Drug-fuelled artists fly high but then sink low

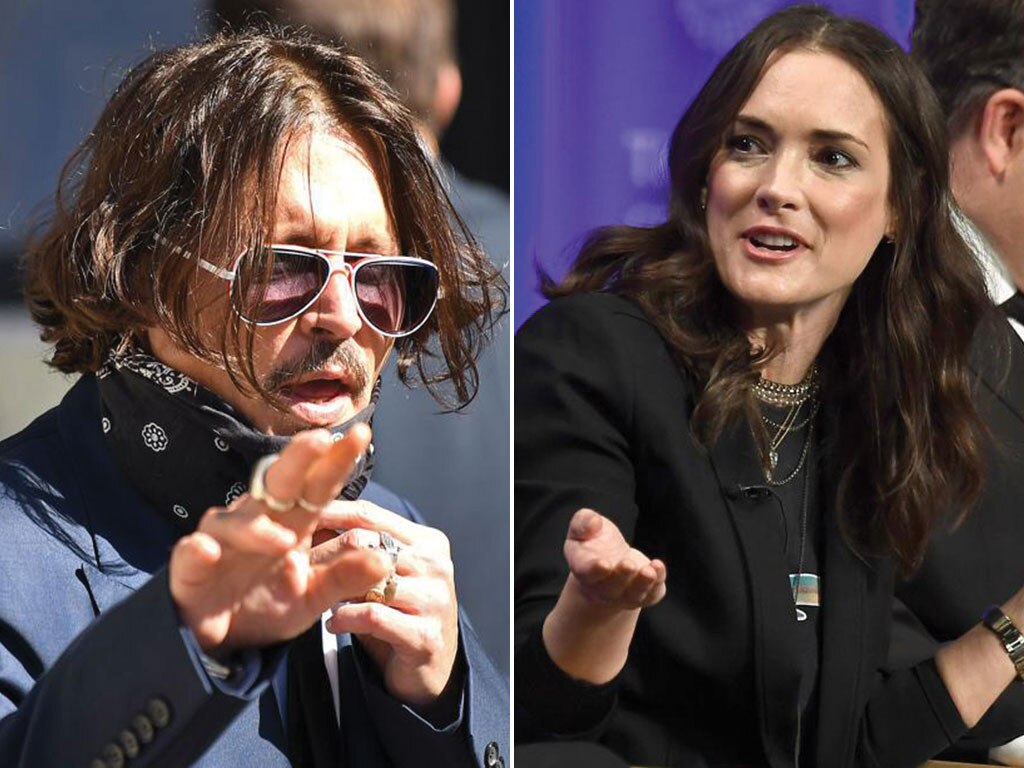

During his libel case against The Sun newspaper, the American actor reeled off a list of “literary heroes” who also happened to be druggies: Hunter S Thompson (Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas), Thomas De Quincey (Confessions of an English Opium-Eater) and Geoffrey Chaucer, “who was an opium addict”, Depp declared.

Now that is libellous. The great 14th-century poet was certainly aware of drugs. In The Reeve’s Tale he refers to a medieval menage a trois in which the participants “needed no dwale”, a narcotic potion made from belladonna or deadly nightshade. In The Knight’s Tale, the jailer is fed a cocktail of sweet, spiced wine laced “with nercotikes and opie of Thebes fyn” (narcotics and pure opium of Thebes), to knock him out.

But if merely referring to drugs makes Chaucer an opium addict, then Homer, Virgil and Shakespeare were also junkies. Othello was no stranger to “the drowsy syrups of the world”. Sherlock Holmes injected a “7 per cent solution of cocaine” but it has never been alleged that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a cokehead.

Depp’s confusion may arise from having taken drugs with fellow actor Paul Bettany, who played Chaucer in the 2001 film, A Knight’s Tale. These literary links can get confusing if, as Depp told the court last week, you have “taken every drug known to man” by the age of 14.

Claiming Chaucer as a fellow drug user is Depp’s way of suggesting that creativity and narcotics are connected, and that drugs are among the accepted tools of an artist’s trade — an attitude that has become embedded in our culture.

The romantic poets were frequently out of their heads. Shelley took laudanum to dull his raging headaches, Keats used it as a painkiller and Byron favoured an opium-based concoction called Kendal Black Drop as a tranquilliser. Even Jane Austen’s prim mother, who otherwise had little in common with Johnny Depp, recommended opium for travel sickness.

There is no record of Wordsworth getting off his face but Coleridge’s poem, Kubla Khan, was composed in 1797 after an opium-influenced dream.

If he wanted to find historically significant users, Depp would not have to look far: Thomas Jefferson cultivated opium poppies on his plantation, George Washington grew pot for his own medicinal use and Queen Victoria is said to have used it for menstrual cramps.

Drug takers have often sought literary precedent. De Quincey claimed in his 1821 work that in Paradise Lost Milton described how archangels had introduced laudanum into the Garden of Eden, and that Adam “fortifies his fleshly spirits” and “from the well of life three drops instill’d”. According to this theory, the first man in creation was also the first man to get stoned in the garden because the angels told him to.

But are drugs really a catalyst for creativity, providing powerful and unique insights? Hunter S Thompson insisted they were. “I’d hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence or insanity to anyone,” he said, “but they’ve always worked for me.”

Certainly, drugs have produced some great works, from the Beatles’ experiments with LSD to Allen Ginsberg’s poem, Howl. Wilkie Collins, an opium addict who was said to consume enough laudanum in a single dose to kill a dozen men, wrote The Moonstone, the first detective novel, under the influence. Aldous Huxley thought mescaline might open the “doors of perception to greater spiritual awareness” — and inspired Jim Morrison’s band, the Doors.

But for many, the temporarily altered mind produces only ephemeral creativity. As Arthur Koestler wrote after a session on magic mushrooms: “I solved the secret of the universe last night, but this morning I forgot what it was.” Paul McCartney conceded that writing well was impossible while “off our heads all the time”.

Recent studies suggest that instead of fuelling their genius, writers famously associated with booze and drugs produced better work without them. Ernest Hemingway, an alcoholic, and opium-addicted French poet Charles Baudelaire were most productive during periods of sobriety. Rather than firing the imagination, it seems that emotionally febrile writers are simply more likely to turn to substance abuse.

“Turn on, tune in, drop out,” if you still must. But please, don’t write about it.

THE TIMES

In the long, grim history of Hollywood hell-raising and drug-taking, Johnny Depp is surely the first to call Geoffrey Chaucer as a witness for the defence.