How teachers are re-educating boys brainwashed by Andrew Tate

As Andrew Tate awaits his fate in Romania, his mark on legions of teenage boys remains. Schools are now confronting his anti-woman manifesto with bespoke lessons.

Andrew Tate grew his brand online, racking up millions of young followers with his flashy lifestyle and version of “masculinity” while going unnoticed by most parents and teachers.

On Sunday the British influencer, who appeared on the celebrity television show Big Brother, is in a Romanian prison as part of an investigation into organised crime, rape and human trafficking.

As Tate, who denies the allegations, waits to find out what will happen next, the misogynistic philosophy he has built is still thriving among social media followers - and in the real world the effect has been significant.

The 36-year-old’s toxic views have become so endemic among teenagers that schools are putting on workshops and lessons to address them specifically and re-educate those corrupted online.

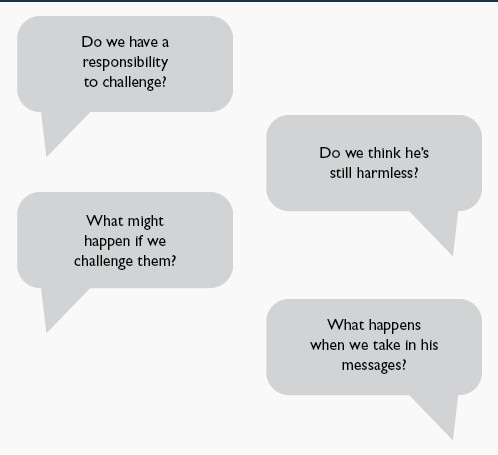

Questions asked of pupils include topics such as “Do we think he [Tate] is still harmless?” and “What happens when we take in his messages?”.

The presentation on Tate was given last term in a school in south London to a group of 14-year-olds after teachers noticed that pupils were parroting his sexist sentiments.

It was quickly derailed by an argument about rape.

About a third of the 30 students in the class passionately argued that women were responsible for their own sexual assaults, one of Tate’s top lines.

The male teacher asked pupils how they would feel if the victim were a female family member. “At that point a lot of the boys changed their tones when I put their mother or sister in that spot, but it was worrying that a few core kids didn’t and still said they would be to blame,” said the teacher, who asked to remain anonymous.

Misogynistic tropes continued to fly around the room. Some teenagers said that women were the property of men and that they should stay in the house or submit to their husband’s will. Tate, who was born in the United States before moving to Luton, Bedfordshire, amassed millions of followers through videos and podcasts shared prolifically across platforms such as TikTok, YouTube or Instagram.

In the clips he says that women belong in “the kitchen”, that they should be controlled with physical violence and are responsible for being victims of sexual assault.

Painting himself as a truth-teller and freedom fighter, he tells followers how to defend both themselves and him from pushback.

Teenagers have become so wrapped up in Tate’s ideologies that teachers are trying to fight back by providing alternative information and making them question the influencer’s beliefs.

“It is a version of radicalisation as far as I’m concerned,” says Sophie Whitehead, who works at the School of Sexuality Education, which provides workshops on consent.

“His rhetoric is so violent and it has affected so many young people.”

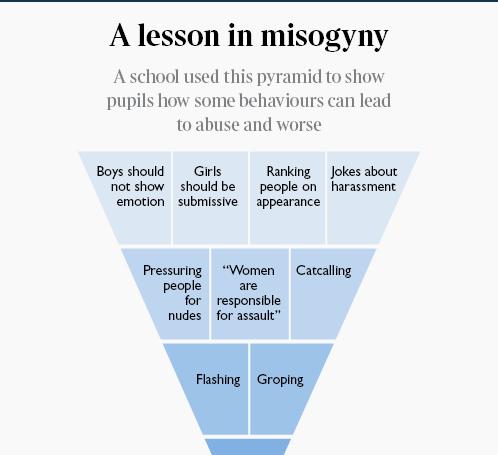

The south London teacher helped to explain the impact of Tate’s words by creating a pyramid, showing how some actions such as using violent words could escalate to criminal behaviour.

In the slide, pupils are shown that jokes about sexual harassment and violence or commenting on appearance can, at the extreme end of the scale, lead to flashing, coercive control or rape.

The teacher said that most of his students did not believe in Tate’s ideologies but he had been “blown away” by others’ views.

“They are genuinely nice kids,” he said, adding that a “cult-like” mentality had happened in pockets of teenagers, with some feeding their views to others.

A female teacher at another school said that some pupils were giving up on studying for exams, feeling that they no longer needed education to thrive.

“They [pupils] always end up saying, ‘I can get rich on the internet, that’s what Andrew Tate did’, she said. The son of a chess champion and catering assistant, Tate started working at his uncle’s fishmonger before later setting up a “camming” business, with his brother Tristan, in around 2015, which saw women perform acts on webcams.

He was arrested on suspicion of rape and physical abuse in the UK in 2015 and released under investigation. No charges were brought.

Tate appeared on Big Brother in 2016, still under investigation. He denied the claims and after four years the Crown Prosecution Service declined to bring charges.

It was last month that Tate was arrested, in relation to the new allegations, at his home in Romania, with Tristan as well as two women.

The Tates are alleged to have lured women to Romania before coercing them into performing pornographic content shared online.

In a preliminary ruling, the judge said that there was an “attitude of disregard towards women in general, which he only perceives as a means of obtaining large profits in an easy way”. They continue to deny the allegations.

In his online channels Tate gives instructions on how to get rich quick on the internet, putting on courses at his “Hustlers University” (pounds 39 a month) on trading cryptocurrency and drop shipping (trading goods before you own them). Alongside his “entrepreneurial” advice are extreme misogynistic views.

His initial attraction to young people, said one teacher, was often his advice around being confident and financially successful, and from there he capitalises on a post- MeToo anxiety with comments such as: “Females don’t have independent thought. They don’t come up with anything. They’re just empty vessels, waiting for someone to install the programming.”

Jay Jordan, a teacher in Dundee of five years, said the recent interest in Tate had made boys more hostile. “You used to have to deal with sexist stuff but now it is explicitly connected to Andrew Tate - the boys do not stop talking about him,” she said.

In one class she reprimanded a 14-year-old. “You’re just a woman,” he responded. Jordan, 37, said: “We’ve definitely gone backwards and it is worrying.”

Teachers and education leaders in the UK are dealing with the consequences of Tate’s videos, which have billions of views.

Rachael Warwick, chief executive of the Ridgway Education Trust, which runs three state schools in Oxfordshire, said that she was “very alarmed by Tate and the influence that his story may have”. Her trust is holding targeted lessons on the phenomenon.

Dr Gohar Khan, director of ethos at the trust, who has put together the classes, said: “Every school should be addressing the Tate issue. Up till last year I was wary about giving him airtime but pupils and staff have come to me and said, ‘Why are we not talking about this?’” Khan will “talk about why Tate has been in the news recently, for his arrest in Romania on charges of human trafficking and accusations of rape”.

“Our pupils are hearing all of this and I feel they need to hear it from what I think are reliable sources,” he added.

At assembly in the Oxfordshire schools, pupils are told about why expressions such as “man up” or “be a man” should not be used.

At St Dunstan’s, a co-educational fee-paying school in London, teachers try to have discussions about Tate and establish what pupils know before feeding teenagers more information. News articles about Tate are deconstructed with older pupils.

Warwick, from Ridgway, is a former president of the school leaders’ union, the Association of School and College Leaders. She plans to raise the influencer at the next national meeting, urging head teachers to run assemblies or lessons for boys.

Tate is also on the agenda within police forces, with some holding discussions. “The police are quite concerned about how it starts off with a few young kids watching these videos, then catcalling a woman, or girls in schools, then they are slapping girls’ behinds and then before you know it they are sexually assaulting people,” said an insider who attended such a session.

Yet despite Tate’s views, indicative of a wider misogynistic culture on the internet and sweeping through schools, there is still hope.

After the class about rape and harassment, the teacher in south London left feeling angry. Two students, however, gave him cause for optimism.

While initially arguing in favour of statements on the board, they changed their minds: “They actually had the courage to realise that they were wrong,” the teacher said. “You never change the mind of everyone all at once but you just pick them off one-by-one ... or maybe two-by-two.”

The Sunday Times