How Hunter Biden became the hunted

Hunter Biden’s high level contacts opened doors until he entered Ukraine’s murky business world.

Led by Rudy Giuliani, President Trump’s pugnacious lawyer, old controversies have been revived over Hunter’s business dealings and what advantage, if any, he may have gained from his father’s office.

That no evidence of any corruption has surfaced has not stopped the hunt. Hunter’s business dealings have ranged from China to Ukraine, but of equal interest to the gossip pages is his messy private life, his struggles with drug and alcohol addiction, his divorce from his first wife and his relationship with Hallie, the widow of his late brother Beau - the elder, successful Biden son who it was hoped would one day run for president, but who died in 2015 aged 46 of brain cancer.

Hunter says his earliest memory was waking up in a hospital bed, aged two, to hear his brother whispering “I love you”, after the 1972 car crash that killed their mother and sister.

As a young man Hunter gave up a postgraduate degree in creative writing to go to law school. His first job, for MBNA America, a donor to his father’s Senate campaigns, raised the first questions of impropriety: at the same time he worked as his father’s deputy campaign manager. Hunter soon found the corporate atmosphere stifling and left to work for the Clinton administration, before joining a Washington lobbying firm.

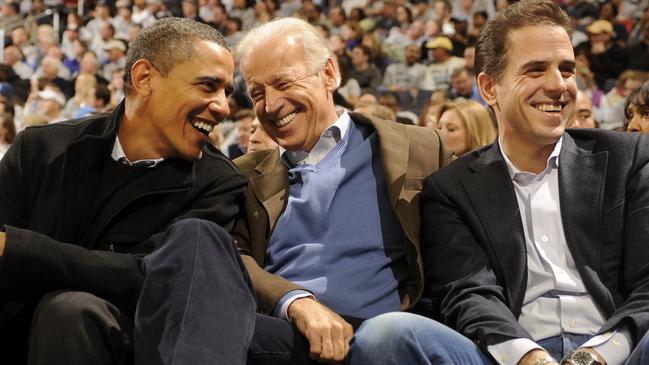

He and his father struck an agreement not to discuss business to avoid conflicts of interest, but that was unlikely to deter clients from believing they could leverage Hunter’s connections. In 2009, after Joe Biden became vice-president, Hunter went into business with Christopher Heinz, stepson of the senator John Kerry, creating a private equity firm. Critics claimed that it scored profitable deals with foreign governments after diplomatic missions by their powerful fathers. One that came under scrutiny was with the Bank of China, coinciding with a trip to China by Joe Biden on which he was accompanied by Hunter and Hunter’s daughter, Finnegan.

In 2014 Hunter joined the board of Burisma, a Ukrainian natural gas producer. He was to focus on the issue of corporate governance and corruption. His role coincided with his father’s oversight of US policy in Ukraine, including efforts to fight corruption.

Mr Trump’s allegations have centred on a claim that Joe Biden applied pressure on Kiev to fire Ukraine’s prosecutor-general, to stop him investigating Burisma and Hunter.

Throughout it all, Hunter had struggled with addiction, relapsing after seven years of sobriety in 2010. In 2014, he was discharged from the Naval reserve after a drugs test. He began drinking again after Beau’s death, ultimately ending his marriage and his hopes of a political career.

He remarried in May this year, having met his bride, a South African film-maker, a week earlier.

Analysis: Kiev corruption lies at heart of claims

Hunter Biden entered the murky world of Ukrainian business at a time when his father was trying to press a new government in Kiev to clean up its act or miss out on hundreds of millions of dollars of American aid.

He joined a Ukrainian natural gas company, Burisma Holdings, which was trying to smooth its reputation by recruiting a strong international board that included a former president of Poland. It was 2014 and Burisma was under investigation over allegations that its owner, Mykola Zlochevsky, had given government contracts to companies he controlled when he was minister of ecology.

Mr Zlochevsky was an ally of Viktor Yanukovych, who had been ousted from the presidency in February that year after failing to rein in corruption and sign an economic agreement with the European Union.

The Serious Fraud Office in the UK froze USA$23 million in accounts linked to Mr Zlochevsky, saying that they were connected to money-laundering. Ukrainian prosecutors accused him of embezzling public funds.

Burisma’s acquisition of board members with powerful contacts looked like an attempt to curry favour as it faced the potentially hostile Ukrainian authorities under the incoming pro-western president, Petro Poroshenko.

The younger Mr Biden’s readiness to engage with the company - and earn up to $50,000 a month as a board member - raised eyebrows in Washington, considering his father’s role.

The post-Soviet history of Ukraine is littered with the victims of battles between oligarchs, politicians and revolutionaries. Huge natural resources, billions of dollars in profits, weak institutions and shaky justice leave many businesses seeking any protection they can find.

While lamentable to many, the practice of US leaders’ relatives offering their services to those who hope for sway or shelter is nothing new. In 2001 a client of Hugh Rodham, Hillary Clinton’s brother, paid him $400,000 in the hope that he would lobby for a presidential pardon from Bill Clinton.

In Joe Biden’s case, the potential conflict of interest arises from his demand that Viktor Shokin, Ukraine’s prosecutor-general, be ousted. In 2016, Mr Biden has said, he told Ukrainian leaders they would not get a $1 billion loan guarantee unless they removed Mr Shokin. “I looked at them and said, ‘I’m leaving in six hours’, ” he said last year. ” ‘If the prosecutor is not fired, you’re not getting the money.’ Well, son of a bitch. He got fired.”

President Trump says Mr Biden’s demand was made because Mr Shokin was investigating Burisma and might have implicated his son. Mr Shokin has since said that he had been preparing to question Hunter Biden. However, according to Mr Shokin’s former deputy and other sources he did little to investigate Burisma, and by the time Mr Biden issued his ultimatum the case had long been dormant.

More significantly, Mr Biden’s call was part of a wider demand from western governments and international donors such as the International Monetary Fund to oust Mr Shokin as part of anti-corruption measures.

The case against Burisma was closed in 2017 after the company paid additional taxes, and Hunter Biden stuck with his post until April this year. He was never charged with any crime.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout