yatra “changed Rahul”, says Pratu Patel, a veteran communist leader in Allahabad and a friend of the Nehru-Gandhi family. Meeting ordinary Indians by day, sleeping in family homes or makeshift shelters by night and growing a long greying beard gave Gandhi the air of a sadhu, a holy person.

It was the bursting of his privileged cocoon that had the greatest effect, Tripathi says. “If you take a walk in the villages in a faraway place, it will change you,” he says. “When you don’t know the reality of what is really happening, you are within yourself. Once you start going there and start living with those people, you can never just be a ‘Delhi politician’ any more. He’s a changed person.”

But is it too late, with Modi poised for a third term?

Gandhi is no rhetorical match for Modi. His yatra may attract new young workers but the party faces a marathon rebuilding. Perhaps the strongest evidence of Gandhi’s new skills is the frequency with which Modi now targets him, not as Bappu but as “Shahzada”, meaning “emperor’s son”, an Urdu world intended to cast him as a Muslim in Hindu clothing.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout