Kremlin reshuffle sets Vladimir Putin up for long Ukraine war

A more useful guide than Sophocles, I reckon, is Harold Pinter, the master of the comedy of menace.

Certainly there have been some long, Pinteresque silences from the Russian leader since his once loyal chef Yevgeny Prigozhin led a brief, aborted mutiny against the Kremlin last June. That began with foul-mouthed, video-clipped threats by the mercenary leader denouncing the defence minister Sergei Shoigu for neglecting the Wagner group.

Prigozhin was blown up in his plane, while Shoigu survived politically. But Prigozhin’s critique of army corruption lingered in the Kremlin; silence was ordained until Putin was “re-elected” president for a fifth term. The army’s budget has been ballooning but results have been meagre. Russia is advancing in eastern Ukraine, but slowly and at high cost.

By kicking Shoigu upstairs and replacing him with Andrei Belousov, who is better equipped to align Russian defence spending with a long attritional war, Putin has paid a kind of posthumous debt to the head of the Wagner group while also respecting the loyalty of his old hunting buddy, who now gets to be a yes man on the presidential security council.

The reshuffle appears to be rational – even, given Putin’s limited emotional range, considerate. Nikolai Patrushev, a former director of the FSB security service, vacates his position as conspirator-in-chief in the security council and gets to be a presidential aide instead, with plenty of face time with the boss.

That doesn’t exactly amount to a night of the long knives. Indeed, by the standards of the Kremlin court – the hushed-up corruption, the occasional defenestration – it is almost a cosy transition.

What is significant is the timing: it suggests that Putin is entering one of his periodic bouts of paranoia. The sense of Western encirclement is back.

In Georgia, as he sees it, the European Union is stirring up street protests against a government in the thrall of a Moscow-linked oligarch. It is beginning to resemble Kyiv in 2014 and, since a limited invasion in 2008, Russian troops have been occupying about 20 per cent of Georgian territory.

And then there’s a feeling of unease in the Kremlin about the imminent arrival in Ukraine of long-promised Western weaponry and how it will be deployed. The early condition, that donated weapons should not be used to strike inside Russian territory, no longer seems to be so binding.

If Russia fires on Ukraine from across the border then it seems legitimate for the Ukrainians to hit the firing positions. That has been the conviction in Kyiv all along; but western fears of an escalation became an excuse to slow down arms deliveries.

Now the Western inhibitions are less pronounced. That was the reason why British and French ambassadors to Moscow were summoned recently. Russia has been hinting increasingly at the possible deployment of tactical nuclear weapons.

NATO, meanwhile, is poised to invite Ukraine to start accession talks at its Washington summit in July. Can this be done while a country is actively engaged in a war?

Anders Fogh Rasmussen, the former NATO chief, certainly thinks so: “If you argue that you can’t extend an invitation to Ukraine as long as a war is going on, then you give Putin an incentive to continue the war to prevent Ukraine joining the alliance.” In other words: get on with it.

So Putin is impatient and anxious. He has entered his fifth presidential term, overtaking Joseph Stalin’s tenure in the Kremlin, and he knows that it is a moment of high vulnerability. Russia has become a war society, its triple-shift arms factories have become a feature of its expanding war economy, more than half a million men are currently fighting for Russia in Ukraine.

Belousov, Putin’s appointment as defence minister, has never served in the army but his task is to secure the manpower needs and production capacity for a long war, creating military innovation hubs while at the same time ensuring that the civilian and consumer economy doesn’t crumple. He’s a new blend of technocrat and securocrat, not the kind of grizzled old KGB hand that tends to hang out with Putin.

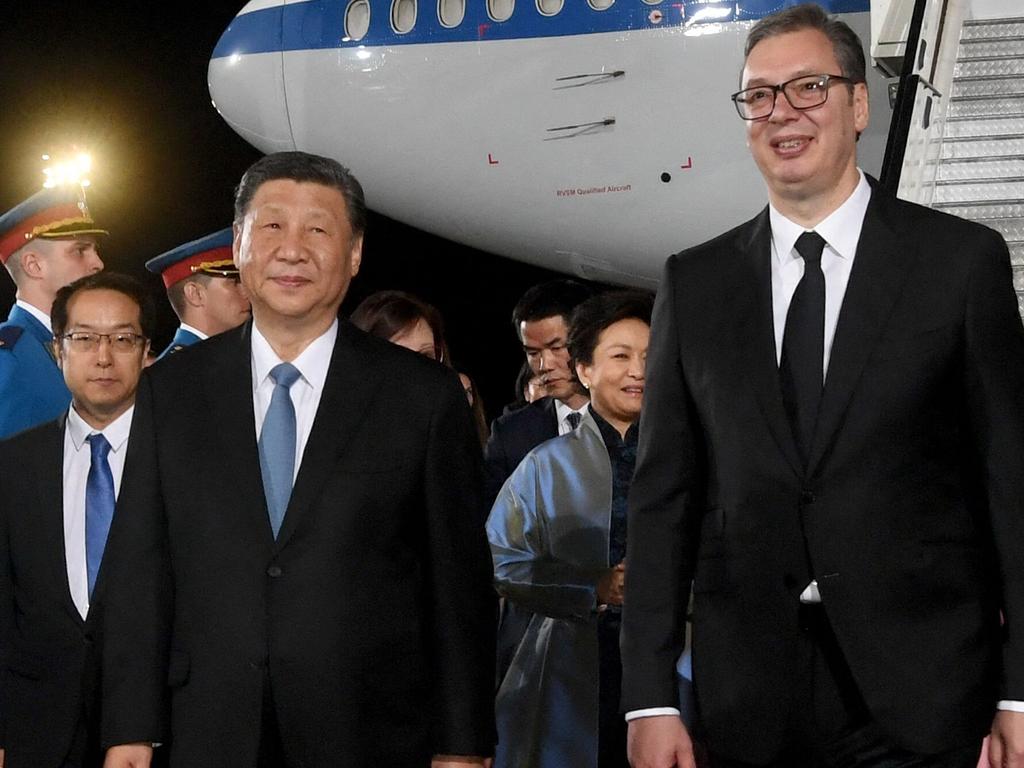

Belousov, crucially, has a web of contacts with the Chinese leadership. At current rates of expenditure, Putin has about another 18 to 24 months left to bring his war to a “successful” conclusion. Anything longer could stretch the patience of China and would create serious social and economic tensions inside Russia (the dislocated education system, the mental health problems, the crime rate).

Long wars have long tails. It would certainly focus minds on the Putin succession. That goes some way to explaining why Patrushev (who is, like Putin, in his early seventies) has been appointed a “presidential aide”.

Putin needs eyes and ears on the secret police who would be pivotal in a forced or accelerated succession. He wants someone around who shares his world view. Patrushev is notably anti-American – after Putin’s first inauguration, in 2000, they saw a patriotic action movie, Brat 2, together and apparently still roll out zinger quotes ("Tell me, American, what is power?").

Some suggest that Patrushev’s son Dmitry, currently minister of agriculture, could be in the running for high office, perhaps even a contender for the Putin succession. But if the past quarter of a century has taught Russians anything, it is keep your ambitions under wraps and your windows shut.

The Times

More Coverage

There is a Western tendency to see Vladimir Putin’s leadership as mimicking a classical Greek tragedy, full of Athenian power play peopled by flawed, arrogant heroes and dependent on flashes of divine intervention. This unduly flatters the Kremlin.