It’s all about balance: the neurones keeping you on your feet are in decline

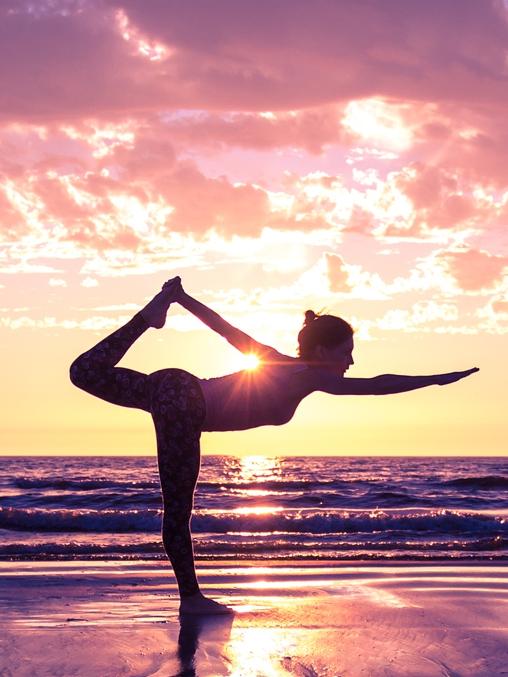

Negotiating the perils of ageing could be as easy as standing on one leg. These exercises could keep you a step ahead.

Your muscles and mind are tended to at the gym, and your cardiovascular fitness ramped up with running and Spinning. Yet when was the last time you worked at bettering your balance?

Of all the perils of ageing, falling is among the most prevalent. Figures from Britain’s National Health Service show that a third of people over 60 have falls, and about half of those over 80 do so at least once a year. Falls in the home are estimated to cost the NHS close to $AU830 million a year. Yet many could be avoided and, according to a recent review by the Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group, exercise plays a significant part in prevention.

What type of exercise you do makes a big difference. Researchers from the University of Sydney, Manchester University and the University of Oxford looked at 108 randomised controlled trials from 25 countries and found that some activities are better than others in protecting your body against this downside of ageing.

Professor Anne Tiedemann, a researcher in musculoskeletal health at the University of Sydney and one of the contributors to the Cochrane report, says that “dance, walking or resistance training performed on their own are not effective in preventing falls”. Activities incorporating standing and functional balancing moves, such as tai chi and some yoga postures, are far more beneficial.

Don’t think that just because you are superfit for your age you will be immune to deteriorating balance.

It affects us all. In research funded by the European Union and the UK Medical Research Council (MRC), researchers at Manchester Metropolitan University looked at balance in leading older athletes, all representatives of the British Masters Athletics Federation, to find out whether their supreme fitness levels help to offset the decline seen in less athletic people of a similar age.

Jamie McPhee, a professor of musculoskeletal physiology and the study leader, says that these athletes, whose ages ranged from 40 to 90-plus, displayed superior cardiovascular health, muscle strength, bone mineral density and metabolic health. “Some of these athletes are training 12 to 14 hours a week,” McPhee says. “In their sixties and seventies they are displaying many parameters of physical function that are the same as someone 30 years younger.”

However, none of this translated to better balance. Despite their physical prowess, the masters athletes were not much better at balancing than couch potatoes of the same age. “It seems that a reduction in muscle mass and strength that occurs with age is not the only reason why people fall as they get older. Diminishing balance is partly down to poor control of the muscles we have as our brain’s control of movement deteriorates.”

In our younger years we each have about 70,000 specialised nerve cells — motor neurones — in the lower part of the spinal cord that connect with our leg muscles to control balance and movement. McPhee and his team have shown that, by the age of 75, 40 per cent of these motor neurones have been lost, resulting in lower levels of co-ordination and balance in people with all levels of physical fitness. “It’s as much a part of ageing as greying hair,” McPhee says. “And there’s no evidence at all that staying fit with regular forms of exercise prevents it.”

He says that the only way to hold on to balance is to do specific training. And, according to Tiedemann, the best time to start is now. “If we consider that there is an age-related decline in muscle strength from about age 40 and that this is one factor that is important for balance, then ideally people should be thinking about exercise to maintain their ability to balance as early as possible,” she says. “We do know that risk of falling increases by around age 65, but it’s better to not wait until you fall to pay attention to prevention strategies.”

So what should we be doing to prevent a fall?

TAI CHI

The martial art tai chi uses a series of flowing motions that involve moving from one pose to another by gently shifting your bodyweight to challenge your balance. Don’t be put off by the low intensity — it really is something we should all consider trying and the Cochrane reviewers found it to be among the most effective ways of preventing falls; their evidence suggested a reduction of 19 per cent in the rate of falls.

There’s evidence that tai chi can help to lower blood pressure, heart rate and levels of the stress hormone cortisol, all of which can affect balance. Two years ago the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society reported that in a study of people who regularly did tai chi for up to a year, their risk of falling fell by 43 per cent.

One study showed that those attending tai chi classes performed better in balance tests than those who had spent the same number of weeks learning ballroom dancing. “Joining a tai chi class is an excellent prevention strategy,” McPhee says. “Most of the moves involve balance and are performed standing up.”

YOGA

In the Cochrane review, results suggested that standing yoga poses may be helpful in preventing falls. “Since a lot of yoga postures involve balance, it can be useful,” McPhee says. “However, the lying and sitting moves are not beneficial for balance.”

Iyengar yoga, which involves props such as bolsters and blocks to allow participants gradually to master the poses, seems to have particular benefits. A nine-week study at Temple University’s school of podiatric medicine in Philadelphia found that Iyengar yoga helped to improve the postural stability and balance of 24 elderly women. They showed significant improvements in balance factors such as an improved single-leg stance and “a pronounced difference in how pressure was distributed on the bottom of the foot, which helps to maintain balance”, the researchers reported.

It’s not useful only for older people. Exercise scientists from Northeastern Illinois University looked at the effects of yoga on a group of young male athletes who did classes twice a week for ten weeks. By the end of the trial, the men displayed better balance in tests such as holding the stork stand, a posture that involves standing on one leg, than a control group of male athletes who hadn’t introduced yoga.

STAND ON ONE LEG

This simple exercise is something we should be doing daily while brushing our teeth from our forties onwards, experts suggest. Once you can master it for 20 seconds, try doing it with your eyes closed. In his research McPhee has found that young adults can easily stand on one leg, eyes closed, for 30 seconds, whereas the average 70-year-old manages only four to five seconds.

“Even with the trained masters athletes, we found that those in their seventies could hold the position only for around seven seconds, which is not significantly better than average,” he says. “That shows us that the ability to balance this way is affected by factors other than strength and fitness, and needs to be practised regularly to prevent a decline.”

According to findings from the UK’s MRC, a study of people in their fifties showed that those who could stand on one leg for ten seconds with their eyes closed were the most likely to be fit and well in 13 years’ time. If they managed only two seconds, they were three times as likely to die before the age of 66. “Once you can do the eyes-closed, single-leg stand, you need to challenge yourself more,” McPhee says. “Try moving your centre of mass by swaying on one leg with eyes closed and then try tying your shoelaces on one leg.”

VIBRATION PLATFORMS

You have probably seen vibrational platforms at your gym, but have you used one? Platforms such as the Power Plate are designed to move in different directions with micro-vibrations that are said to challenge balance. Evidence is sketchy — the Cochrane review failed to unearth anything convincing in their favour when it comes to fall prevention — but McPhee says that they may be useful and will offer a bit of variety to your balance training.

In 2017 a study in the European Review of ageing and Physical Activity found that an eight-week program of “whole body vibration” training using these platforms improved the stability and balance of a group aged between 65 and 80.

Hop on and try a single-leg balance with foot reach — standing on one leg as you extend the other leg forwards and backwards while standing on the vibrating platform.

LOSE WEIGHT

If you are overweight, your risk of falling as you get older is heightened. “Obesity negatively affects postural control and balance and is a major risk for falling,” McPhee says. “In our trials we have found that very overweight people just can’t stand on one leg with their eyes closed — their centre of mass rocks beyond a point that they can control.”

Being overweight is also a risk factor for type 2 diabetes, which McPhee says presents its own problems relating to balance. “People with type 2 diabetes are prone to developing peripheral neuropathy, or nerve damage, in the bottom of their feet, which affects the feedback messages the brain receives about balance.”

This loss of neural feedback is irreversible. “Balance can be restored a little through specific exercises done regularly,” he says. “But people with accelerated ageing through conditions like obesity and type 2 diabetes do fall over all the time.”

HAVE A HEALTH CHECK

Our ability to stay upright is down to the brain knowing the precise position of the body, even when our eyes are closed. “The brain knows what’s stable and what’s not,” McPhee says. “But as we age we rely more on visual cues, and that can cause problems.”

Disorders of the vestibular system, including eyes, inner ear and brain, can severely impair balance, so regular sight and hearing tests are crucial. Other health conditions that can impair balance include Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, dementia, stroke, diabetes, arthritis, cataracts and other eye diseases, and depression.

“Human balance is mainly affected by the efficiency of internal factors that include vision, proprioception, muscle strength, joint range of motion, reaction time and the vestibular system,” Tiedemann says. “All of these body systems decline with age, leading to a reduction in balance ability with age.” An annual wellbeing assessment check is a must.

The Times