Leonardo DiCaprio at 50: Oscars, supermodels and saving the Earth

The child star who became a global pin-up has finally managed to grow up as a leading man. Off-screen? It’s still a work in progress.

Leonardo DiCaprio has always had an age problem. The Oscar-winning actor (for the 2015 film The Revenant), who turned 50 on November 11, has spent the lion’s share of his screen career wrestling with perceptions of his seemingly permanent adolescence.

He’s a former child actor who played boys and teenagers well into his 20s. He became frozen in the aspic of global celebrity as the fresh-faced Jack Dawson in the mega-smash Titanic (cue worldwide Leomania).

And when he attempted to transition into grown-up roles in his 30s it somehow didn’t seem real. On marking DiCaprio’s Oscar nomination for Blood Diamond in 2007, for instance, the great film critic Philip French noted that DiCaprio, who was then 32, was a “superb actor who hasn’t yet quite become an adult”.

His off-screen antics didn’t help. DiCaprio frequently was described as a “party boy” who liked to go on all-night benders with entourages 20-strong, rack up eye-watering bar bills and, according to a notorious New York Magazine profile from 1998, “chase girls, pick fights and not tip the waitress”. DiCaprio’s squad at the time was dubbed “the pussy posse” for reasons, alas, not at all associated with cats.

It set the template for the years to come, where “chasing girls” would evolve into a regular pattern of paramours who were invariably models (Gisele Bundchen, Bar Refaeli, Camila Morrone and so on) and usually 25 or younger, even as DiCaprio happily soared towards his sixth decade. He’s pushing the romantic envelope, though, by dating Italian model Vittoria Ceretti, who is, er, 26 years young.

This dating pattern is jokingly called Leo’s Law (no girlfriends over 25, even as you get older), yet it touches on something quite profound and very Dorian Gray in the DiCaprio narrative. It’s as if there’s an attic somewhere full of middle-aged models and actors who are in fact DiCaprio’s peers (Christy Turlington, say, or Olivia Colman) while he swans about in a 20-something dating pool that speaks directly to a personal mythology that was forged in the smithy of late-1990s stardom.

Everything, in short, changed with Titanic, when the star was 21. DiCaprio has spoken before about the blinding media glare that came with James Cameron’s apex blockbuster, saying he had no connection to “that whole Titanic phenomenon and what my face became around the world”.

Before that he had been “his generation’s great acting promise” (according to the San Francisco Chronicle) who had been nominated for an Oscar at 19 for What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, and had been hand-picked by Robert De Niro to star opposite him in the coming-of-age drama This Boy’s Life.

It’s easy to underestimate the impact of This Boy’s Life on the legacy of Leo. It’s a two-hander, adapted from a novel by Tobias Wolff and stars the inevitably “boyish” DiCaprio (17 during filming) as an alienated teen who frequently clashes with his mother’s new, fastidious and increasingly violent boyfriend, Dwight, played by De Niro.

There is a certain charge in the exchanges between De Niro and DiCaprio. It’s a thrilling, baton-passing quality that’s reminiscent of Marlon Brando handing over the keys of the Method kingdom to Al Pacino during The Godfather. That DiCaprio will eventually overtake De Niro as Martin Scorsese’s favourite muse somehow makes the film even more poignant.

This Boy’s Life, however, also established a template that recurred in DiCaprio’s career, that of working with a screen hero or older Tinseltown legend only to be wholly overshadowed by them.

DiCaprio’s first big splash for Scorsese, for instance, was in Gangs of New York, where he was roundly eclipsed by the mesmerising turn of his co-star Daniel Day-Lewis.

Later, in Scorsese’s The Departed, DiCaprio piled on almost 7kg of muscle and created a character of searing intensity, only to be outdone by the louche theatrics of his co-star and idol Jack Nicholson. The pattern seemed to reinforce the idea that DiCaprio had not yet reached maturity and was being surpassed by the grown-ups in the room.

But, yes, back to Titanic. DiCaprio wasn’t even supposed to do that film. He was circling Boogie Nights instead and was director Paul Thomas Anderson’s original choice for the lead. Just let that sink in. Boogie Nights with DiCaprio as Dirk Diggler, the role eventually made famous by Mark Wahlberg? And no Titanic? It would have altered the course of his professional life and beyond.

“I’m not saying I would have,” DiCaprio told GQ when discussing why he “wished” he had done the film instead of Titanic. “But it would have been a different direction, career-wise.”

The direction Titanic sent him was mostly into the hearts of young women and screaming girls, which often seemed to provoke the ire of young men and overprotective fathers. Senator John McCain, when referring to his daughter’s obsession with DiCaprio, famously called the actor “an androgynous wimp”.

It’s hardly surprising, then, that DiCaprio seemed to spend the entire midsection of his career (at least until his late 30s) attempting to prove he wasn’t just a pretty face, or indeed a pretty boy. This was sometimes unsuccessful, if not borderline farcical. In The Aviator, for instance, he hid poorly underneath a glued-on beard and old-man make-up as disturbed, late-era Howard Hughes.

Off-screen he was becoming an environmental heavy hitter, establishing the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation and backing a plethora of eco-activist projects and documentaries including the film The 11th Hour and the series Greensburg.

In 2014 UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon appointed DiCaprio a UN messenger of peace with a focus on climate change. In 2016 Time magazine included him in its list of “100 most influential people in the world”. He made some canny business decisions, including taking a pay cut to star in Inception while negotiating a share of the film’s ultimately enormous box office.

This allegedly resulted in him earning $US50m for that movie alone. It may explain his not especially voracious appetite for screen roles, preferring instead to bash out a prestige picture every two or three years, and instead get papped while holidaying on yachts in the south of France next to, naturally, some models.

His record as a serious Hollywood player is patchy. When he gets producer credits on his titles he generally hits paydirt. But the projects with other actors that he backs are often painful flops – see Ben Affleck’s Live by Night and Runner Runner, or Taron Egerton’s Robin Hood.

Back on screen, in the interim, DiCaprio was discovering his true metier as a performer. He began to excel in roles that required acting, or at least the foregrounding of the process. In The Departed his cop character Billy Costigan was “playing at” being a mobster. In Shutter Island his Teddy Daniels is deluded and pretending to himself that he’s a serving US marshal.

In The Great Gatsby DiCaprio’s title character is all front, all charade, acting like the millionaire he thinks we want to see. It’s as if DiCaprio is so saturated in his celebrity, or status as a global figure, that the only way it makes sense is to acknowledge the performer behind the performance.

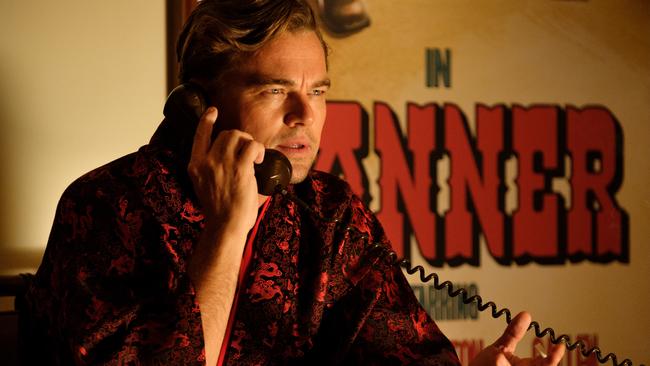

This process eventually reached its apogee in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. In the most extraordinary sequence of the film, perhaps of his career, DiCaprio’s fading movie star character Rick Dalton plays the villain on a low-budget western TV series, Lancer.

The scene is a hackneyed saloon stand-off, yet DiCaprio plays it with such expressive gusto that he veers, in the space of a single monologue, from camp to crazed to complex profundity. Once “cut!” is yelled, his preteen co-star Trudi Frazer (Julia Butters) whispers earnestly into his ear: “That was the best acting I’ve ever seen in my whole life!”

Dalton’s eyes fill with tears and we know as an audience that Trudi is speaking the truth and that DiCaprio has transformed before us into something genuinely exquisite. He was rightfully Oscar-nominated for the role but was beaten by Joaquin Phoenix for his (slightly gimmicky, it now seems) turn in Joker.

Since then there has been the environmental comedy Don’t Look Up and another Scorsese collaboration, Killers of the Flower Moon. In these DiCaprio has been fabulously shifty, nerdy and, in Killers, downright repellent.

As he segues into his 50s, in other words, he is becoming the epitome of an ambitious and nuanced character actor who has already made way for a new generation of pretty young things (see Timothee Chalamet).

And still, perhaps the greatest sign of DiCaprio’s evolution has yet to come, with his next movie. This one’s a crime film called The Battle of Baktan Cross and it marks his first creative collaboration with his “almost” Boogie Nights director, Anderson.

There is sweet circularity here. Nearly 30 years later, that wished-for “what if” Boogie Nights-inspired career can finally find expression in DiCaprio.

And, in his own way, as he celebrates his half-century, he can put the legend of the Leomania poster boy to bed and announce: “Behold the man!” And so, yes, his “age problem” is definitely behind him these days.

Now, if only he could move on from those models.

The Times