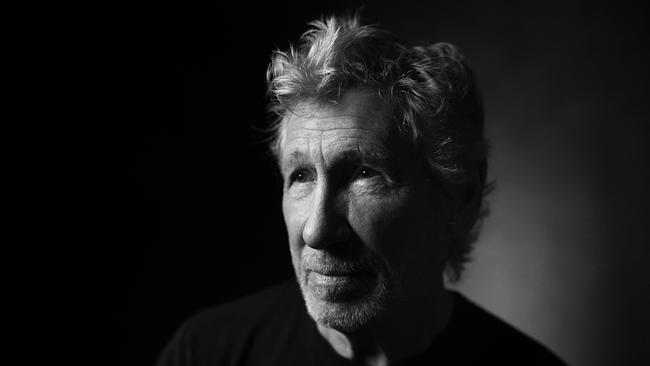

Album review: Roger Waters re-records Pink Floyd’s classic Dark Side

Though only 29 at the time of creating The Dark Side of the Moon with his bandmates, Waters remains fixated — and has re-recorded the album 50 years later. Why? | REVIEW

Album reviews for week of October 6 2023:

PROGRESSIVE ROCK

The Dark Side of the Moon Redux

Roger Waters

SGB Music / Cooking Vinyl

Psychological Evaluation, Patient R Waters, aged 80: Mr Waters makes claims to at least one cohering personality he calls “Pink Floyd”. A well-known musician, he defines his former group as an extension of his consciousness and appears unable to make healthy distinctions between the collective and a need to subordinate them into his autobiographical mythos. Previous assessments of Mr Waters have noted paranoia, anger and ontergenerational trauma, as well as lyrical interests in fascism and madness which he refers to as “the dark side of the moon” (“lunacy” assuming social as well as personal incarnations). This darkness is conflated with mortality and the Freudian “death drive”. Toxic levels of misanthropy and malicious pessimism can arise. These concepts provided title and themes for the best-selling 1973 Pink Floyd album, The Dark Side of the Moon. Though only 29 at the time of writing and recording, Mr Waters remains fixated and has re-recorded the work 50 years later.

Background: Originating in Swinging London, Pink Floyd turned from blues to psychedelic jams. Principal songwriter and band leader Syd Barrett succumbed to bipolar disorder; links to excessive intake of LSD. Waters was deeply disturbed by his friend’s mental collapse; a situation he also described as “an existential threat” to the band just as it was becoming successful, forcing him to take the lead.

Family details: Waters’ grandfather killed in World War 1. Father a Quaker, an ambulance driver and a pacifist. Mother an ardent atheist and Communist. Father signed up as a soldier in World War II after joining English Communist Party and feeling need to fight Nazism; died in battle when Waters aged five months. Adhering childhood narratives of fatal irony, ideology blurred with faith, and primal nature of war, business and politics. Waters’ later self-regard as an anti-fascist warrior became hypnotically entangled. Oppressive aesthetic traits have been identified by previous analysts in Pink Floyd’s The Wall (1979) and Animals (1977): shrill lyricism, overlong Wagnerian inclinations in the rock music genre.

Analysis: Patient’s decision to “reimagine” the 1973 release manifests his ongoing combative need for narrative control, arguably at expense of PF co-creators: R Wright (keyboards, vocals), N Mason (drums) and D Gilmour (guitar, vocals). Contested historical allegations of Waters’ general bullying, as well as undervaluing Wright’s melodic contributions on the war elegy Us and Them. Intense conflicts with Gilmour, a similarly acidic and assertive personality, who maintained legal ownership of the Pink Floyd brand after Waters’ departure in 1986. Gilmour’s hot-cold guitar sound recognised as critical to PF’s signature identity along with Waters’ lyrical vision; with Mason taking an avuncular and conciliatory position between their egos and the less aggressive Wright (now deceased).

The Dark Side of the Moon Redux heightens monologues from Waters that took a more submerged place in the original recording thanks to the influence of Gilmour. By turns raspy, conspiratorially threatening, and elegiac, Waters’ voice is symbolically performative, capitalising on his age to assert past and present works as a preview and review of his life. These story-time reflections veer from intensely emotional to overbearing and vaudevillian.

The original Dark Side was famed for its high-fidelity quadraphonic sound and spectacular live shows Waters referred to as “electric theatre”. Waters has maintained the cutting-edge sonics on Redux. Assisted by co-producer and multi-instrumentalist Guy Seyffert and studio musicians associated with Norah Jones, Beck and Thom Yorke, the music is slick and delivered with intent; electronic and jazz-pop nuances filter a repressed atmospheric soundscape. It is almost possible to say it sounds competitively perfect: defining an artistically ambitious, yet enervating and bleak answer to the earlier, vital work.

Mark Mordue

ROCK

Road

Alice Cooper

Ear Music

“I’m the master of madness / The sultan of surprise.” So says Alice Cooper, 75, giving himself an introduction on album opener I’m Alice – as if he needs one after a career spanning seven decades and 29 studio albums. That declarative lyric quoted above might have been true at the height of Cooper’s shock-rock fame in the mid-1970s with the release of the classic Welcome To My Nightmare, but what was once cutting-edge has long since become a blunt blade. Though still an undoubtedly entertaining live performer with a litany of hits to draw from, his studio albums have spent decades being non-events. Road, unfortunately, doesn’t change that trend. Despite injections of energy from his band (Dead Don’t Dance) and guest guitarist Tom Morello (of Rage Against The Machine and Audioslave) on White Line Frankenstein, Cooper’s gruff speak-singing grows old quickly. The vaudevillian campness of Welcome To The Show and the wholly unnecessary misogyny of Go Away and Big Boots, too, translate poorly. As far as subversive rock icons go, it seems you either die Frank Zappa or you live long enough to see yourself become Alice Cooper.

David James Young

FOLK/ROCK

At The Roadhouse

The Paper Kites

Wonderlick

The Paper Kites’ lullaby-esque Americana is very much an ensemble effort, despite the stewardship of tender-voiced singer/guitarist Sam Bentley. On this sixth album, the Melbourne band gilds its sleepy ballads with steel guitar, banjo, mandolin, harmonies and other warming touches. Fans of The Band and The Middle East will appreciate that lived-in group vibe, but At the Roadhouse feels overlong at 16 songs. Too many of these tracks unfold at a similar pace, making even the more elegant ones blend together at times. That also means that fairly slight departures stand out all the more: Black & Thunder proves darker and smokier in tone and instrumentation alike, while June’s Stolen Car gets pleasantly mussed by some fuzzy guitar strumming. Most striking of all, the richly appointed closer Darkness at My Door finishes with a burst of applause and then a gospel-style vocal reprise set to handclaps. It’s a gorgeous moment, and the album could have used more surprises like it.

Doug Wallen

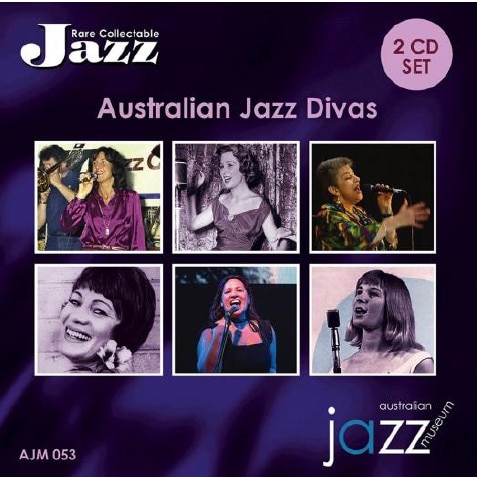

JAZZ

Australian Jazz Divas

Various Artists

Australian Jazz Museum

This double-album of 51 tracks featuring female Australian jazz singers continues the Australian Jazz Museum’s admirable work. Its first track, Des Tooley’s 1929 version of Am I Blue, sounds so good it might have been recorded yesterday. Our female jazz singers – from the red hot mommas who sang with trad bands through to the modernists who are still singing today – have been of a surprisingly high professional standard. Judith Durham and Beverley Sheehan were both products of Melbourne jazz, although Durham went on to fame via The Seekers, while her equally talented sister Sheehan enjoyed mere local artistic acceptance. The closer we get to today in the tracklist, the singing and arrangements become more sophisticated with the emergence of singers like Kerrie Biddell, Kate Ceberano and Grace Knight. With Janet Seidel, however, we are suddenly in another universe of musical excellence. Her stunning version of Lady Be Good, featuring the late Tom Baker, is the album’s highlight, and a reminder of the tremendous international success she enjoyed.

Eric Myers

ALTERNATIVE POP

Full Of Moon

Georgia Mooney

Nettwerk

As one-quarter of the group All Our Exes Live In Texas, Georgia Mooney has spent nearly a decade touring the world and crafting clever, vivid folk songs. Full of Moon has been a long time in the making, and it was stitched together in a fairly disconnected way: Mooney worked with US-based Noah Georgeson (Joanna Newsom, Devandra Banhart) and a string of musicians scattered across the world. It’s a testament to Mooney’s vision and musicianship that the resulting album sounds as united as it does: it’s nothing short of a triumph, a gorgeously sprawling collection of cinematic art pop that lovingly tips its hat to Kate Bush. Opener War Romance appropriately sets the stage, as Mooney’s voice cuts clean across the low swirl of the piano before being lifted by a lush mess of strings, synths, vocal harmonies and a blistering guitar solo. It’s completely enthralling. The softer moments are the highlights here: the spiralling guitars and strings that encase Mooney in I Am Not in a Hurry, and the tender closer Soothe You, which could have been beamed straight from a dimly lit bar in 1950s New York. Full of Moon is an album to savour and sink in to.

Jules LeFevre

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout