Like Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro has been harmed by Brazil violence

It may have looked like chaos, but the rioters in Brasilia, or those directing them, knew what they were doing.

It may have looked like chaos, but the rioters in Brasilia, or those directing them, knew what they were doing. The three exquisite modernist buildings they stormed on Sunday in the heart of the capital were not random symbols of government but pillars of the country’s democracy.

The executive power is housed in the Planalto presidential palace, the judiciary in the Supreme Court, and the legislature in the space-age, twin-sphered congress building.

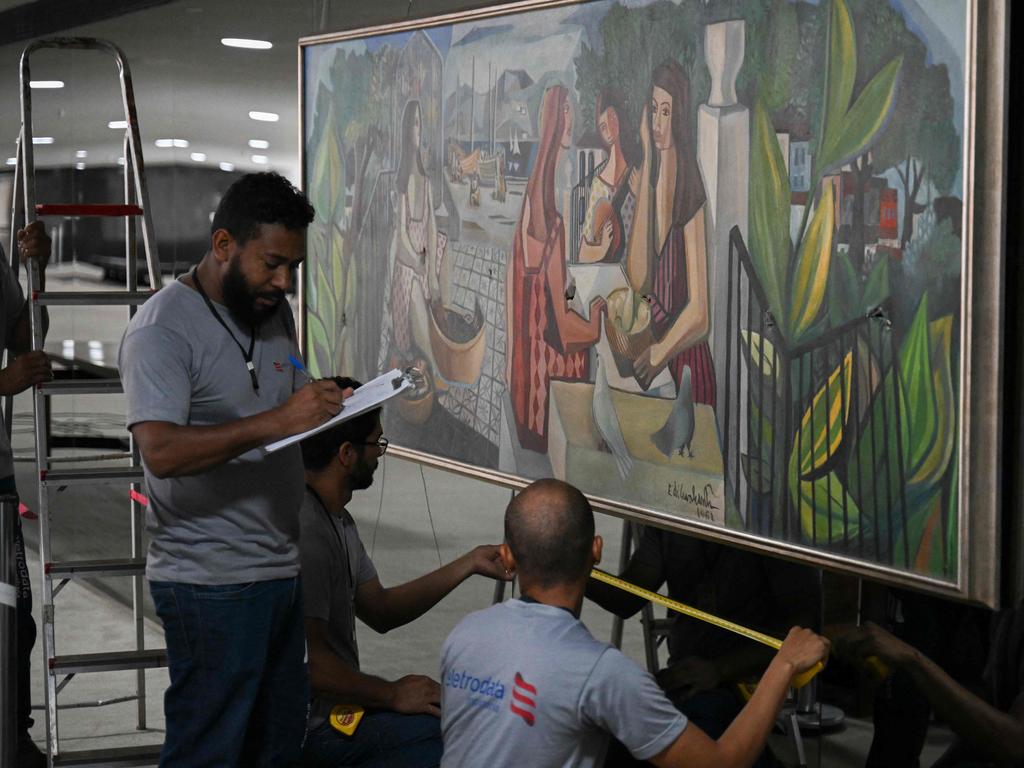

All were vandalised. As the clear-up began, it was obvious that amid the smashed glass and broken furniture, the material damage the mob wreaked was significant. But what of Brazilian democracy? Or the country’s recently inaugurated President, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva?

Is he now looking vulnerable to those anti-democratic forces, wrapped in the national flag, who showed their enraged faces on the lawns of the capital? Could Jair Bolsonaro stage a comeback? Will Brazil’s democratic institutions survive the onslaught?

Such talk is not outlandish in Brazil given that in 1964 a democratic government was ousted by a military dictatorship, which survived until 1985. But the 1964 coup took place under very different circumstances to those in which the country finds itself today.

The Cold War was in full swing, Brazil was paralysed by strikes. The left-wing president, Joao Goulart, was deeply unpopular. The idea that the military should depose him was supported by the media, the church, much of the middle class and, crucially, the US.

Lula faced nothing of the sort, and the fact that the riot was suppressed quickly has led many to conclude that he is safely in control.

The President, with support from all sides of congress, swiftly enacted a decree that placed Brasilia under federal control for the rest of this month. The army moved to clear an encampment of Bolsonaro supporters from outside a military base. The same soldiers, who protesters dared to believe would join them in overthrowing the government, were clearly following orders from their commander-in-chief, the President.

One view is that Lula will be empowered, not weakened, by the attack.

“In no way does this represent something which will lead to a coup,” Thiago de Aragoa, a political analyst based in Brasilia, said.

“In fact, when protesters become criminals, that makes life easier for Lula. He can use force and the law against them.”

De Aragoa said the consensus he picked up from many congressmen and women who were not supporters of Lula was that the scenes were “disgraceful” and would be deeply damaging to the wing of the opposition that sees its figurehead as the brooding former president.

“This was a disaster for Bolsonaro,” said Brian Winter, editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly.

“Given his self-imposed exile in Florida, and relative silence since losing the election, the race to succeed him as the leader of Brazil’s conservative movement will now gain even more momentum. Just as January 6 accelerated Trump’s decline, we are seeing opposition figures distance themselves from the former president.”

But some see warning signs. There has been some evidence of a possible fifth column in the midst of the security infrastructure designed to protect the government.

Brazilian media published photographs of police officers jovially talking to protesters while the storming of the public building was taking place in plain sight.

Supreme Court justice Alexandre de Moraes has suggested that the head of security for Brasilia, who was dismissed on Sunday, had “connived” with the protesters.

Surveys taken before October’s election, which Lula won by less than two percentage points, showed significant support for Bolsonaro among the police.

Millions still see Lula as tainted by the corruption allegations that led to him serving jail time from 2018 to 2019, even though all his convictions were later annulled.

“There is a silent minority that did not protest in the streets but still remain suspicious of the electoral results and the legitimacy of Lula in power,” said Guilherme Casaroes, political scientist at the Fundacao Getulio Vargas University.

Lula, he warned, should not feel completely comfortable yet.

The Times