Jaws at 50: ‘we thought viewers would laugh, but they screamed’

Steven Spielberg’s classic terrified audiences and created a blockbuster 50 years ago, but problems with the mechanical shark and on-set rows almost led to it being canned.

Right up until the first audience saw the film, production designer Joe Alves worried that they would not be scared.

Throughout a troubled shoot the key mechanical props struggled with saltwater corrosion or made strange noises that reduced the crew to fits of giggles.

“I thought people were going to laugh,” Alves, 89, recalls of that 1975 test screening. “But they screamed.”

Jaws, which celebrates its 50th anniversary in June, was about to alter the course of Hollywood history.

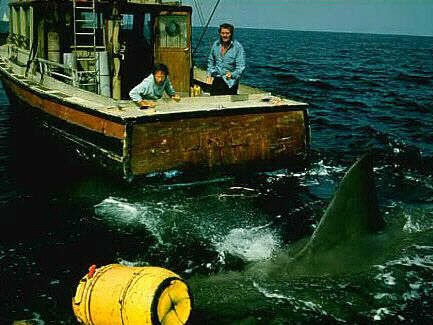

The film featured a great white shark preying upon a New England beach town and the unlikely team made up of a police chief, marine biologist and half-crazed fisherman sent to capture it.

It made a star of Steven Spielberg, its 28-year-old director, terrified a generation of moviegoers and invented the American summer blockbuster.

Before all that happened Alves found himself on a ferry in Massachusetts. He was attached to Jaws before Spielberg.

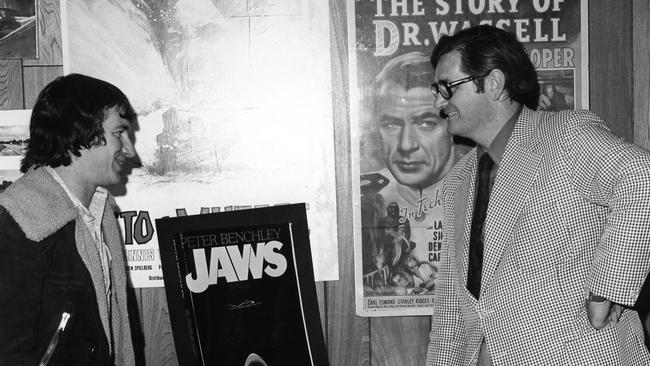

Producer David Brown handed him the galleys of Peter Benchley’s thriller (which went on to be a bestseller) and asked him to draw illustrations of scenes from the book to help pitch a screen adaptation to a studio.

Spielberg, who had been planning a pirate film, eventually chose Jaws. He and Alves agreed that they had to shoot on the open ocean with a 7.5m mechanical shark.

“It’s never been done before,” Alves recalls. “The Old Man and the Sea (released in 1958) with Spencer Tracy, they had this big marlin and it just lays there in the lake in the back lot, it just looked terrible.”

During a meeting at Universal, Alves recalls, a special effects expert insisted a shark of that scale could not be built.

The expert was working on a more important project: The Hindenburg, a disaster movie based on the 1937 airship crash.

“Jaws could be a bigger movie than The Hindenburg,” Marshall Green, a producer at Universal, told the meeting. The room burst into laughter.

“It was treated like a dumb shark movie and they had a young kid who was gonna direct it,” Alves recalls.

Around November 1973, Alves was told by the studio that the model sharks he had designed had to be ready in two months. A team under the guidance of the legendary special effects artist Robert Mattey got to work.

Alves also was hunting for a location to stand in for the fictional Amity Island. At Benchley’s suggestion he caught a ferry to Nantucket to check it out, but bad weather forced the captain to turn back to Martha’s Vineyard.

“It was perfect,” Alves says. “All these little white picket fences, just a beautiful community.”

Jeffrey Kramer was a young actor when he read in a local newspaper that producers were hiring for a new movie. His agent secured him a meeting with Spielberg.

Kramer left the room certain he had got the job. “I’ve never done that before, nor since,” the 79-year-old, later a successful producer, says. He played Deputy Hendricks, a colleague of Roy Scheider’s Chief Brody.

Kramer loved working with Spielberg but the troubled production frayed the cast and crew’s nerves.

“The rumours were going around as we were doing it, because we were way over budget, that they were going to pull the plug,” Kramer says.

The production went over by more than 100 days and the initial budget of $4m doubled.

Spielberg was pushed to his limits. “The experience of making Jaws was horrendous for me,” he told the writer of a retrospective of his career.

Martha’s Vineyard may have been perfect when Alves visited in winter but during the summer when Jaws was filmed the ocean was filled with pleasure boats.

Spielberg would wait for hours for the horizon to clear, only to find the current had dragged the film boats wildly out of place.

Some days ended with no usable material. Then there were the three mechanical sharks, all called Bruce, after Spielberg’s lawyer.

“Salt water and mechanics do not get along,” Alves notes. The sharks suffered buoyancy issues and mechanical problems.

Universal chief executive Sid Sheinberg offered Spielberg the chance to cut his losses and scrap Jaws midway through production.

Instead the problems contributed to the greatness of the movie. Spielberg was forced to improvise and show less of the shark, a tactic that ultimately boosted Jaws’ sense of foreboding.

Alves recalls the test screening as the moment he knew Jaws was a success, when John Williams’ score ensured that no one would be laughing like the crew had.

Jaws grossed $476.5m, a record surpassed two years later by Star Wars, and changed the way films were marketed.

Alves still regularly speaks about Jaws and features with Spielberg in the forthcoming documentary Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story.

“We had no idea, we were just trying to make a really good movie,” he says.

“I worked hard on some movies and they just opened and closed.

So you never know.”

THE SUNDAY TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout