Global vacuum heralds a big year for middle-ranking powers

The fact is, though, that war begets war and this is the one sure bet for 2023.

There will not only be more blood and gore on Ukrainian battlefields and in cities besieged by Russia, not only sharpening strategic competition between the US and China, but also the re-emergence of small and not-so-small wars elsewhere. These shouldn’t be ignored.

Vladimir Putin’s invasion pushed into the shadows the simmering row between Armenia and Azerbaijan, the fast-approaching death of the Iranian nuclear deal and the growing likelihood of Turkish forces attacking Syrian-based Kurds (clue: Turkey’s President Tayyip Erdogan is seeking re-election in June).

Now, they will soon be back on the agenda. The ceasefire between Tigrayan rebels and the Ethiopian government, agreed in November, also looks wobbly.

The fighting in Ukraine last year drew attention to Putin’s weakness but also raised fears that US President Joe Biden and his NATO allies were suffering from tunnel vision.

The central Asian states that were once considered Russia’s back yard noted that Putin’s attention was wavering and are beginning to reimagine their relationship with the Kremlin. Armenia, aligned with Russia, lost its 2020 war with Azerbaijan.

Putin pledged to keep the peace.

Now he has no credibility as a peacemaker.

Azerbaijan, which won its war by using Turkish drones, is looking even stronger.

The success of US weapons in tipping the battle against Russian forces was a great advertisement for American tech that hardly anyone can really afford.

It has highlighted the antiquity of Russian weaponry and tactics, but also underlined that Biden can probably take on only one scrap at a time. That is forcing a rethink, for example, in Saudi Arabia.

It is heavily dependent on US weaponry but is no longer sure whether an overextended White House would react strongly enough if Iran sprinted for a nuclear bomb.

And so it has started a cautious conversation at foreign ministerial level with Tehran, probably to see whether Iran would reduce its support for Houthi rebels in Yemen.

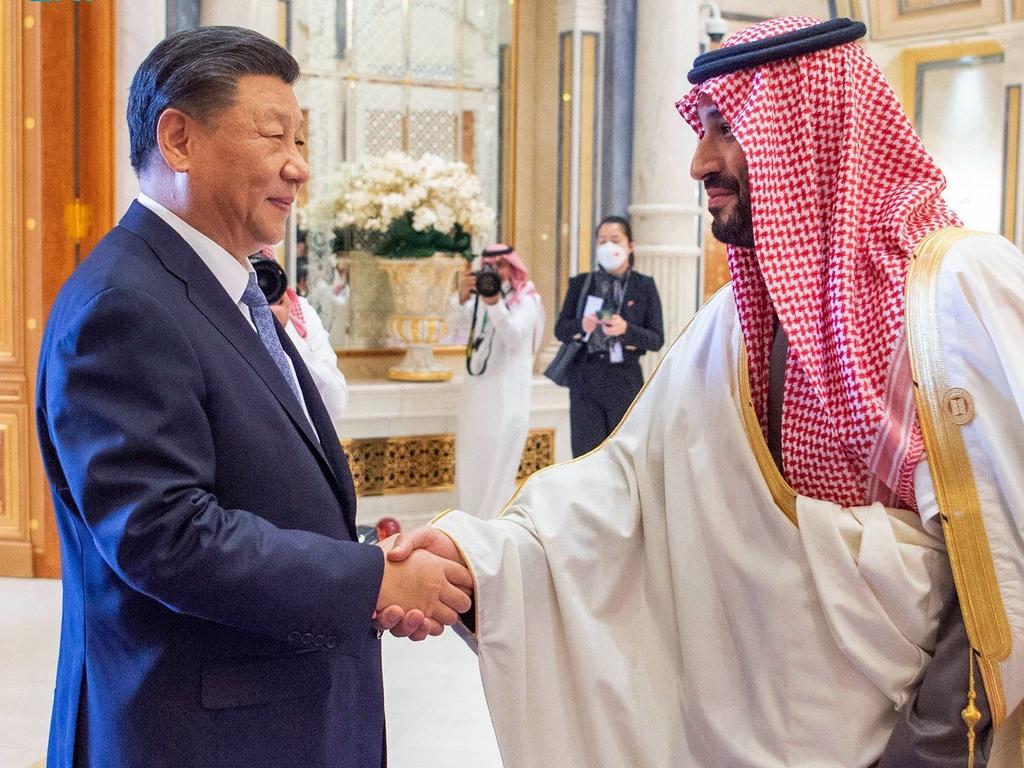

It talks to China about Beijing’s wish to pay for oil in the Chinese currency, in effect a petro-yuan. And like much of the global south there hasn’t been a squeak of protest about Putin’s war.

The effect of the 2022 invasion, then, has been to reshape geopolitics. The US and its NATO allies say the breaches in international law are so grave that the rest of the world should take a moral stance against what is, essentially, a colonial war of conquest.

I took some soundings on this from a politically awake Algerian who described the choice between supporting a US-backed Ukraine or a Russia with its own “legitimate” security concerns as zugzwang, an invidious move forced on a cornered chess player.

“Where was the West when our continent had our own wars?”

He pointed to the dreadful Tigrayan war between 2020 and 2022, which by some counts left 600,000 dead.

“What if we support Ukraine, and Biden strikes a deal with Russia? Do you think Putin will thank us for siding with the West? We’ll be left flapping in the wind.”

Similar voices can be heard across Africa and the Middle East. Their argument is that Russia makes an effort – its Wagner Group mercenaries are more ruthless and more effective in keeping central African regimes in power than their former colonial overseers.

Biden’s America is barely visible. As for China, it does not demand an explicit political price for its aid. Hence the enduring silence in the global south about the war in Europe. It will be no different, one suspects, if and when China moves on Taiwan.

What is happening instead is that pragmatic middle-ranking powers, in-betweeners such as Turkey, India and Azerbaijan, bankrollers like the Saudis and Qataris, are moving in to influence, to advise and invest, fill the great power vacuum.

They slide in their allegiances. Ignore them at your peril because they are the difference between isolating Putin diplomatically and allowing him to thrive, the back door for sanctions-busters who make a nonsense out of Biden’s promise to pit a unified democratic front against autocracies.

The big danger of 2023 emerges out of this world of ambiguity. Israel has always said it will not allow Iran to become a nuclear power because it poses an existential threat. And it would act, if necessary, without US approval.

This October marks the moment when the European Union supposedly acknowledges Iran’s progress towards restraining its nuclear program and starts to lift sanctions.

In fact Iran has been enriching uranium to a high degree, just below weapons grade. Israel’s new government is adamant the West should not “extend and pretend” – that is, ignore Iran’s violations of the 2015 deal in the hope of an eventual settlement.

Its instinct would be to, at the least, hit Iranian military depots in Syria to deter a threat from Tehran.

But here’s the rub: Russia controls Syria’s air space. It can close the skies to Israeli jets. The price of an attack could be a demand from Moscow (which uses Iranian drones in Ukraine) that Israel renounces any support for Kyiv.

Putin’s war has made toxic the whole geopolitical environment, across continents and polities. And it is ensuring that 2023 will be as full of jeopardy as the previous 12 months. Hang on tight.

The Times

New Year predictions, as The Economist magazine regularly discovers, are a mug’s game, especially when the world seems to be riding into a whirlwind.