‘I have always wanted to be a good human being, but … ’

Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour talks about his youthful arrogance, his guilt over Syd Barrett’s breakdown – and poisonous rows with Roger Waters.

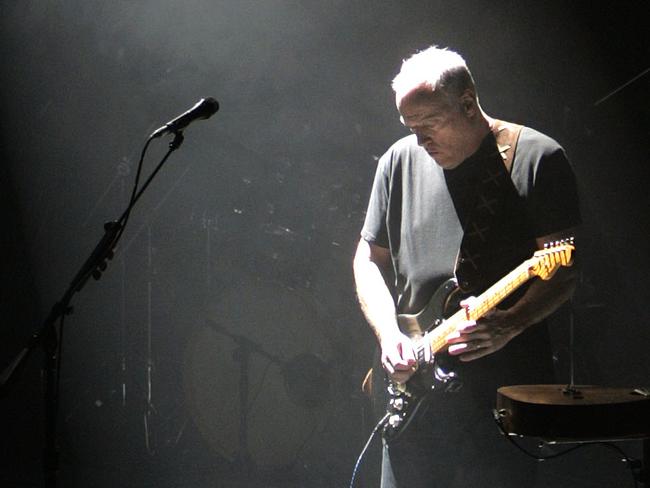

‘HEY, Will. Don’t give up the day job,” says David Gilmour after lending me one of his guitars, on which I have duly massacred the delicate ’60s folk classic Blues Run the Game. Which is rude of him, if good advice. The co-architect of Pink Floyd’s yearning epics of quiet desperation, the singular genius behind such indelible masterpieces as Wish You Were Here and Dark Side of the Moon, is on a boat moored by a bank of the Thames near Hampton Court, backing on to a garden designed by 18th-century landscape architect Capability Brown. Pink Floyd’s The Division Bell was recorded in secret here in 1993, and Gilmour has been using it as a base from which to work on Luck and Strange, a solo album on which, at 78, he’s reflecting on a lifetime in popular music and its cost. As his rather blunt assessment of my own abilities proves, you don’t become one of the greatest guitarists of your generation by having a quick strum after work.

“I’m thinking about death and mortality constantly,” Gilmour says when I ask if the encroaching years informed Luck and Strange’s reflective tone. Just to the right of us is the Fender Esquire on which he recorded Pink Floyd’s Run Like Hell; next to that is a Stratocaster formerly owned by Jimi Hendrix.

“I’ve always been that way. If you listen to Childhood’s End (from Pink Floyd’s Obscured by Clouds, 1972), you’ll find the same topic. In 2020, at the beginning of Covid, there was a strong belief that a large percentage of the population might die and it was terrifying. Those were the preoccupations that Polly inserted into the lyrics.”

That’s novelist Polly Samson, Gilmour’s wife and creative partner since 1994, who appears to be writing from her husband’s perspective, particularly on the title track, which takes stock of his generation never having had it so good.

“We were the baby boomers,” Gilmour confirms. “We had a magical moment with the hippy movement and the distinct idea that the world would be a better place. Right now we’re going into a darker world. Putin is doing an admirable job of keeping the ghastliness going and it is scary. Is that moment we had an unusual one? That’s what we were thinking about.”

Gilmour says he and Samson spend a lot of time talking about this kind of thing, after which she takes a piece of his music in its infant state and comes up with the words on her own. “I’ve written a few good lyrics over the years but not half as many as the tunes I’ve come up with. So I wanted Polly to do the lyrics because she’s so brilliant at getting into other people’s heads. Like that line, ‘How will we part? Will I hold your hand, or you be left holding mine?’ (from Dark and Velvet Nights). It was from a poem she wrote for me and it captures the feeling of who will go first precisely.”

Gilmour is from the generation of rockers who taught us how to stand up for ourselves, how to be rebellious, how to deal with the pains of love and the search for meaning. What they didn’t teach us is how to grow old and die.

“But as these people get older they’re inevitably going to think about it,” he says. “I’ve always thought about them. I remember having a realisation at 13: we’re all going to die. It became a bit of an obsession and it soaked into Pink Floyd.”

About two decades ago Gilmour replaced being in the Pink Floyd gang – if gang is the word for a socially incompatible group of men simmering with unspoken resentment for one another – with the family gang. Back in 2020, Gilmour and Samson were preparing to tour the country with a literary and musical show for A Theatre for Dreamers, her novel about bohemian life on the Greek island of Hydra in the ’60s. Then lockdown hit and everything was cancelled. Their son, Charlie, suggested doing online shows from their house in Sussex, and daughter Romany agreed to sing in the absence of anything else to do. That led to one of the most touching tracks on Luck and Strange. Between Two Points is a cover of a song about lack of self-worth by an obscure indie duo called the Montgolfier Brothers, and Romany’s oddly expressionless, strangely moving vocals suit it perfectly.

“There must be a little bit of magic to the family voice because Romany’s worked so well with mine,” Gilmour says. “I thought, ‘I’m a big old bloke and Between Two Points is vulnerable, so maybe we should try Romany’. She was down from Goldsmiths university for the weekend, and wanted to get back because she had an essay to write, but I asked her to do this song first. She was going, ‘Nooo, haven’t got time’, but she did it. Then I drove her to the station.” Now it’s the album’s standout moment.

Gilmour says he has no formula and doesn’t really know what he’s doing from one album to the next. Was it like that even in Pink Floyd, when there were three other people to contend with?

“Too long ago to remember,” he says, although I have a feeling he remembers more than he’s letting on. “I had some lovely times in my old pop group. But Roger (Waters) left the band when I was still in my 30s and Rick (Wright) is dead, so the relevance of all that stuff has vanished for me. I haven’t spoken to Roger for almost 40 years. I can’t make connections back to Pink Floyd any more.”

Pink Floyd went incredibly well, of course, until it went incredibly wrong. You have to wonder why Gilmour and Waters’s relationship deteriorated so badly that it got to Samson accusing Waters not only of being “anti-Semitic to your rotten core” in February last year, after the singer and bassist made inflammatory comments about Ukraine and Israel, but also of being a “tax-avoiding, lip-synching, misogynistic, sick-with-envy megalomaniac” for good measure. Gilmour backed up her tweet with a rather more circumspect: “Every word demonstrably true.”

“Listen. This is not a topic I’m going to discuss,” Gilmour says with the commanding air of a man fully aware he is going to be asked about it anyway. “Polly was boiling over with something and she put it out there. I put out a tweet agreeing with it, which I do, 100 per cent. But who knows the mysteries of that crank’s mind? It is a topic that I will one day talk about but now is not the time. It would obfuscate everything I am trying to do.”

One guesses Samson is not a character to be messed with either.

“She’s reasonably forceful, can be outspoken, very sharp and eloquent,” he says of his wife. “She’ll say to me, ‘Get in the studio and do some recording!’. She is very much at the heart of the team.”

Luckily Gilmour is happier talking about what will always be, for many, the most fascinating period of Pink Floyd’s career. The band’s original leader, Syd Barrett, led them through 1967’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, a debut of glorious psychedelic whimsy reminiscent of Lewis Carroll’s eerie, kaleidoscopic visions of the childhood imagination. It was released shortly before Barrett underwent a mental disintegration from which he never recovered. Gilmour, an old Cambridge friend, came in to take Barrett’s place, and he and Roger Waters also helped Barrett out on his two beautiful, fractured 1970 solo albums, The Madcap Laughs and Barrett. I wonder what those sessions were like.

“Syd wasn’t really in a state to do anything,” says Gilmour, who lived next door to Barrett at the time, in a flat on the Old Brompton Road in west London. “EMI were going to shut the whole album down because it was taking so long, so Roger and I said: ‘Give us another five days and we’ll finish it’. It wasn’t easy. Syd could be enormously fun or enormously difficult, and quite often you had absolutely no idea what he was talking about. It plainly wasn’t nonsense to him, it meant something, but it was like he was speaking a different language. And it was murder, trying to play drums to a track when all you had was Syd’s guitar going all over the place.”

This was about the time Pink Floyd were becoming enormously successful. They were at the height of their ambition and didn’t have the time or, arguably, the maturity to deal with Barrett’s breakdown. Gilmour later eulogised him in 1975’s Shine on You Crazy Diamond, and a heavy-set man with a shaved head and tormented eyes turned up during its recording session. It took them 45 minutes to realise it was Barrett.

“We didn’t recognise him for quite a while,” Gilmour says. “There was a lot of guilt involved but by then we were snowballing down our mountain and too much success brings its own kind of madness. Deeply unqualified people are thrust into positions of power and we’ve all seen where that can lead, destroying your life with drugs and so on.”

There is a song on the new album called The Piper’s Call, which appears to address that very subject.

“It is. Polly is writing about me and my own former wild times.”

How, then, has he managed to stay sane?

“I’ve always wanted to be a good human being but being in a successful rock’n’roll band involves single-mindedness, stubbornness and a certain ruthlessness – and you do end up thinking: Is this the way I want to be? Is it fair to other people? You end up being deferred to way too much. We were incredibly arrogant. Did exactly as we wanted. Wouldn’t even let the record label hear the album until it was finished. Our attitude to them was, ‘Did you make a profit? Yes? Then shut up and let us get on with it’.”

Gilmour was always cast as the laid-back one countering Waters’ burning rage and ambition. But he had drive from the start, he concedes. “I must have done. Can’t see it in myself but it is in there, lurking.”

“I’m playing Madison Square Garden on the night of the American election,” Gilmour continues, in a tone that suggests he is only now questioning the wisdom of this decision. “Should I be doing that with the state of the world as it is? Still, I’m thrilled with this album. It is the best solo album I have ever done.”

The Times.