Gen Z women join Australia’s mines for $200k salaries and TikTok fame

The hours are long, the work is hard and the heat is unrelenting yet the number of females working in the sector is growing because of the perks.

Hordes of fly in, fly out workers in high-vis vests and boots trudge into Perth airport most mornings to catch early flights to the iron ore and copper mines in the Pilbara, two hours north.

Until recently this 1600km commute – flying to the West Australian outback and back weeks later – was the preserve of men. No longer.

Young women are signing up in record numbers to toil away in the red dirt and 40C heat, lured by six-figure salaries and, in some cases, the chance to boost their profile on social media.

They are also answering the call in Queensland.

“The money is bloody awesome,” said Sienna Mallon, 27, who earns $200,000 a year as the site manager at a coalmine in central Queensland.

Beneath the rock of the outback lie some of the world’s largest deposits of coal, iron ore, lithium, gold and other minerals.

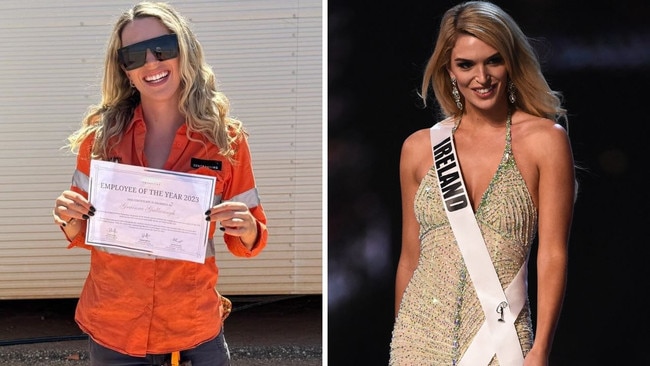

Ms Mallon, an agricultural science graduate, describes herself as the “poster child” for young women in the industry, having amassed more than 174,000 followers on TikTok. Brands such as gym supplements pay her extra to plug their products. Other TikTokers include Grainne Gallanagh, 30, a former nurse who was crowned Miss Universe Ireland in 2018, but made an unlikely career move last year to become a FIFO truck driver in the West Australian outback. Her light-hearted videos include advice about how to keep hair healthy in the desert, as well as complaints about the flies.

Although the big mining corporations frown on influencers revealing too much – forcing many to avoid naming their employer – they are keen to change the profile of their workforce, and recognise the power of social media to do so.

There are more than 100,000 FIFO workers across Australia, with most experienced employees on about $170,000 a year, plus a 15 per cent annual bonus. Many hope to save enough to get on the property ladder.

But it is not easy money. FIFO employees work gruelling 12-hour days, with regular night shifts, and live in large makeshift villages a bus ride from the mine sites.

Many young male miners have gained a reputation for becoming trapped in FIFO jobs to pay off their debts after squandering money on drink, drugs, gambling and prostitutes.

The industry’s reputation was severely damaged in 2022 by the findings of a state parliamentary inquiry into allegations of sexual harassment, rape, bullying and sexism fuelled by a hard-drinking culture in the mining villages.

Its report, Enough is Enough, concluded that mining bosses were either not recognising the need to curb such behaviour or not doing enough about it.

The report fuelled the drive to hire more women, who make up just 21 per cent of employees.

BHP, the world’s largest mining company, has set a target of achieving “gender balance”, whereby at least 40 per cent of its employees are women, by next year.

Its giant South Flank iron ore mine in the Pilbara, which opened in 2021 and has already met that quota, has been hailed as one of the most gender-diverse in the world.

As Ms Mallon, the miner, says: “It is a good time to be a woman in mining.”

The Sunday Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout