How Rudolph Giuliani went from hero to stooge

A man of unusual legal talents, he brought NYC back from the brink and could have led the US. What went wrong?

The arc of Rudolph Giuliani’s political career is best captured in two press conferences that bookended his role as a leading figure in US public life for more than two decades.

The first was the briefing he conducted on the evening of September 11, 2001. Here was the mayor of New York in the moment of his transfiguration into America’s Mayor, a battered but unbroken symbol of the city’s and the nation’s resilience, his clothes still dusted with pulverised remnants of the World Trade Centre.

He had spent all day overseeing emergency rescue efforts, comforting his fellow New Yorkers and coming to grips with the immensity of the horror, which he voiced in that memorable remark that the loss of life that day would be “more than we can bear”.

The second was on November 7, 2020, four days after the presidential election in which Joe Biden had defeated Donald Trump. As dignified as that solemn 9/11 event had been, this one had all the dignity of a drunken screaming match in a public lavatory on a Friday night.

Staged outside the Four Seasons Total Landscaping shopfront in suburban Philadelphia, down the block from a sex shop and across from a crematorium, it featured Giuliani and his fellow Trump supporters alleging widespread fraud by Democrats in an effort to steal the election.

The animated former mayor cited claim after claim of dead people voting and other abuses, each of which was easily debunked shortly after, even by Republican officials. Ridiculed as it was, the event set the tone for Trump’s long campaign of claims about the “stolen election” that continues today.

What happened to Rudolph Giuliani? How did he go from America’s Mayor to Trump’s bitch? How did a man of unusual legal and political talents end up a beached whale of a lawyer-politician touting for lucrative business in murky places and shilling for a discredited US president seemingly bent on up-ending the constitution?

A man who was once favoured to be president himself, now an object of widespread scorn, shunned by most of polite society and struggling to avoid prosecution.

It’s the essential question about Giuliani, but not one that Andrew Kirtzman, a former New York-based reporter who covered Giuliani’s mayoral campaigns and administrations closely, attempts to answer in this biography.

Instead, he in essence frames him as a dangerous extremist nutjob all along – from his days as a prosecutor of organised crime in New York in the 1980s through his time at City Hall to his brief presidential campaign and finally as a mouthpiece for Trump’s fabulism. Such a characterisation is hardly fair.

Giuliani was born in Brooklyn in 1944, the grandson of Italian immigrants. His bartender father, Harold, was a troubled, “pathologically aggressive” figure who spent time in prison.

The young, Democrat-voting Giuliani flirted with the priesthood but instead went to New York University to do a law degree, graduating cum laude. He was a clerk for a New York judge (who wrote a letter to the draft board sparing him Vietnam) and became an assistant US attorney with a reputation for tenacity.

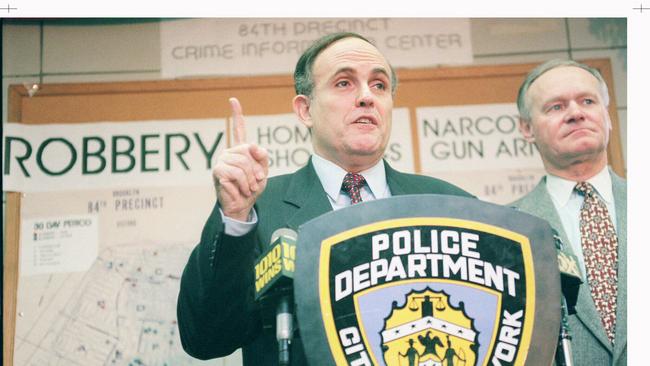

He joined the Republican Party in 1980 after Ronald Reagan was elected, served briefly in the administration and then returned to New York as a prosecutor, where he tackled the mafia and Wall Street corruption. In 1994 he was elected mayor.

As mayor of New York, Giuliani pursued policies that helped to reduce violent crime in the city by historic levels, turning it from the terrifying hellscape it was under his predecessor into one of the safest large cities in the US in just eight years.

Homicides fell from more than 2400 in 1993, the year before he took office, to just over 900 in 2001, the year he left. There are lots of plausible explanations for this drop – changing demographics, the fading of the crack epidemic — but almost every fair observer ascribes part of it to Giuliani’s tough-on-crime approach.

Owing to his stellar success in tackling crime and his globally acknowledged leadership after 9/11 (which earned him an honorary knighthood, among other gongs), Giuliani, at 57, seemed set for greater things when he left City Hall.

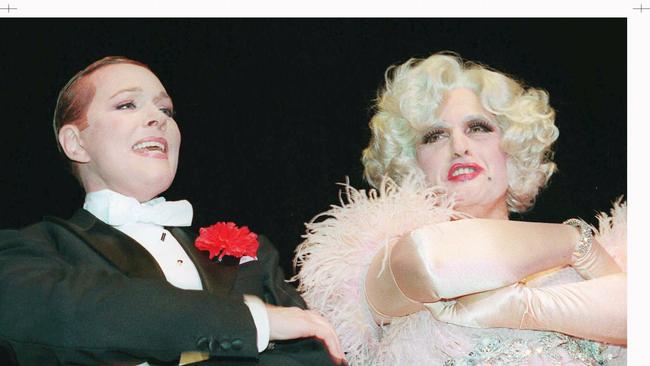

Yet it wasn’t to be. A planned run for the US Senate the year before, and a potentially riveting battle against Hillary Clinton, had already been dropped after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. More spectacularly, his bid for the Republican nomination for president in 2008 crashed in ignominy. Irony of ironies for a man who was, and is, the bete noir of progressives everywhere, it was his liberal stance on social issues such as abortion that doomed him with Republican primary voters.

And so America’s Mayor settled into a highly profitable life as a consultant. Kirtzman quotes Giuliani’s ex-wife as saying that at one point he was making a million dollars a month. It was never entirely clear what the firm did and it was hardly scrupulous in its selection of clients, doing business with assorted and would-be autocrats all over the world.

It was his relationship with Trump that proved to be most consequential for Giuliani – and perhaps most critical in his slide into ignominy. The two had known each other for many years when Trump ran for president in 2015. The former real-estate mogul and reality TV star had long been an admirer and, when he unexpectedly won the election in 2016, Giuliani was eager for a big job, preferably secretary of state.

Yet no formal role in the administration was forthcoming. Instead, Giuliani was a prominent adviser and supporter from the wings, always available to defend the president from the endless fusillade of media hostility.

That was why, in 2020, Giuliani threw himself into the prosecution of Trump’s “stolen election” narrative, resorting to ever more fanciful claims about fraud. The man who once put mafia bosses in jail and cleaned up New York’s streets now finds himself stripped of his law licence and facing prosecution in multiple jurisdictions over his efforts to overturn the election.

In his criticism of the former mayor, Kirtzman focuses on the sometimes legitimate civil liberties concerns that Giuliani’s tough policing raised.

There were several notorious examples of excessive use of force by police that called into question some of the tactics used. There is no question that minorities – young black people, in particular – felt unfairly targeted by preventive police measures.

However, you would have to be a partisan hack – or a New York City reporter – not to at least acknowledge that, in dealing with a city on the verge of social breakdown, there might be a trade-off between tough enforcement and the freedoms of its citizens.

By all accounts, Giuliani cuts a sad figure now, abandoned by former friends, drinking too much and unheeded by those who once hung on his every word.

Kirtzman offers one insight that might help to explain the arc of the man’s career: “Somewhere early in life, Giuliani developed a moral certitude that protected him from fear and self-doubt. He was infatuated with his sense of virtue, and viewed those who opposed him as either moronic or corrupt.”

It is ironic indeed that he ended up on the side of the moronic and the corrupt. But that shouldn’t be allowed to obscure the man’s many achievements.

Giuliani: The Rise and Tragic Fall of America’s Mayor, by Andrew Kirtzman (Simon & Schuster, 480pp)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout