May’s fatal Brexit errors

Theresa May made terrible blunders but she had several chances to save the day.

Theresa May’s tears when she announced on Friday that she would be standing down as Tory leader were not her first in recent weeks. The novelty was that they were public.

Those who worked closely with the British Prime Minister have seen the strain several times this year. After the second “meaningful vote” on her Brexit deal was defeated by 149 votes on March 12, May was visibly upset.

“That was the bleakest moment,’’ one of her aides said. “That was when she said to the staff that she didn’t think it was going to work out.” Hours earlier, Attorney-General Geoffrey Cox had refused to change his legal advice, killing any chance of winning over Eurosceptics and the Democratic Unionist Party.

Two weeks later, May was more angry than hurt when she announced to MPs that she was prepared to stand down if her deal passed — and still fell 58 votes short. “She was furious about that,” says one aide. “It was a case of: ‘What more do you want from me? I’ve done everything I can.’ She was upset but there was a much sharper edge to it.”

On Friday, as May walked back into No 10, her face an agonised mask, she was greeted with applause. In an address to advisers in the staterooms upstairs, the Prime Minister was emotional but defiant. “She said we had all done all we can,” said one of those present. May apologised for breaking down in the street as she concluded her speech: “I’m sorry.”

Her chief of staff, Gavin Barwell, said: “You have nothing to apologise for.”

The question haunting Downing Street staff and Tory MPs is just that: to what degree was May to blame for her own demise, or was it a result of impossible circumstances? In truth, it was a combination of the two: May’s introversion and lack of people skills greatly harmed her ability to play the hand she was dealt.

Of the four prime ministers I have covered as a journalist, May is the one with whom I have spent most time and perhaps understood the least.

On Wednesday night her aides railed that Andrea Leadsom had not given No 10 warning of her decision to resign from the cabinet. Leadsom had actually telephoned May half an hour earlier to explain her decision, and May had not felt the need to tell her team.

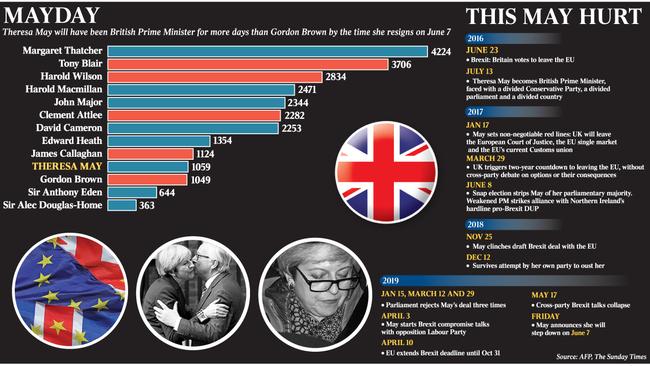

The verdict of ministers, aides and officials is that May made five disastrous strategic errors. The first was to box herself into constricting red lines in her first speeches on Brexit as Prime Minister. She then ignored the advice of officials and triggered article 50, the formal trigger for withdrawal from the EU, in March 2017 before she had a plan worked out.

May’s third mistake was then to call a general election in which her own performance contributed to a catastrophic loss of majority. After the exit poll that night, one of her closest aides said: “Well, that’s Brexit as we know it f..ked.”

If May understood that Brexit would now require a different approach, she did not level with either her MPs or the public.

Weakened and dispirited, she made her fourth mistake, meekly ordering her Brexit secretary David Davis to accept the EU’s sequencing of the talks, where Brussels refused to engage on a future deal until Britain had agreed to pay an exit bill in the tens of billions, settle the rights of EU citizens in Britain and keep open the Irish border. That decision led inexorably to acceptance, in December 2017, of the Northern Ireland “backstop”, the issue which vaporised support for her from Eurosceptics.

In an effort to reconcile the competing views in her own party, May’s fifth sin was to work secretively and behind the backs of key cabinet ministers on the deal she presented in July last year at the Chequers summit, which never commanded the support of either Brussels or the ERG group of Eurosceptic hardliners at home.

However, even after these cumulatively disastrous decisions, there were five moments where May might have saved the day but her caution ensured she failed.

Turning point 1: Failing to demand an exit from the backstop, last July

After the resignations of Davis and Boris Johnson, May’s new Brexit secretary Dominic Raab was dispatched to reopen negotiations with Brussels. Raab says that in his first talks with the EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, he made the case that Britain needed a way to leave the backstop. Barnier replied: “I understand that it needs to be short.”

Government lawyers drew up two proposals. May’s Brexit war cabinet agreed that Britain should demand option two, which would give it the unilateral right to leave the backstop.

But Raab says: “I was undermined by others in government. There was a huge opportunity there, but we were not robust or resolute enough.” In private, he has told friends this was a “sliding doors moment” when the course of Brexit changed.

May, who had lost her political consiglieri — Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill — after the general election, did not authorise her civil service negotiator Oliver Robbins even to demand a unilateral exit clause. “Olly, Barwell and David Lidington (May’s deputy) filled the vacuum after Nick and Fi left,” says one minister.

Turning point 2: Accepting the deal, November

When the deal was finalised last November, May’s aides say she had another chance to take a stand. The backstop still had no exit mechanism, and May had already reaped the benefits of a public display of truculence in September when she publicly berated the EU for its discourteous response to her proposals at the Salzburg summit of EU leaders.

“November was the crossroads where we took the wrong path,” recalls one aide. “That’s the point where we should have taken a stand and said: ‘I’m sorry, we can’t sign this.’ ” Again, May was talked out of radical action by Barwell and her principal private secretary, Peter Hill.

By refusing to fight, May further exhausted her now dwindling political capital. “We kept draining the goodwill. We never replenished by fighting for the things we said we were fighting for,” an adviser says. “Look at the uptick we got after Salzburg from just accusing them of being rude. Imagine how much we could have restored the stock if she had kicked over the table. We never took a stand. We just shuffled forward.”

But if May was at fault, so too were her ministers. “Cabinet was appallingly leaky but also supine,” says one official. “They grumbled a lot but they capitulated and they never said to her: ‘We will not let you do this.’ ”

Turning point 3: Cox’s legal advice sinks second meaningful vote, March 12 this year

The lack of trust from Eurosceptics meant 118 Tories rebelled against May’s deal in the first “meaningful vote” on January 15, where May lost by 230 votes, the worst defeat in modern history.

By the time she put the deal forward a second time, even hardliners such as Jacob Rees-Mogg were looking for reasons to back the government. Downing Street hoped that tweaks agreed with Brussels would allow Cox to change his legal advice on the backstop to give them cover. But the Attorney-General — valuing his legal reputation above political imperatives — spelt out in blunt terms that Britain had no legal way out of the backstop. “When he opened his mouth in cabinet, you could feel the room collapse,” says one of those present.

May should have squared Cox first, but his advice arrived cold at 5.30am, and allies of the PM remain bitter about the moment they see as the terminal point of her leadership. One of her team said that day: “Brexit is dead. It died today.”

“People were looking for a pretty flimsy ladder to climb down and Cox wouldn’t provide one,” a source says. “He seemed to be the only lawyer in the known universe who didn’t realise you’re paid to give the client what they want.”

Turning point 4: Failing to pursue no-deal, March 21

Some cabinet ministers think a last opportunity to put pressure on Brussels was lost between the second and third meaningful votes. A group of ministers who had voted Remain but now supported Leave sought to persuade May to go full bore for a no-deal Brexit to put the jeopardy back on the EU27.

“We were hearing that the Germans might concede a five- or seven-year sunset clause on the backstop,’’ one minister says. “A group of us thought we had persuaded her. My understanding is that she went in on the morning of March 21 ready to go for no deal and was then talked out of it by Barwell, Lidington and Robbins. That was the last chance.”

To all these ministers she stayed an enigma who was not embarrassed by silence in meetings that others found socially mortifying. “It’s like trying to outstare a cat,” says a source fond of May. “It just doesn’t work.” One of her most senior aides told colleagues: “I know every single cabinet minister better than I know her.”

Turning point 5: Refusing to make Labour a bold-enough offer, March-May

A week later May suffered her third defeat and abandoned hope of passing her deal with Tory and DUP votes, instead opening cross-party talks with Labour.

For seven weeks the two sides talked, but May refused to give Labour what it wanted — a permanent Customs union with the EU — for fear it would not just split her party but destroy it.

“She didn’t want to be Ramsay MacDonald,” says one MP close to the leadership, a reference to the Labour prime minister who formed a national government in 1931 and was denounced thereafter as a traitor to his cause.

May played what she knew would be her final card on Tuesday, when she suggested to her cabinet that they could offer a free vote on a new referendum to secure Labour support.

Tory chairman Brandon Lewis led opposition to the plan, saying “the party would go apoplectic and rightly so”.

That left her with little choice but to publish a withdrawal bill that was far too cautious for Labour and far too radical for her own side.

“When we started, we were fighting EU intransigence,” says one aide. “By the end, we were too busy dealing with friendly fire.”

By 3pm on Wednesday most ministers had read the withdrawal bill. “Every one who had read it made it clear they could not support it,” a No 10 source said. By 5pm May had decided to resign, a decision she communicated to Sir Graham Brady, chairman of the backbench 1922 committee and — it is believed — to the Queen in her regular Wednesday evening audience at Buckingham Palace.

As the vultures circled, one senior figure in government remarked: “There is now an inner circle of one. It’s only (her husband) Philip in there with her.” Perhaps it was always that way.

May’s supporters say that since the general election political reality was stacked against her. “This task might just be impossible,” one says. “The numbers don’t work. A new leader will have a fresh bank of goodwill but that doesn’t change the mathematical reality.”

But in the final analysis, May both created that mathematical reality and lacked the skills to transcend it.

One old Westminster hand compared her to the least successful England football manager of recent times. “As Steve McClaren proved, it is possible to do an impossible job badly. And she did.”

The Sunday Times