Joe Biden to sweet-talk Pacific Islands in battle with China

Remote and overlooked ocean states now find themselves the centre of attention.

Even two years ago, the presence of the leaders of Kiribati, Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia would have been a matter of cool indifference to almost everyone in the United States.

The three are members of the group known as the Pacific Island nations, among the remotest, poorest and, to the powerful countries of the West, the most insignificant countries in the world.

For years these dots on the map have been literally sinking into the ocean because of rising sea levels to the indifference of the West, but this week Pacific leaders will gather in Washington to be showered with hospitality by President Joe Biden himself.

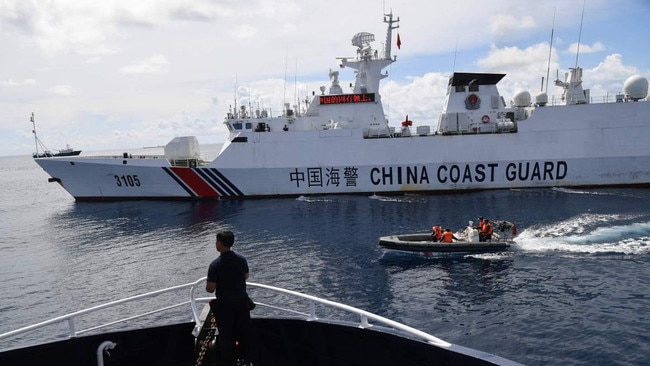

For the second time in a year governments including Polynesia, Fiji and Papua New Guinea will meet for the US-Pacific Islands Forum Summit. Biden will announce new funds for undersea data cables, action against illegal fishing and US diplomatic recognition for the Cook Islands (population 17,000) and Niue (population 1700).

He will entertain the visiting leaders at the White House and take them to an American Football game. The Pacific nations are suddenly small players in a big game of their own: the struggle for military power and economic influence between the US and China.

The human population of the 14 countries of the South Pacific is less than 13 million but their scattered islands cover 15 per cent of the surface of the planet. During the World War II bloody battles were fought between Japan and the US in the Solomon Islands and Palau for control of their air strips and harbours. In any conflict between China and the US they would have similar importance.

Having constructed military bases in the South China Sea and threatened the self-ruling island of Taiwan with invasion, China has begun extending its tentacles into the South Pacific.

Much of this has been in the form of aid, investment and construction by Beijing and its state-owned companies, which have been building roads, clinics, schools and stadiums across the region from Vanuatu to Kiribati.

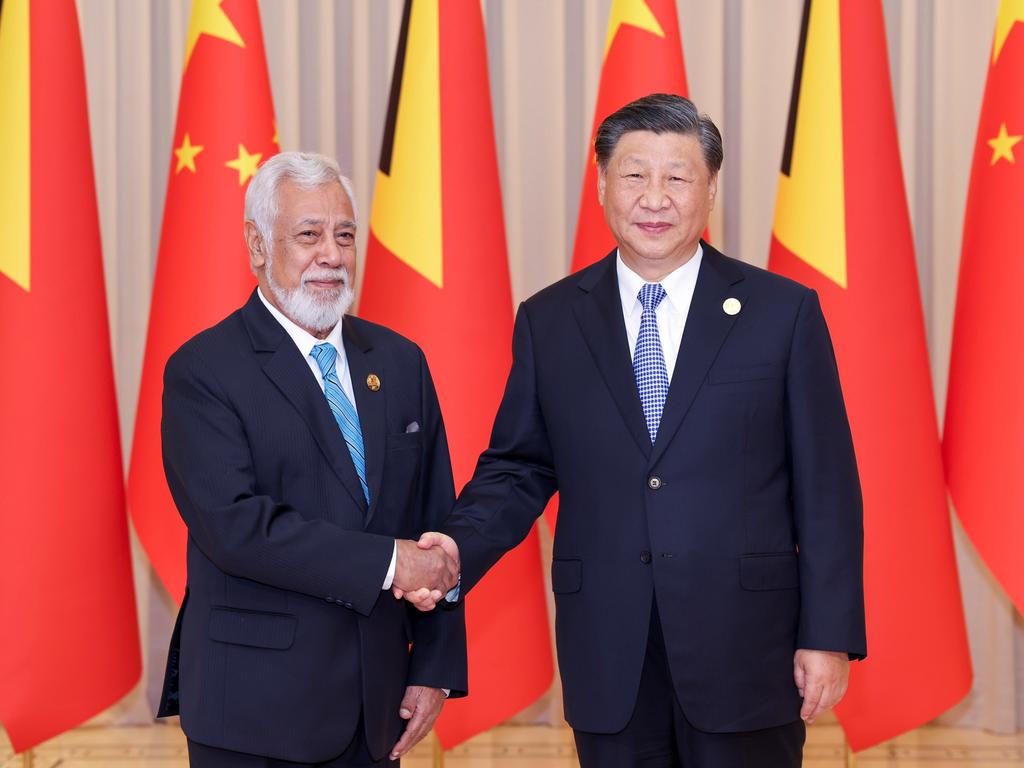

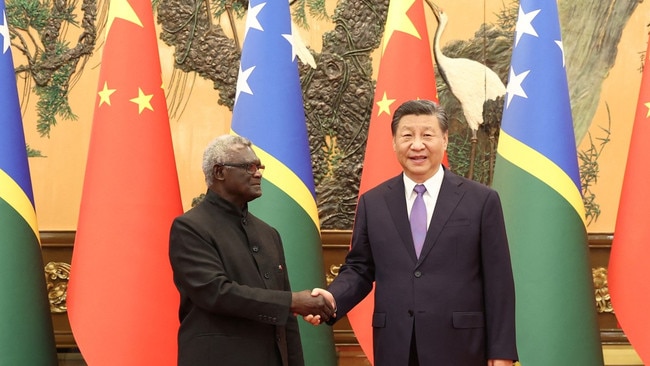

Then last year China announced a security deal with the Solomon Islands, which includes Chinese training of the Solomons’ police, the closest the country has to an army.

The incursion of Beijing into the security arrangements of a region previously dominated by the US and its ally Australia has galvanised governments across the world. This year alone the region’s biggest country, PNG, has been visited by the foreign ministers of the US and Britain and the leaders of Australia, Indonesia, India and France. Biden would have visited himself, if he had not been forced to return to Washington to deal with a budget crisis.

Manasseh Sogavare, the prime minister of the Solomon Islands, is pointedly snubbing Biden’s invitation. In a speech at the UN general assembly last week he saluted Chinese assistance as “less restrictive, more responsive and aligned to our national needs”.

Biden is doing his best to show that it is not all about US security concerns: the Pacific island leaders will spend time with John Kerry, the US climate chief, and Samantha Power, head of the US Agency for International Development, which will be dispatching Peace Corps volunteers to the region.

There is little doubt, though, about what the dominant theme of the meeting will be. In the long term the US will be hoping for more defence agreements like the one signed in May with PNG, which gives the American military “unimpeded access” to key bases for training, refuelling and deployment of ships and aircraft, including spy planes.

With Palau and Micronesia, Washington has recently renewed an arrangement called a Compact of Free Association, which entrusts responsibility for their defence to Washington and gives the US access to their strategic waters.

The Marshall Islands, however, has delayed agreeing its own new Cofa and is demanding compensation for the 67 US nuclear tests carried out in the 1940s and 1950s.

In an indication of the new reality, having suddenly become strategically interesting, the Pacific nations have discovered that they have a new and unaccustomed leverage and negotiating power.

“The strategic interest and attention we enjoy today will not last forever,” Henry Puna, secretary-general of the Pacific Islands Forum, said. “We must capitalise on it in a manner that will ensure sustainable gains for our region and for our people for decades to come.”

The Times