A man who has spent a career on the fringes of political life, as an environmental lawyer famous mostly for peddling pseudoscience about the dangers of vaccines, is suddenly centre stage, riding a wave of favourable media coverage and registering polling numbers that, while not suggesting he should be readying rolls of wallpaper for the White House, certainly indicate he is much more than a wild-eyed long shot.

Since he announced his bid for president last month, challenging President Biden for the Democratic nomination, Kennedy has surprised party leaders with his rising appeal. A poll last week for CNN put him at 20 per cent among Democratic primary voters, with Biden well ahead at 60 per cent. But that level of support for a complete outsider against a party leader with all the benefits of incumbency is startling – and alarming to leading Democrats.

Another poll for Echelon Insights indicated that Americans have a more positive opinion of Kennedy than of Biden: 44 per cent said they view him favourably, ahead of the 40 per cent saying the same about Biden; 22 per cent view him unfavourably, against 58 per cent for the president.

Every president who has faced a challenge of any significance from within his own party in the past 60 years has either been forced to stand down or gone on to lose the ensuing general election: Lyndon Johnson in 1968, Carter, at the expense of Teddy Kennedy in 1980, George HW Bush with Patrick Buchanan in 1992.

It’s possible that voters’ confidence in the ageing Biden is now so low that a sock puppet looking vaguely youthful and at least conscious could mount a serious challenge to the president. But it’s also possible that Kennedy is tapping into something seismic in America’s shifting political geology.

His relative success is another indication of the continuing, and bipartisan, appeal of populist politics: in his stump speeches and media appearances he hammers a relentless message, slamming overweening government, powerful corporations, a foreign policy he says is characterised by endless warfare and an environment of encroaching authoritarianism and censorship.

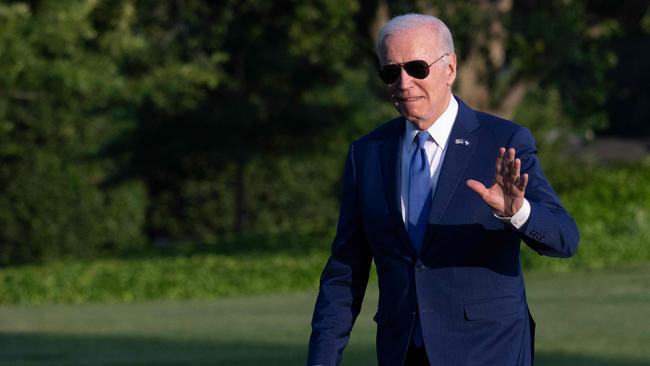

When I sat down with him this week in New York, between campaign stops in San Diego on the west coast and Philadelphia in the east, RFK Junior was in combative mood. Fit and trim at 69, equipped with the distinctive Kennedy good looks and a raspy voice that recalls a million famous family speeches, he seems happy to play the Democratic rebel with a cause. Most of the Kennedy clan, who are close to Biden, have disowned his campaign and have distanced themselves from some of his more outlandish positions.

He has become best known in the past 20 years for his denunciation of vaccines, and for associating himself with what can only be described as dangerous quackery, especially over the MMR vaccine and the claim that it causes autism in children. He is unrepentant when we speak, saying vaccines “are producing a tsunami of chronic diseases in our country”. But he knows the issue resonating with voters is his staunch critique of the stringent Covid mandates during the pandemic, and it is difficult to disagree with him as he describes the immeasurable damage they have done to the economy, mental health, education, and the fragile cohesion of the United States.

“It’s not a partisan issue,” he tells me. “President Trump implemented [lockdowns]. It cost sixteen trillion dollars to our country. It shifted a trillion dollars in wealth from the middle class to the super-rich. It was an attack on the poorest people in our country. We created a billionaire a day during the pandemic … And American children lost 22 IQ points, a third of children require remedial education up through high school and some of them will never recover from what we did to them.”

He also has a point when he condemns widening censorship by government and corporations in the name of crushing “misinformation.”

Implicitly invoking the themes of his father’s campaign in 1968, he is scathing about the power of big companies and wealthy Americans, and, like Bobby Kennedy Sr, is tapping into rising anti-war sentiment by opposing US aid to Ukraine, although it’s a considerable stretch to say, as he does, that Kyiv is “in the middle of a proxy war between two great powers, neither of whom is fighting in the interest of Ukraine”.

He insists his bid to dethrone Biden is nothing personal and that he wants to avoid an acrimonious battle. “I ran my uncle’s [Teddy’s] campaign in the southern states in 1980. And that was a very, very bitter campaign,” he says. “And that bitterness I think percolated down to, you know, the people who supported him within the Democratic party … I’ve known President Biden. I’ve had a long friendship with them. I’m not going to make this a personal campaign, but I am going to talk about issues and that is good for our democracy.”

Still, it seems plausible that while this latest bid by the member of America’s most famous family won’t end with another Kennedy in the White House, its main achievement will be, as it was in 1980, to oust a fellow Democrat from it.

In a country in which the politically unimaginable has become routine, perhaps it isn’t a surprise that the latest name to emerge in the front ranks of presidential contenders is that of a Kennedy. Sixty-three years after his uncle was elected president, 55 years after his father’s campaign for the top job ended in an assassin’s bullet, and 43 years since another uncle’s bid did irreversible damage to Jimmy Carter’s hopes for re-election, Robert F Kennedy Jr is, implausibly, reviving the political fortunes of the most famous name in Democratic politics.