In the event of Armageddon, desperately seek kelp

We could survive the wintry aftermath of a nuclear conflict. But it would involve a lot of seaweed, the mass relocation of crops and extracting sugar from paper.

First the bad news: a nuclear conflict has occurred, killing hundreds of millions and throwing enough soot into the air to block out the sun for a decade.

Now the good news: there is a chance we can get through the resulting years of endless winter without the survivors starving. But it’s going to involve a lot of seaweed, the mass relocation of crops and extracting sugar from paper.

An international academic collaboration has produced a road map for surviving an “abrupt sunlight reduction scenario”. After an asteroid impact, a huge volcanic eruption or an exchange of nuclear weapons, most of the deaths could well come not from the catastrophe itself, but as a result of the mass starvation that follows crop failures.

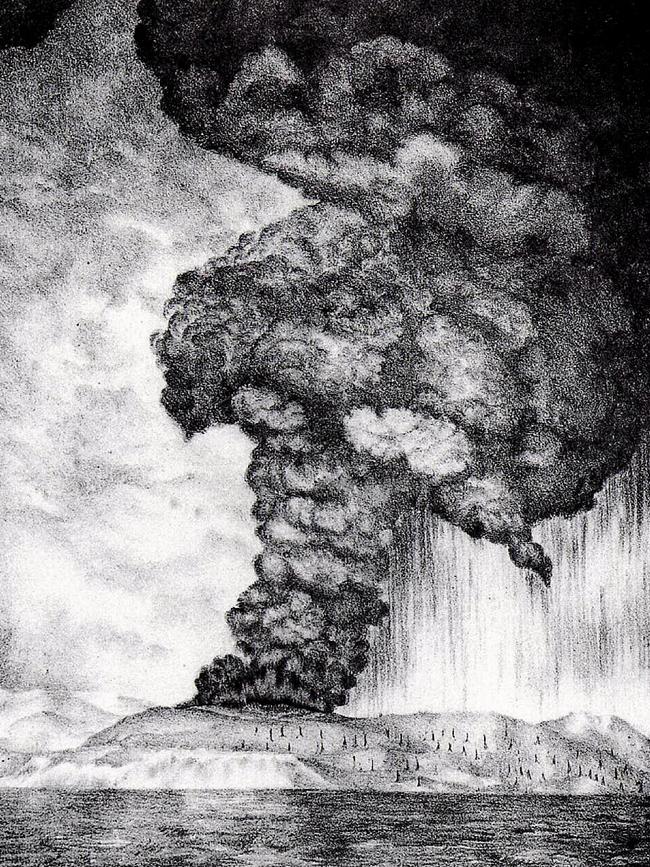

Even a relatively minor eruption, such as that of Krakatoa, put enough soot in the air to cause 1883 to be called the “year without a summer”. What if there were two, three or five years without a summer? Is starvation inevitable?

Not, a new paper contends, if we prepare well enough. With sufficient global co-operation it is possible, the authors argue, to keep the flame of civilisation burning.

“We’re trying to promote preparedness – a culture of having institutions, government and companies prepared for a kind of global catastrophe that has been quite neglected,” said Juan Garcia Martinez, from the Alliance to Feed the Earth in Disasters, which works with scientists around the world.

He and his colleagues have looked through the options available to humans in such a scenario and concluded, in the journal Nutrients, that there are three key phases.

In the first, immediately after the catastrophe, we would be reliant on stored and legacy foods. The world has a few months of supplies at any one time, which will be rapidly depleted. Fish are likely to last longer than animals on land – so should be exploited immediately. On top of that, there will be livestock, which are a highly inefficient way of making calories. Most could be slaughtered, with some ruminants kept on, as they can make milk from indigestible grass.

Using these resources wisely, reseachers argue, will buy time to scale up other food sources – not least through a scheme to turn humans into a kind of ruminant too. With the mass death of forests, there will be a lot of wood. Within that wood is a lot of energy, extracted today as a by-product of paper-making. Although we cannot access it, chemical processes can.

Taking sugars from wood could be part of the second phase, starting about six months later, allowing time for the logistical effort required to rebalance the Earth to make as many calories as possible from as little incoming energy as possible.

Key, said Garcia Martinez, would be for staple crops to be shifted closer to the equator. “That would allow us to use what little sunlight we might have left in the most efficient way possible.” Potatoes, which need less sunlight, will need to be sowed rapidly. And crucially, in part to cover nutrient deficiencies, seaweed farms will need to be built. Seaweed requires less sunlight and is better protected from radiation.

Although it could be technically feasible to feed the world following a loss of sunlight, whether it is politically possible – especially if there has been a nuclear conflict – is a different matter.

That is precisely why, says Garcia Martinez, we need to think about this now. “We believe that by being more prepared for this type of scenario, it would reduce the likelihood and severity of a potential collapse of civilisation.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout