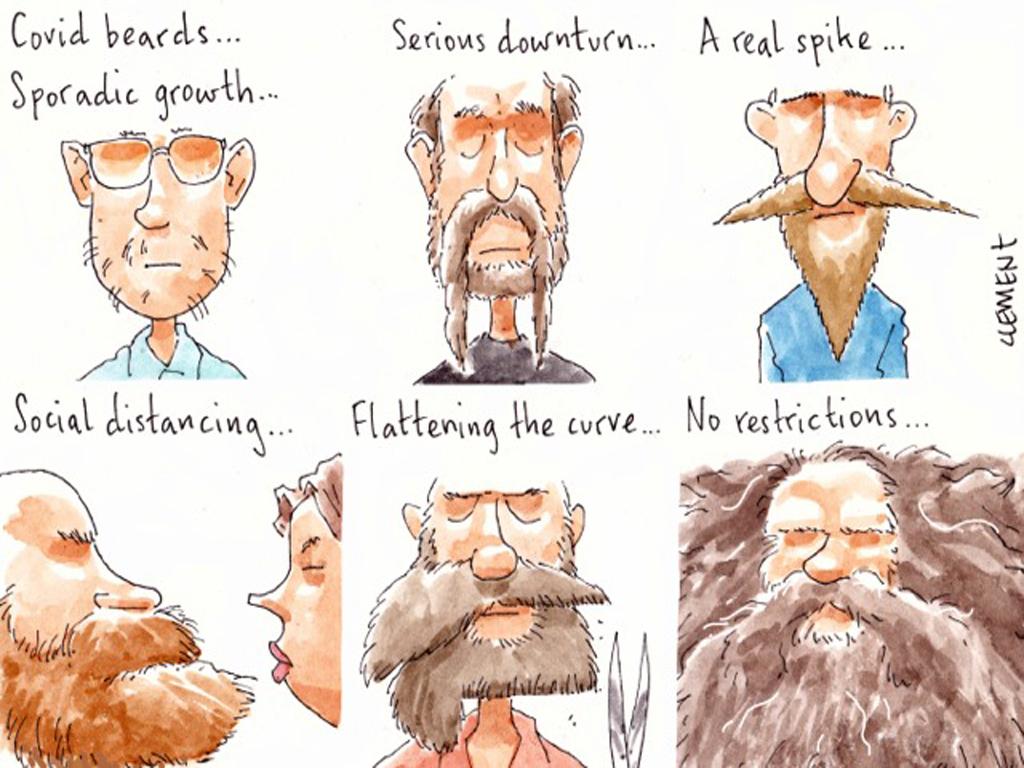

Hair apparent JD Vance could bring beards back to White House

If Donald Trump wins in November his running-mate would make history as the first vice-president to wear a full set of whiskers since 1933.

Introducing JD Vance at the Republican National Convention this week, his wife Usha told the story of how they met and fell in love as students at Yale Law School.

“The JD I knew then is the same JD you see today,” she said. “Except the beard of course.”

The Republican Party’s nominee for vice-president is regarded as an economic populist, an “America First” isolationist and as the heir apparent to Donald Trump. But if elected he could also bring about another change to the face of American politics.

Vance is poised to bring a beard back to the White House. The last vice-president with facial hair was Charles Curtis, who left office in 1933. And his was no more than a moustache. William Howard Taft, a native of Ohio who also studied at Yale, managed a term as president with a moustache, from 1908 until 1913. Benjamin Harrison, the last properly bearded commander-in-chief, also from Ohio, left office after a single term in 1893.

After Curtis, beards and moustache largely vanished from the faces of America’s leaders. Some connected this to class associations or to a deepening urban-rural divide: beards were for farm labourers and mountain men, not for presidents.

In a study conducted in 2007 and 2008, college students were shown photographs of pairs of congressman from the same party who looked rather like each other, except that one had a beard or moustache. The bearded politicians were presumed to have more masculine traits and to be less supportive of feminist issues.

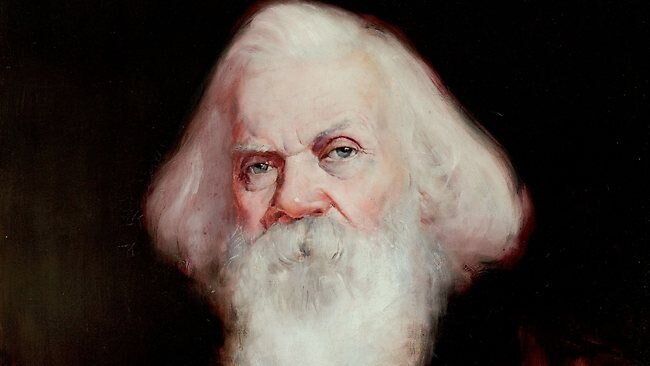

Such attitudes may have been fine during the Civil War and after it, when Rutherford B Hayes, a one-term president, sported a tremendous beard that obscured most of his neck. But with the advent of women’s suffrage, facial hair may have become more of a liability. In a paper based on the study of congressmen with beards, Rebekah Herrick, a professor of political science at Oklahoma State University, suggested that they could signal “strength and dominance” but could make a politician appear less compassionate.

If this made them less appealing to female voters, it also made them less appealing to Donald Trump, a long-time opponent of facial hair. In 2016, while considering candidates for secretary of state, he is said to have ruled out John Bolton because of his moustache. He managed to put aside his aversion two years later when he made Bolton his national security adviser.

Bolton told The Bulwark that Trump attempted to assure him that he did not mind the moustache during a meeting at Mar-a-Lago. Trump said: “Look, this moustache thing, well, my father had a moustache,” according to Bolton.

“That was like him saying, ‘Don’t worry about it,’” he said.

Trump’s reservations regarding facial hair remained, though. After his son Donald Trump Jr returned from a hunting trip with a beard, in 2018, his father apparently disapproved. “I don’t like it on you, as I’ve told you,” Trump said on his son’s podcast two years later. “I think that’s fine if you want to do it. I’m a libertarian in that way, you can do whatever you want. But I don’t like it on you.”

Vance, 39, a close friend of Don Jr, has sported a beard since his run for the Senate. Without it he was apparently liable to be mistaken for a teenager, though there was also speculation that it would scuttle his chances of being picked as Trump’s running-mate.

Trump, however, told Fox News that it would not. “He looks good,” he said. “Looks like a young Abraham Lincoln.”

It may also have helped Vance to pitch himself as a son of Appalachia, a region long associated with economic struggles, though his wife Usha also sought to temper any conclusions people might draw from his beard. The man she met at Yale was “a tough marine”, she said. But his “idea of a good time is playing with puppies … And watching the movie Babe.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout