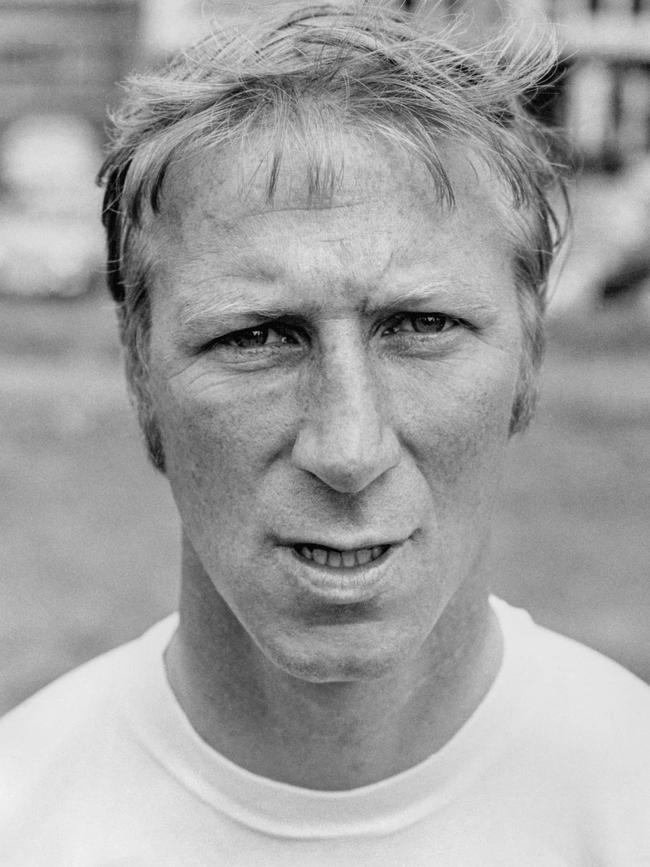

Lessons from Jack Charlton: Money changes sport for better, not worse

It was a decision that didn’t survive his first proper shift underground. He crawled on his hands and knees to the seam, experienced the blast as explosives blew out the coal, and then found he couldn’t see his hands for the dust. When he realised this would be his life eight hours a day, five and a half days a week, he decided Leeds United had its attractions after all.

And thus begun one of the truly great — and perhaps the greatest — football careers of any Englishman of the 20th century.

In the week of his death, events seem to add lustre to his memory. What a contrast his straightforward style provides to the tawdry financial shenanigans of modern football. And what better example could there be than the decision, announced on Monday, that Sheikh-owned Manchester City will not face serious punishment for what seemed to be obvious breaches of football’s financial rules.

Journey from shambolic amateur sport

Yet the more one studies Jack Charlton’s life, the more one questions this verdict. In fact, his true greatness lay in the steps he took from the shambolic amateur nature of the sport he joined to the extraordinary professional spectacle it is today.

This story of progress isn’t unique to football, by the way. It’s the story of many other sports but also of our country more generally. For all the defects of big-money sport, and indeed big-money capitalism, the journey of the last century has been towards the light.

Joining Leeds at the age of 15 did not involve the club in careful nurturing of precocious talent. Instead it involved a little training and many more hours of cleaning lavatories, oiling turnstiles, restudying boots and inflating balls. Then, shortly after Charlton finally appeared for the first team (an event that arrived by surprise, without any words from the manager and with no advice about what he was supposed to do) he was sent away for two years of national service.

As Charlton said about that experience (which, to be fair, he remembered fondly): “I learned all my bad habits in the army, and smoking was one of them.” He carried on smoking for the rest of his professional career.

Never mind allowing players to smoke, Leeds in the second half of the 1950s didn’t talk to their players much at all. They didn’t employ a coach. They didn’t practise corners or free kicks, they didn’t really have team talks or a run-down of the opposition line-up.

Meanwhile, players with young families needed to do other things to make ends meet. As an England international on his way to winning the World Cup in 1966, Jack was selling cloth to his fellow England stars from the boot of his car. Later he set up a souvenir stall outside the Leeds ground and his wife sold scarfs to fans.

The allocation of tasks in football was extraordinary. In his first managerial job, as the boss of Middlesbrough, one of the world’s greatest football strategists spent his time buying paint for the stadium gates and personally delivering fixture sheets to local offices and factories to be placed in their canteens.

All this may have romantic appeal but contrast it with the modern game with the way that talent is nurtured, fitness is honed, pitches are tended, players are scouted, tactics are developed, data is used; with the way that players are guided and supported, helped to plan their careers, allowed to concentrate on the game. Even with the way souvenirs are sold.

The sporting advantages of the big money that has come into the game are obvious. The cash has brought professionalism and that in turn has brought better sport. Football is faster, more skilful, better officiated, more (not less) sporting and played in better stadiums on better pitches. A young Jack Charlton would now be seen as an asset and businesses look after their assets.

Big money equals big advances

You can see the same trend in other sports. Tennis, for example. Elite players are now fitter, the game has become more powerful, rackets have evolved, and the median age of the top 50 tennis players keeps rising as the investment in physical strength pays off. And as the financial impact of bad calls increases, technology has developed to improve umpiring.

So, yes, the way money is raised and spent in some Premier League football clubs is a matter of concern. And yes, if you set rules you have to police them properly and the football authorities seem pretty hopeless at it. But the big money that has gone into the game has been far more positive than negative.

And, in any case, if you wanted to stop it, every sport would have to participate, which is hardly likely. Take the salary caps in rugby that led to Saracens having a huge points deduction for violations. If a young person capable of an elite professional career can choose any sport, why would they choose one with a capped salary? The evidence is that they would gamble on their talent.

Or take the Olympics. One of the great moments in the modern Games was the 1992 victory by the US basketball team that included the mega-salaried Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson. It was also the moment when it became plain to all that you could either have highly paid professionals who were the very best or amateurs who weren’t.

Jack Charlton should be remembered not as an icon of old-school football but as one of the game’s great pioneers. A champion of managers who were properly trained themselves and trained their players. A student of the game and of his opponents who developed novel playing techniques that became standard in the game and formations that often took rivals years to decode. And someone who cared about the business of the clubs he managed.

There’s a great tendency to believe the past was always better but Jack Charlton wasn’t like that. He was, for instance, fiercely loyal to the mining communities where he had such a happy childhood. And when the time came he was a friend and supporter of Arthur Scargill during the 1984-85 miners’ strike.

Yet ten years later he wrote this: “If you were to talk to some of them now, they would tell you that the closing of the mines was the best thing that ever happened to them. They have found a new lifestyle, and, more importantly, new hope.” Forward, always forward — that was Jack Charlton.

The Times

When Leeds United first approached Jack Charlton for a trial, he didn’t want to know. He was enjoying his life in the pit village of Ashington. He thought he’d stay there, fish a little, hunt rabbits and follow his father into the mines.