International alliances key to containing China

What seems to be emerging from the Biden team, some of whom were involved in Barack Obama’s supposed pivot to Asia, is the idea of intersecting coalitions to tackle the different dimensions of the Chinese challenge. The biggest surprise is how central to this planned new order is the axis between the US and Japan. If it all comes to pass, America may be able to guarantee its future as a Pacific power, China will be forced to scale down its ambitions – and Japan will be seen as the indispensable player in the East.

Trump was right to link the perception of American decline with the unchecked expansion of China’s trade and influence. But it seemed to him to demand an epic bout of arm-wrestling, a trial of strength and willpower between two muscular states. In fact, containment is more successful if it’s conducted like the Lilliputians’ restraint of Gulliver by tens of thousands of tiny threads.

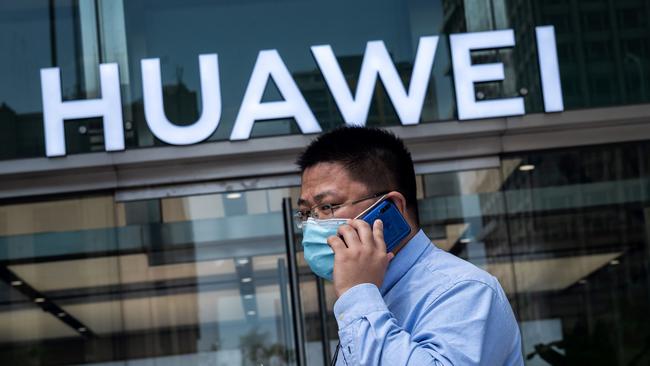

The need for containment is clear. Earlier this month a Beijing official preparing the next five-year plan said that the national priority had to be technological self-sufficiency. China is still too dependent on semiconductors from America or America’s friends, which has made it vulnerable to sanctions. Expect higher R&D spending in sectors such as biotech, semiconductors and clean energy vehicles. Naturally, this will also entail more industrial espionage. And Huawei is planning a huge chip plant in Shanghai to wean it away from US tech.

The new coalitions emerging out of common fears about China go beyond geographical proximity to Beijing. Their membership is also less formal than Nato’s, but all assume US leadership. The quad – India, Australia, Japan and the US – is the core of Chinese containment. A diplomatic and trade spat is poisoning Australia’s relations with Beijing; Indian soldiers have exchanged blows with Chinese border troops in the Himalayas; China covets some Japanese islands. The quad could be supplemented by a T12 of technologically advanced democracies that are queasy about Beijing vacuuming up their industrial secrets. This group would comprise the UK, France, Germany, Canada, South Korea, Australia, India, Sweden, Finland, Israel and, of course, the US and Japan. It would be the smartest forum for coming up with a common position on Huawei’s involvement in the rollout of 5G.

The existing forum of the G7 can influence the direction of the world economy and includes the UK, Japan and the US. And on questions of governance, such as the manipulation of countries that signed up for Beijing’s Belt and Road project and which now find themselves ensnared by debt, a notional D10 of democratic powers could keep an eye on Chinese subversion. This would include many members of the T12, with the US, Japan, UK, India and Australia playing outsized roles. Britain could seek to join the quad, even if its shores are a long way from the Pacific. It would join two other members of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing arrangement, the US and Australia, and has a keen sense of how China’s bully-boy tactics function across the world.

These clubs serve two purposes: to bring a global consensus around the threats posed by a fast-rising power and to establish that China is not simply an Asian problem. It’s not so much about creating new institutions but understanding that a multinational approach, rather than a die-in-a-ditch great power slugfest, is the most efficient way of staying safe and vigilant. There are a growing number of bilateral deals too, built on the promise of joint military action if someone is under threat. A new Australian-Japanese defence agreement provides for joint exercises, Japanese escort of Australian vessels, and alertness to a Chinese land-grab of the Senkaku islands, which are also claimed by Japan. Would that be enough to deter a Chinese fait accompli against Japanese territory? Perhaps not, but the sense of an Indo-Pacific community is already galvanising the region. India, which once identified itself as non-aligned, now considers itself free to choose its allies. And at a time when its border troops are being beaten up by the Chinese, that freedom translates into closer co-operation with the US. Japan has been holding marine landing exercises with units from all four of the US services. The Japanese defence ministry is trying to raise its budget by more than 8 per cent.

The former prime minister Shinzo Abe learnt how to navigate around Trump’s eccentricities but there was always a lingering doubt in Japan, as in much of Asia, about what would happen next. If Trump secured the deal of the century with China, would he hail President Xi as his new partner and leave his friends in southeast Asia hanging? These questions have not been resolved by the arrival of Joe Biden. In his rush to win Chinese support for a climate change agreement he might become an unreliable ally to those who want to stall the challenge from Beijing. It’s a multilayered threat that ranges from cyberintrusion to gunboat diplomacy, from buying foreign politicians to manipulating the media – and it needs to lose its swagger.

Joe Biden presented himself as the candidate of the old normal, the carpet-slippered president who would Make America Sleep at Night Again. But the country’s nervous exhaustion was only partly down to the deranged tweeting from the White House. China, rather than Trump, remains the great global disrupter and the new president will have to concoct a plan to contain Beijing’s sprawling power. Until Biden comes up with the goods, the world will be gripped by a dull throb of anxiety.