How Queen Mary is modernising the Danish monarchy

In her first year on the throne the Australian-born queen has been a hit as she helps to bring the royal family into the 21st century.

It is a very familiar story: a young woman from a solidly respectable middle-class background falls in love with a prince.

Under the canny eye of a long-serving queen, she industriously moulds herself to the strictures of royal life, where her every word and choice of clothing are scrutinised for mistakes or hidden meanings. Gradually she wins the affection of the public.

And then one day the queen’s reign comes to a sudden end, leaving the princess as the living embodiment of the monarchy’s delicate modernisation after more than half a century of stability.

There are many parallels between the lives of the Princess of Wales and Mary Donaldson, but Queen Mary of Denmark, as she is now known, has achieved all these things on the other side of the planet to her home country.

Twelve months ago Queen Margrethe II, who had ruled the country since 1972, used her annual New Year’s Eve address to announce that she would become the first Danish monarch to voluntarily abdicate since Erik III almost 900 years earlier.

This came as a serious shock to many Danes, for whom the dry-witted and almost universally popular queen had become synonymous with the institution of the monarchy itself.

“I got very emotional,” said Malene Vandborg, 28, an IT project manager in Copenhagen. “I even started crying when I heard about it.”

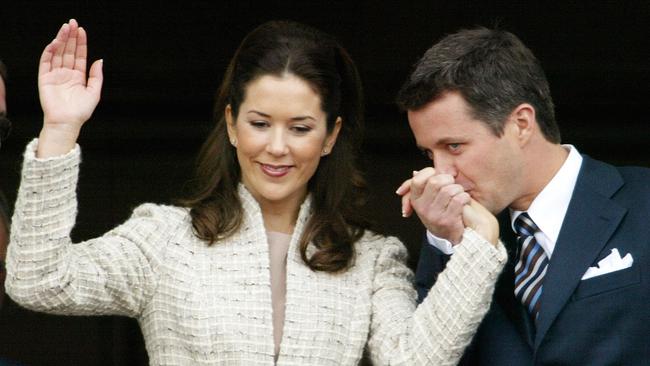

In January the throne passed to the crown prince Frederik, Margrethe’s oldest son, and Mary, his Australian-British wife, a marketing executive who had grown up in Tasmania and met her future husband at a pub in Sydney.

Some observers had reservations about the transition. Margrethe, 84, was a hard act to follow: eloquent, intellectual and dignified without being aloof.

Denmark is hardly a hotbed of republicanism: polls suggest barely one in seven people want the monarchy abolished. Yet it was not clear that Frederik, a former special forces frogman whose tastes run more towards football and distance running, could match his mother’s poise or adapt the institution to suit the expectations of a society that is less deferential today than it was 50 years ago.

“The newspapers used to write about the royal family in almost North Korean terms,” said Jakob Steen Olsen, the royal commentator for the Berlingske newspaper. “Now it’s possible for even a conservative paper like mine to be more critical. The old idea of ‘never complain, never explain’ is becoming more difficult.”

Olsen said that before the couple’s accession to the throne there had already been some questions about their judgment. They were seen as slow to cut ties with the shoe manufacturer Ecco, an official supplier to the royal family that had been heavily criticised for continuing to operate in Russia after the invasion of Ukraine.

Despite their vocal advocacy of children’s mental health, they also took a long time to withdraw Prince Christian, their eldest son and heir, from the elite Herlufsholm boarding school after a government report found it had been rife with abuse and bullying.

The most significant problem, though, was within the marriage itself. Weeks before Margrethe’s abdication, Frederik had been photographed paying a two-hour visit to the apartment of Genoveva Casanova, a Mexican socialite, in Madrid, giving rise to speculation that the royal union was on the rocks.

Rather than addressing the Casanova problem head on, Frederik, 56, and Mary, 52, have done so indirectly, stressing the value of family in their public statements and appearing together on a programme of royal tours.

They brought in an almost entirely new staff, led by the lord chamberlain Christian Schonau, a former senior civil servant. Early on, Schonau helped them to draw up the first public list of gifts that the monarchy was prepared to accept.

“He is seen as the strong man behind their strategy, the mastermind of changes in the royal approach,” Olsen said. “At last they are showing they realise that more transparency is needed.”

Since then Mary has emerged as the royal family’s strongest asset. Unusually, she is largely cast by protocol as the king’s equal, walking side-by-side with him rather than keeping the previously customary two steps behind.

With a fluent command of Denmark’s language and cultural idiosyncrasies, she is thought to write her own speeches. In October she made a successful solo trip to Brazil, providing the world’s glossy magazines with images of her bottle-feeding a baby manatee.

Opinion polls now suggest she has an approval rating as high as 86 per cent. “They know Mary is their best card to play. She’s extremely popular,” Olsen said. “They do complement each other in many ways. She gives him an edge that he lacks. He has given her a certain warmth.

“He is not very eloquent. She is better at saying what needs to be said. She is quite a control freak. These well-educated women who come into royal houses are often better at it. You get the impression of a much more professional, business-minded approach: seeing what the royals do as much less of a God-given mystery.”

There is a risk, however, that a more modern style of monarchy, built around relatability and campaigning on cuddly but politically charged issues such as decarbonisation and women’s rights, may alienate some of the couple’s more traditionally minded subjects.

The Victorian constitutional scholar Walter Bagehot once warned against letting in “daylight upon the magic” of royalty; a comparable proverb in Danish warns against brushing the dust off a butterfly’s wings.

For now, though, there is little evidence of public scepticism on the streets of Copenhagen. “I think [Mary] is definitely helping the royalty in Denmark to modernise, but still keep the needed distance,” said Niels, 68, a medical doctor who declined to give his surname.

“She’s transforming [the monarchy] in contrast to some of the other royal families in Europe. So I think she’s part of helping the royals, at least into the next generation. I mean: one never knows how royalties will develop in Europe.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout