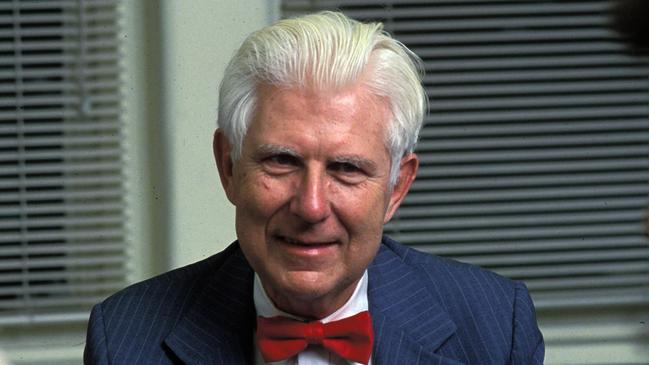

Father of cognitive behavioural therapy Aaron Beck gave me a reason to live

The American psychiatrist Aaron Beck died on Monday at the age of 100. I never met him, and he will have never heard of me, but he saved my life.

Sadness is intrinsic to the human condition. Everyone experiences the disappointment of thwarted ambitions, the pain of rejection, or the grief of bereavement. Some, such as my friends who survived the genocide of their communities in Bosnia, have known scarcely imaginable horror. But nothing I’ve known, in a comfortable life in a free society, compares in sheer misery to clinical depression.

Even before the pandemic, the World Health Organisation estimated that almost 300 million people globally were living with this illness. Depression is not just low mood but a psychiatric condition defined by its symptoms: above all, an overwhelming sense of guilt that permits no moment of relief, and constant thoughts of death.

It is likely that the incidence of depressive disorder will rise sharply owing to long Covid and the collateral effects of prolonged enforced isolation.

There is a clinically validated treatment for this condition. It’s known as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT).

The originator of this technique, the American psychiatrist Aaron Beck, died on Monday at the age of 100. I never met him, and he will have never heard of me, but he saved my life. I owe him more than I can say.

Until the 1950s, and the first generation of antidepressants, there was no clinically validated treatment for depressive disorder. Talking therapies were influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud, who hypothesised that mental disorders could be resolved by exploring long-buried memories.

The evidence that this sort of mutual exploration by therapist and patient, even in its more limited modern form, can cure disorder is thin. Beck put therapy instead on a scientific footing. He found out what worked and put it into practice.

The essence of Beck’s approach was that feelings are affected by thoughts. If something sad happens in our lives to cause mental turmoil, it is not the event itself that causes disorder but the interpretation we put on it.

The remedy is not to explore distant memories but to train the mind to interrogate destructive ways of thinking against the available evidence.

Everyone’s experience of depressive disorder is different but there are recognisable themes. Mine, as I entered middle age, lasted a full calendar year in severe form and then persisted for a while longer.

I could scarcely get out of bed or leave the house. My short-term memory was wiped out and I could scarcely write half a dozen words in a day. All I could think of, on and on, was how I craved death.

What had brought me to this state was not any great suffering but the weight that I placed on my setbacks: marital break-up, romantic disappointment, and the vast lacunae in my abilities as a father and a son. As I surveyed what I believed to be the wreckage of life, I was convinced not only of my frailties but of my irredeemable wickedness. I was lucky to find professional help. In addition to medication, I had the type of therapy that Beck devised. I saw a clinical psychologist, Dr Annemarie O’Connor, regularly. She had extensive training and a sympathetic personality, which reassured me, but CBT does not require initials after a practitioner’s name or even a human interface to be effective (it can be done online).

O’Connor made no attempt to delve into my early life. Instead, I recounted the thoughts and fears that had come to dominate my life. In the words of the 17th-century writer Robert Burton, in his work The Anatomy of Melancholy: “ ’Tis my sole plague to be alone,/ I am a beast, a monster grown …”

I was convinced of my depravity, and it led me to what is commonly known (though it isn’t a medical term) as a mental breakdown. To my wild imaginings, O’Connor simply suggested how the world could be interpreted even slightly differently, in a way that avoided interpreting every failing and disappointment as if it were catastrophic.

This is how CBT works. Beck explained: “At times, we (therapists) find a person’s reactions to an event are completely inappropriate or so excessive as to be abnormal. When we question him, we often find he has misinterpreted the situation.” So it was with me.

It would have made no sense just to tell me I was wrong. But a course of talking therapy showed me that the world was a less forbidding landscape than I had imagined, and that I still could create a purpose within it.

Whenever I feel sadness and regret, I think back to that turmoil and recall that, for all my failings, these are not the end of the story. Aaron Beck changed my life, by teaching me how to think again.

The Times

Oliver Kamm’s book Mending the Mind: The Art and Science of Overcoming Clinical Depression is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout