George Floyd fallout: Black lives are slowly getting better but that only fuels anger and culture war

Unfulfilled expectations and the culture war between left and right over ‘systemic racism’ explain the George Floyd backlash

Hundreds of thousands of young men and women across America, locked down in home-quarantined ennui, had something to celebrate this northern spring.

Universities and colleges sent out their annual acceptance notifications to those who have finished high school, the reward for four years of effort and, in a climate of economic uncertainty, at least one sure step on the ladder of career opportunity.

Top of the wish list for many ambitious students is Harvard University, ranked number one in most surveys, which promises a glittering education and a well-trodden route to the best-paid jobs in America and the world.

For most candidates Harvard had disappointing news. The 400-year-old university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is the most competitive in the US and accepts fewer than 5 per cent of applicants. For nearly 300 young black men and women, though, many of them from disadvantaged neighbourhoods and families, there was joy.

Almost 15 per cent of Harvard’s admissions this year were black students. That’s a significantly higher proportion of black people going to Harvard than there are African-Americans in the US population. For the past 20 or more years the admission rate for black students at Harvard has been much higher than for whites or other ethnic groups.

All of the most prestigious colleges in America have been aggressively seeking to increase access to their halls for decades. Quality higher education is proven as the surest way to lift disadvantaged individuals and communities. Most top universities don’t have as high a proportion of African-Americans as Harvard but they have all dramatically increased their intake of black, as well as Latino, students.

Black lives improving

As the US is convulsed once again by racial tension in the wake of the May 25 killing of George Floyd, a 46-year-old black man, by a white police officer in Minneapolis, the plight of black people in America is under renewed scrutiny.

The protests and turmoil that have engulfed the country have been the largest and most disruptive since those that followed the murder of Dr Martin Luther King Jr in 1968. And they have prompted the question: how much has life improved, if at all, for African-Americans since those days that brought an explosive new urgency to the civil rights movement?

To the many hundreds of thousands of protesters, and to many more round the world, America is irredeemably racist and oppressive. Rooted in slavery and segregation, today’s America still systematically keeps black people down, crippling their lives and denying them opportunities for improvement.

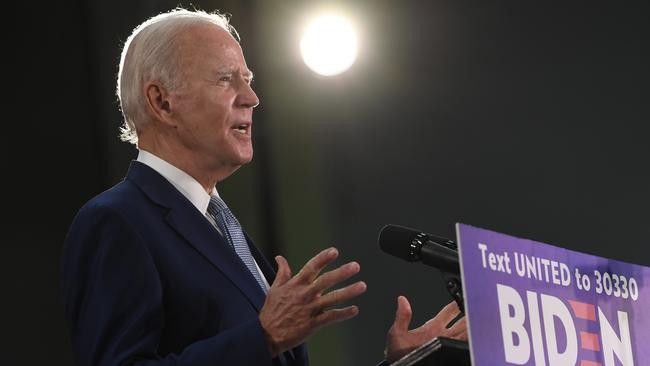

“The moment has come for our nation to deal with systemic racism, to deal with the growing economic inequity in our nation,” Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee for president, said last week. Few would challenge the idea that there remain wide inequalities in the US, and that African-Americans in particular lag behind white people in opportunity and resources.

But behind the tumult is a claim that, for all the efforts of the civil rights movement, for all the fissures revealed by those riots of 1968, life hasn’t fundamentally changed for black people.

That’s just not true. In fact, on virtually all measures, life has improved in the US in the past 50 years: not just in absolute terms but relative to white people. Inequality persists but advances have been widespread and significant, as those successful Harvard applicants demonstrate.

“To suggest that there has been no progress I think is foolhardy,” Harold Ford Jr, a black former Democratic congressman, told me. “That being said, I think it’s hard to deny some of the income numbers and the wealth numbers, and the ownership numbers in the country … So there are some things that do bear resemblance to 30, 40, 50 years ago”.

Economic and social indicators show evidence of real progress in the prospects for African-Americans. Part of the challenge in assessing this progress lies in isolating the condition of black people in the US over the past 50 years from the rapid growth in inequality across the nation and all ethnic groups.

White decline

In fact, in the past two decades, the condition of poor white people in smaller towns and cities across America has deteriorated, not in relative terms, but in absolute terms. A recent book by Anne Case and Angus Deaton, professors at Princeton University, Deaths of Despair, documented the extraordinary statistic that life expectancy for working-age white men without a college education is declining in the US for the first time since the government has been keeping records, driven by alcohol and drug addiction, suicide and the collapse of communities and family life.

But the plight of the white working class, which has surely played a significant role in domestic politics in the past four years, shouldn’t distract from the specific challenges that have confronted African-Americans. The riots of 1968 wrecked dozens of cities. Worst hit were the inner-city black communities in places such as Washington DC and Detroit, which took years to recover. In political terms the riots probably contributed significantly to Richard Nixon’s presidential win that November. But the social awakening, launched by the civil rights movement, did contribute to wide-ranging change, such as affirmative action in employment and education.

Some intangible but visible changes in the past half-century have elevated the status of black Americans: the acceptance of a long-unequal minority has been driven in part by symbolic advances. Black Americans have taken positions of prominence in government, business, sports, the arts, that were once deemed closed to them and, it should be noted, that still seem to be denied to minorities in many other countries around the world.

In the past few decades alone, two African-Americans have served on the Supreme Court. We have had the first black secretary of state (two, in fact), the first black top military officer, the first black astronauts, mayors of New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, the first black Playboy playmate of the year and US Masters golf champion; the first black chief executive of a Fortune 500 company, the first black governor of a southern state and the first black man from the former confederacy elected as a senator. And of course in 2008 Barack Obama became the first African-American to be elected — and serve two terms — as president.

These symbolic advances, which have done much to improve opportunity, to raise ambitions for African-Americans who were previously seen as prohibited from advancing, have tracked similar, halting progress in most metrics of social and economic condition of the minority.

A report in 2018 by the Economic Policy Institute looked at the condition of black Americans 50 years after the King riots, using official and unofficial data. It found overall a picture of progress but still wide inequalities with the white population. In education, widely seen as the best structural route out of deprivation, black people have perhaps made the most evident progress. In 1968 only 54 per cent of African-Americans aged 25 to 29 had completed high school. In 2018, that number was 92 per cent.

Fifty years ago blacks trailed whites by 20 percentage points in completing school. Now the gap is just 5 percentage points, with about 97 per cent of whites finishing high school. Many more African-Americans also graduate from college. In 1968, among 25 to 29-year-olds, fewer than 10 per cent had a college degree. By 2018 that figure had risen to almost 25 per cent. But the gap with white Americans, who now also graduate in much larger numbers, was barely changed.

Economic data tells a similar story: improvement but still a significant gap. Before the COVID-19 crisis hit, African-Americans had been enjoying the best jobs market ever. In February, the unemployment rate for black Americans stood at 5.8 per cent, the lowest figure on record. The figure for white Americans was lower still at 3.1 per cent. But this gap between black and white joblessness was at its lowest level in decades, and down from 8 percentage points 10 years ago during the great recession. In 1968 the unemployment rate for black people hovered around 7 per cent, though the US was at a different stage of the business cycle then and the rate would fall further over the next year.

Earnings have also risen in absolute terms and somewhat faster than for whites. Between 1968 and 2018, average hourly earnings for black workers increased by an average of 0.6 per cent a year, higher than the 0.2 per cent average for white workers. But the gap remains. In 2018, African-Americans earned on average just over 80 per cent of a white worker’s pay. That was up from 69 per cent in the 1980s.

About one-third (34.7 per cent) of African-Americans were living in officially defined poverty in 1968. Today, the share is just over one in five (21.4 per cent). That’s still much higher than for whites, for whom the share living in poverty was just under 9 per cent in 2016. Wealth levels have increased but again lag those of whites. While black families have increased their total wealth significantly since 1968, in 2016 the median black family had total assets of just a tenth of the median white family.

Basic social and health outcomes have also improved. African-Americans’ life expectancy at birth increased by 11.5 years between 1968 and 2018, faster than the increase for whites (up 7.5 years). That’s very close to white life expectancy. Black Americans are still incarcerated at about the same rate as whites but the total number for both has increased dramatically. For African-Americans the number is up from around 600 per 100,000 in 1968 to over 1,700 in 2016. As incarceration has risen, crime levels have fallen, though it’s been a mixed picture. Murder and other violent crimes rose strongly in the 1970s and 1980s but declined precipitously afterwards. In 1990 the homicide rate for blacks was almost 40 per 100,000 of the population, compared with just under 5 per 100,000 for whites. In the past few years the rate for blacks has been roughly steady at just under 20. For whites the number is now below 4. Meanwhile, black-on-black crime remains perhaps the largest single blight on African-American communities. In 2018 almost 3,000 black people were killed in the US. Eighty-nine per cent of them were murdered by other black Americans.

Overall, then, African-Americans have made strides in the past 50 years in absolute terms and, for the most part in narrowing the gap with whites. But the progress is slow and the gap still exists. Can this explain perhaps the explosion of anger that followed the killing of George Floyd?

Democrats’ shift to left

There’s an old theory that revolutions occur not when the condition of an oppressed group is at its lowest ebb, but when it has been improving, although not fast enough to meet elevated expectations. It’s possible that the expectations raised, especially by Obama’s election, might have helped produce frustration. There may be something of this in the US today.

But there may be another factor behind this week’s turbulence. The intensity of the protests suggests this fits into a wider political context that is reshaping the politics of the West. Of course there is genuine anger at scandals such as Mr Floyd’s killing and the failure of America to create a more level playing field for all its citizens. And of course the long shameful legacy of slavery can never be eradicated from the modern nation, especially one that remains unequal in so many ways.

But the vehemence of the demonstrations also comes at a time when the Democratic Party, the repository of political hopes of most African-Americans, minority groups and others for whom identity has come to define their political philosophy, has shifted decisively to the left. It was striking this week to hear even an old hand like Biden, and other experienced Washington centrists, sign up to the strictures of radical elements behind the protests. Biden’s talk of systemic racism is notable — it’s the language of a much more assertive left wing of the party that wants, among other things, reparations for slavery and, in most extreme cases, measures to take funding from local police forces and replace them with social programs.

This radical left has been energised by Donald Trump and the Republican Party. For their part, the Trump Republicans represent a new, similarly harder political movement: authoritarian and nationist — on display last week from the President himself, who has eschewed language of healing and focused on hammering the protesters.

The way in which anger over Floyd has caught on in cities like London and Paris is a sign that this is about a larger political struggle than the plight of black people in America. All this is perhaps further proof of the strains eroding the West’s liberal order. Angry with the excesses of capitalism and globalisation, the left is congealing around cultural and identity politics that seek to compel submission to the prevailing nostrums about “systemic racism” (as well as sexism). The right has rejected the untrammelled global mobility that conservatives such as Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher created in favour of a nationalist, authoritarian order of a more 19th than 21st-century hue.

Whatever progress black Americans have made in the past 50 years, and however much they still lag America’s whites, the larger cultural fight over race and identity is now rooted in the political struggle of our age.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout