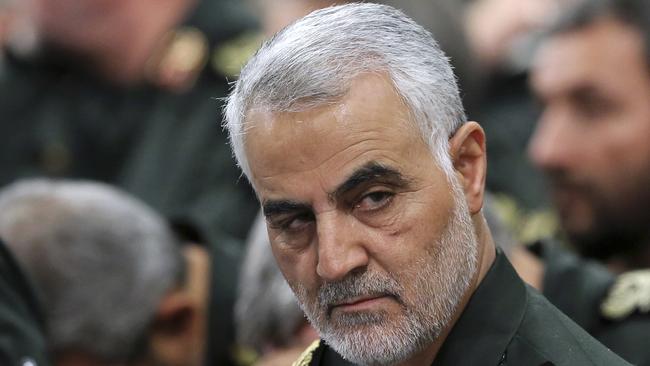

Iran general Qassem Soleimani obliterated by push of button 11,000km away

Qassem Soleimani showed brazen confidence in his last moves before his death by remote.

Maybe, after 20 years as Iran’s master fixer across the Middle East’s troublespots, he thought he was invincible. Maybe he had put trust in US President Donald Trump’s insistence that he had no desire for war with Iran and wanted to withdraw from the region altogether.

The general certainly knew that US and Israeli leaders had for years plotted his assassination and then baulked at the possible consequences.

Whatever the reason, the last moves in the great game played by Major General Qassem Soleimani, 62, head of Iran’s Quds Force, showed a brazen confidence.

When he flew from Damascus to Baghdad late on Thursday night, from one of the key capitals Tehran believes it has in its pocket to another, he did not use some secret military or militia air base. He flew in his personal, Iranian-regime jet to Baghdad’s main international airport.

As he knew, the airport is not only a daily route for local, foreign and Western civilians and soldiers in and out of the country, it is adjacent to a military base shared between the Iraqi counterterror service and US forces.

There was little attempt to keep Iran’s eggs in separate baskets. He was travelling with senior aides from the Iranian Revolutionary Guard: Brigadier-General Hossein Jafari Nia, Colonel Shahroud Mozafari Nia, Major Hadi Taromi and a captain, Vahid Zamanian.

He was met by Iran’s most senior operative within the Iraqi security and paramilitary forces: Jamal Jaafar Ibrahimi, better known as Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the man who after the US-UK invasion of Iraq in 2003 set up the country’s answer to Lebanon’s Shia militia Hezbollah.

Iraq’s Kataeb Hezbollah is accused by the Pentagon of being behind recent rocket attacks on US-occupied bases in Iraq, and five of its own compounds were hit in retaliation by F15 jets on Sunday.

Muhandis defected to Iran from the regime of Saddam Hussein in 1979 and was recruited as an agent in the ensuing war between the countries by the Revolutionary Guard. He has served it since.

Alongside Muhandis to greet Soleimani was Mohammed Ridha, a senior figure in the Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU), the official Iraqi government-recognised umbrella group for Iraq’s militias. Muhandis’s formal position was deputy head of the PMU, answerable directly to the Iraqi prime minister, Adel Abdul-Mahdi.

All seven men piled into a Toyota SUV and a Hyundai minivan and set off out of the airport by the main road. But America’s formidable surveillance capabilities, masterminded from the National Security Agency in Maryland and helped by a giant CIA operation in Baghdad, had Soleimani on their radar.

Two MQ9 Reaper drones were in place, sent from al-Udeid military and air base in Qatar. The back-up drone was not needed. Just two missiles were used by operators at the US Air Force base at Creech in Nevada, one for each of the two vehicles. The strike had been approved, it is understood, at the same time that President Trump authorised Sunday’s attack on Kataeb Hezbollah.

Airport security was at the scene immediately, with phone cameras. The images that quickly circulated on social media were graphic. In one, the general’s vehicle was still blazing. In another, a bloodied arm stretched out, its curled hand bearing a recognisable ring.

The reaction was immediate. Crowds gathered in Soleimani’s home town of Kerman and in Mashhad, one of the regime’s bedrocks of support.

Iraq was also in uproar. The government clearly found it hard to believe that a notional ally could assassinate Muhandis, officially a senior government official, on Iraqi soil.

“The assassination of an Iraqi military commander holding an official position is an aggression against Iraq, the state, the government and the people,” the Prime Minister said. “Carrying out liquidation operations against Iraqi leadership figures or from a brotherly country on Iraqi soil is a flagrant violation of Iraqi sovereignty, a blatant attack on the dignity of the country and a dangerous escalation that ignites a devastating war in Iraq, the region and the world.”

Other Iraqis felt differently, as did opponents of Iran’s influence across the Middle East. Footage captured protesters in Baghdad and southern Iraq dancing in the street – Soleimani was said to have ordered the crackdown on recent demonstrations that led to hundreds being shot dead.

In Syria, rebel groups that have been gradually crushed in their fight against President Bashar al-Assad by Soleimani and Iran’s Russian allies handed out sweets to children. In Lebanon and elsewhere, relatives of people killed in Iran’s assassination programs punched the air in delight.

The US was among the first countries to order its citizens to leave Iraq. France, the Netherlands and others followed. No one knows where Iran’s revenge for the loss of its favourite son will come, but it is hard to believe that it is not coming soon.

Soleimani was not merely Iran’s most senior military commander. He was a towering figure second only to the supreme leader, the only person in the country to whom he was answerable and whom it was often whispered he would replace should the regime fall.

In Iran and among its Shia allies across the Middle East, Soleimani enjoyed near mythical status, described in Time magazine’s 100 most influential people as “James Bond, Erwin Rommel and Lady Gaga rolled into one”.

His rise to power came via the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) set up after the 1979 revolution to protect the Islamic Republic and enforce its ideological aims. The IRGC cemented its hold after the Iran-Iraq War, ending up with vast control over the country’s economy and resources.

In the 1990s Soleimani was given command of the Quds Force, an elite unit that undertakes missions outside Iran’s borders and which had already established Hezbollah as a client militia in Lebanon. The force’s role is like few others anywhere in the world; equivalent in American terms to a combination of the CIA and special forces.

It was in that role that Soleimani became the chief architect of Iran’s regional strategy, creating the arc of influence that Iran terms its “Axis of Resistance” – and others the “Shia crescent"- extending all the way through Iraq, Syria and Lebanon.

Soleimani remained a shadowy figure in that role for years. It was only in October that he revealed in a television interview that he had been in Lebanon in 2006 helping to direct the conflict between Hezbollah and Israel.

He had seized the opportunity provided by the 2003 US invasion of Iraq to gain a foothold from which to begin sketching Iran’s influence towards the Mediterranean. Through a network of Shia militia he launched attacks on American soldiers in Iraq, seeking to tie them down and then scare them off.

It was the uprising in Syria that would bring Soleimani out of the shadows, emerging as the public face of Iran’s intervention there. He appeared in photographs visiting troops on the battlefield, in documentaries on Iranian state television and even in a popular music video.

By the time of his death, the short, silver-haired general was a full-blown celebrity, with millions of followers on Instagram, the only social media site not formally banned in Iran. Much of his power was derived from his close relationship with Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who previously referred to him as “a living martyr of the revolution”.

The 9/11 attacks brought Soleimani and the US together in common cause against the Taliban. Soleimani gave the Americans guidance on where to strike the group and intelligence on al-Qa’ida operatives. The relationship imploded, however, after George W. Bush named Iran as part of an “axis of evil” in his state of the union address. “Soleimani is in a tearing rage,” Ryan Crocker, the deputy ambassador in Kabul at the time, remembers an envoy telling him.

The battle against Isis, beginning in 2015, brought the US and Soleimani back in common cause as the general commanded Shia militia against the jihadists. American commanders were forced to hold their noses and join in the fight, launching airstrikes in support of Iranian-backed Shia militia.

The recent mass protests against the Iraqi government and Iran’s influence over it saw Soleimani draw further on his political skills, flying in and out of Baghdad to direct the government’s handling of the crisis. It was in Baghdad that he met his end in a US drone strike.

Soleimani had been in the West’s sights many times before. Presidents Bush and Obama passed up opportunities to assassinate him, as did Israel, determining that the fallout from such an action could be too great. The pressure on Tehran to retaliate to the loss of such a towering figure will be immense.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout