It’s essential we resist COVID-fatalism and maintain hope

“Every idiot who goes about with ‘Merry Christmas’ on his lips should be boiled with his own pudding, and buried with a stake of holly through his heart.” So said Ebenezer Scrooge, updated for 2020 by Scotland’s national clinical director, Jason Leitch, who has warned that the prospect of big family gatherings around the turkey this year is “a fiction”. Instead, he suggests that “people should get their digital Christmas ready”, raising the dismal prospect of a million glitchy Zoom calls conducted in paper hats.

In response, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Paisley, the Right Rev John Keenan, warns that Leitch runs “the risk of destroying all hope. Hope is perhaps the most precious commodity we possess. Without it we will fail to combat this pandemic, we will fail to care for ourselves … We must be very careful that we do not distinguish hope, the consequences of that would be devastating.”

The bishop’s words feel timely. Seven months into this pandemic, fatigue is growing and hope fading. In March we were told the country could “turn the tide” within 12 weeks. In July there was to be “a significant return to normality” by Christmas. The latest official line is that we should be in a better place by this time next year. But increasingly there are quiet mutterings that we may never be in a better place. Ministers are said to be less optimistic about the prospect of a vaccine than they once were. Various well-informed people have explained why neither shielding nor herd immunity are sensible options. Test and trace does not, at the moment, seem a way out of serial lockdowns.

In such a situation, it is easy to lose hope that things will change. I observe a growing group of people – the Grim Realists – who have decided that this is it. “There’s no way out. We’d better get used to it. We’re never going back to normal. Holidays are over. Hospitality is dead. So’s the high street.” The Grim Realists will give you ten reasons why a vaccine is doomed to fail before breakfast and will state with confidence that all exit doors are closed; it’s about living with the virus now, however miserable and muted life may be. Like the Scottish clinical director, they prefer the cold gruel of low expectations to false hopes.

I have come across rather a lot of this Covid-fatalism recently and wonder whether an absence of hope is a defence mechanism. With rock-bottom expectations, it is impossible to be disappointed. The Grim Realists seem to enjoy a greater level of certainty, too; if you forecast that 2021, 2022 and 2023 will look rather like 2020 then, as depressing as that prospect may be, at least you know where you’re heading. You’re on solid ground, not the shifting sands of hopes raised and dashed.

But it is important that we resist the siren cynicism of the Grim Realists and maintain hope as far as we can. Sure, telling people to be hopeful in a time of relentless bad news, bankruptcy, suffering and death can seem like whispering platitudes into a hurricane. Yet there is an urgent, practical reason why we need people to remain hopeful: continuing adherence to the rules. Most are deferring gratification from socialising in the expectation that gratification will one day come. If increasing numbers of people feel that nothing is going to change, they may wonder why they should bother sticking to the rules. This is why Leitch’s hope-crushing intervention in Scotland is unhelpful; if Christmas is written off in October, the people of Scotland may well feel the next two months of restrictions won’t change anything anyway, and rebel accordingly.

Most importantly, maintaining a sense that “this, too, shall pass” is essential to our national health – mental and physical. In his book Anatomy of Hope, the Harvard medical professor Jerome Groopman explains how hopeful attitudes can alter neurochemistry, blocking pain by releasing endorphins and setting off a chain reaction in the body: “hope can have important effects on fundamental physiological processes like respiration, circulation and motor function”. Hence the placebo effect, in which a hopeful outlook can turn sugar pills into cures.

For those struggling with mental health, feeling flickers of hope about the future is essential. Last week we learnt that depression and anxiety are spiralling among children. Little wonder: stuck indoors, missing grandparents, pulled in and out of school, absorbing the financial worries and rows of their parents. The young need to believe that this isn’t life from now on, that the world they are inheriting isn’t one drained of colour. Retaining hope is equally vital for the very old. When the next few years (at least) are glibly written off, what does that do to the spirits of an 85-year-old who wishes to enjoy seeing their family and going on holiday for a few years yet?

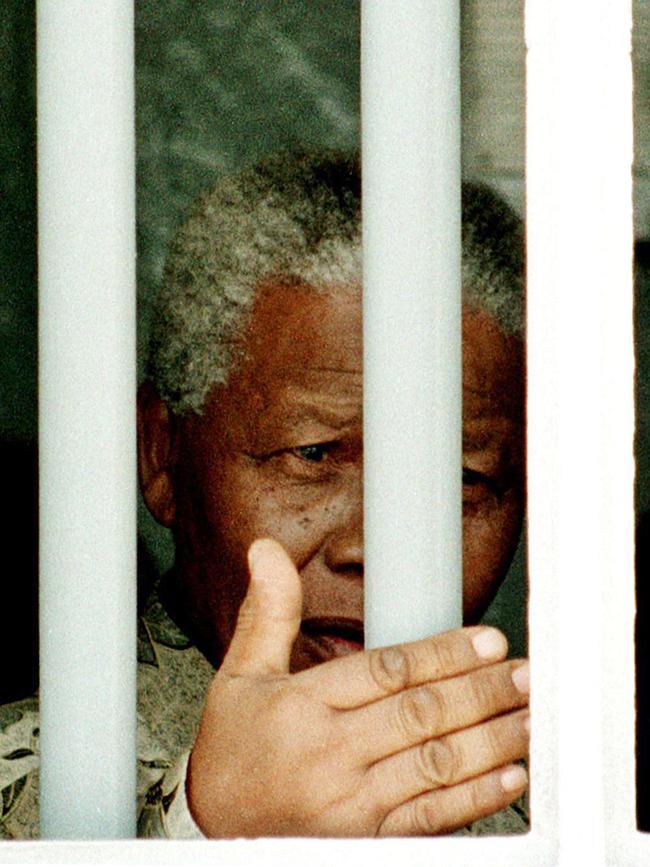

We know from those who have suffered much worse that hope is a muscular, practical tool for surviving hard times. From his cell on Robben island, Nelson Mandela wrote: “It is not so much the disability one suffers from that matters but one’s attitude to it. The man who says: I will conquer this illness and live a happy life is already halfway through to victory … hope is a powerful weapon even when all else is lost.” The psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, whose bestseller Man’s Search for Meaning reflects on the lessons learnt in Auschwitz, observed that those who survived were not necessarily the most physically fit, but those who did not lose hope. Nurturing the belief that a good life lay beyond was a life or death choice.

This is the important thing about hope: it can be a choice, not just an involuntary response dictated by our tendency towards optimism or pessimism. As Tennyson put it in the grief-stricken poem on the death of his friend Arthur Henry Hallam, In Memoriam: “I stretch lame handsof faith, and grope/ And gather dust and chaff … And faintly trust the larger hope.”

We can consciously reach for hope, too, by focusing on the pinpoints of light at the end of this tunnel. While vaccine hopes seem uncertain, great strides are being made on the treatment front. Stays in intensive care are shorter and the mortality rate is down. Trials of antibody therapies in the US suggest they may stop mild Covid from becoming severe. For the worst cases, progress is being made in immune therapy. Last week Paul Morgan, director of the Systems Immunity Research Institute at Cardiff University, said “we have seen very promising results where people who had reached the stage where there was no further therapy for them, where they were on ventilators, primed and ready at death’s door, have made startling recoveries”.

For all our sakes let us dwell on these victories, rejoice in the successes and – where possible – reach for the larger hope.

The Times