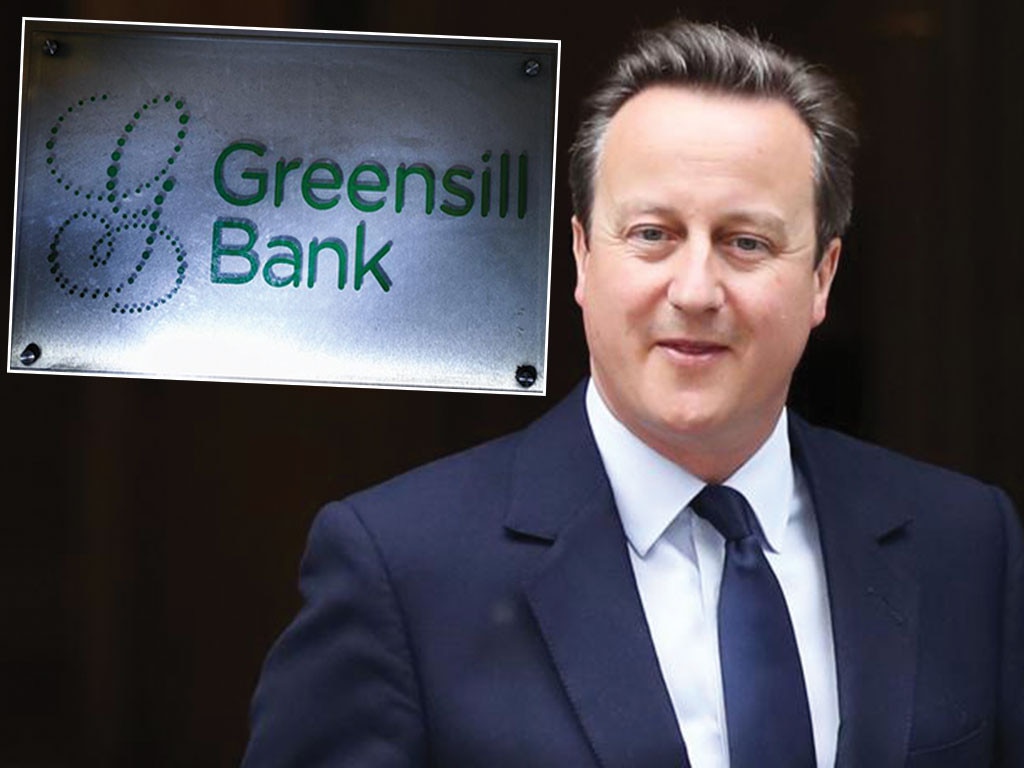

David Cameron spent two months browbeating UK treasury officials for Greensill

By piling pressure on the chancellor and Treasury mandarins, the former British PM engineered nine meetings over Greensill.

David Cameron resigned as prime minister of the United Kingdom and left No 10 in July 2016. But when the pandemic tore through Downing Street almost four years later, it was as if he had never been away.

On April 3 last year, as Boris Johnson was in quarantine, Cameron emailed an old colleague in Downing Street with an extraordinary demand. He explained that the chancellor’s emergency loan scheme to help big businesses, in its present form, seemed “nuts”. The former prime minister told an ex-aide: “What we need most is for Rishi [Sunak] to have a good look at this and ask officials to find a way of making it work.”

Cameron wanted the program redesigned to include Greensill Capital, a privately owned financial services firm that was in trouble. Having met its founder – Lex Greensill, the son of Australian farmers – while in No 10, Cameron was working as an adviser to the company. He held share options worth tens of millions of pounds. A personal fortune was on the line.

The Treasury had written to Greensill that day rejecting the idea of giving the company special help: the Covid corporate financing facility (CCFF) was a way for the state to lend money to blue-chip companies, not to a financial services start-up. Charles Roxburgh, the Treasury’s second most senior official, spoke for Sunak, having “obtained a view” directly from the chancellor. The conclusion was firm: “We cannot consider your request further.”

However, Cameron would not take no for an answer. He began a lobbying campaign that soon secured Greensill special access to the Treasury’s most senior officials. The financier was able to pitch his ideas and exert his charms at the highest levels of government for months.

Greensill Capital later became an accredited lender under a separate scheme, granting taxpayer-backed loans worth almost half a billion pounds.

A year on, Greensill Capital is in administration, having imploded under the weight of its debts. Cameron’s share options are worthless. The company’s collapse threatens 55,000 jobs globally, including 5000 in Britain. Johnson has not ruled out bailing out Britain’s third biggest steel business, Liberty, which faces bankruptcy as a direct consequence of Greensill’s disintegration.

Questions for Cameron

For these reasons the list of questions about Cameron’s conduct keeps growing. Was it proper for the former prime minister to lobby ex-colleagues directly on behalf of a toxic firm in which he had a financial interest? How was a private citizen able to bend Whitehall to his will?

Cameron has refused to comment on the affair. A “friend” suggested on Friday that he regretted texting the chancellor. But on Sunday, emails leaked to The Sunday Times reveal in Cameron’s own words further attempts to lobby insiders. They also pose questions for the chancellor.

It all began at 2.23pm on April 3, 11 days after the start of the first UK lockdown, when Roxburgh sent his rejection letter to Greensill, saying helping his company would create an unhelpful “precedent” for the Treasury. The department’s scepticism made sense.

The CCFF scheme was designed to give temporary taxpayer-funded loans to the biggest companies in Britain: retailers, construction giants and manufacturers that, in their own right, were deemed to make a big contribution to the economy and had to be saved at all costs.

Greensill, a plucky finance start-up, wanted to do something entirely different: use taxpayers’ money to issue its own loans to small and medium businesses left vulnerable to late payments or a lack of cash by the pandemic.

Sunak was not unsympathetic to such concerns; the Treasury, though, was designing other schemes to address them. To give Greensill a role under CCFF, the Bank of England would have to change its “market notice” – the rules set for the financing scheme.

Cameron was undeterred. His first port of call was an impressive young MP who entered parliament in 2015, only to disappoint him by backing Brexit the next year: Sunak himself. Perhaps the chancellor would have better news for his old master now. Cameron texted him asking to talk. The response was polite: “I am stuck back to back on calls but will try you later this evening and if it gets too late, first thing tomorrow (Monday).”

Cameron looked elsewhere. He contacted two MPs who had served under him and were now ministers in Sunak’s team, John Glen and Jesse Norman.

He also rang Sheridan Westlake, a veteran special adviser whose No 10 career encompassed Cameron, May and Johnson’s tenures, and whose focus, business, made him the ideal contact for the moment. He got through and the pair spoke.

At 5.28pm, Cameron sent a follow-up email, telling Westlake it was “great to talk” and putting his cards on the table, saying he needed to “find a way of making it work”. The former prime minister added: “It seems nuts to exclude supply chain finance [Greensill’s speciality]. We all know that the banks will struggle to get these loans out the door – and so other methods of extending credit to firms become even more important.”

Cameron attached a detailed list of bullet points outlining what Greensill wanted and why, explaining that the company had the “scale, technology, UK-based staff and capability” to make a real difference.

They at once exhibited confidence and desperation, with one stating: “Surely HMG [Her Majesty’s government] should be seen to be supporting UK Fintechs [financial technology groups].”

There was also a warning: failure to help Greensill would “almost certainly” mean that businesses across the country would not get the help they needed.

Cameron signed off the memo: “All good wishes, DC.”

Treasury changed stance after ex-PM’s lobbying

Like many ideas put forward by Greensill, who liked to speak about “democratising finance”, it was never said explicitly who the real winners were likely to be: not the taxpayer or business people but his own company.

There was scant mention of the company’s core business model either: paying a company’s invoices upfront in exchange for a fee.

In any case, the official is understood to have forwarded Cameron’s request to the Treasury. What happened next is unclear. But within days of Cameron’s lobbying, the Treasury’s outright “no” suddenly turned into a “maybe”. Even though Johnson was now in intensive care with coronavirus, and his ministers were grappling with the biggest postwar crisis, Sunak’s officials were made to find the time to hold Zoom meetings with Greensill to hear more about its ideas.

On April 7, Tom Scholar, the Treasury permanent secretary, and Roxburgh held a virtual meeting with Greensill representatives, who “had been thinking hard about how they could propose something that fits with the purpose of the CCFF” and would not require the market notice to be changed. If the official view was that their original plan did not work, then the Australian financier would happily work up something else that did.

The Treasury considered Greensill’s revised ideas and appeared willing to be flexible. On April 15, Roxburgh wrote saying Greensill’s tweaked plan still “doesn’t address our central problem” – but that an alternative he had proposed on the phone might work. “We and the Bank [of England] would be happy to discuss the details of this approach and could move ahead quickly on this basis.”

Civil servants felt obliged to listen to Greensill

It is unclear exactly what alternatives were explored: the Treasury says releasing information would compromise future policy-making. But it has released enough to show that officials felt torn: they were sceptical but felt obliged to listen to Greensill’s proposals.

On April 16, for instance, Greensill requested another call to discuss his “important and urgent” proposals. Roxburgh said yes. Minutes of the conversation state: “You were clear that we were in listening mode.” He also committed to “take [Greensill’s] points away and consider them”.

Sunak appears to have felt similarly, making clear that Cameron’s friends would get a special hearing and the Treasury would exhaust all possibilities but not wanting to overreach. He texted the former PM on April 23: “I have pushed the team to explore an alternative with the Bank [of England] that might work. No guarantees, but the Bank are currently looking at it and Charles should be in touch. Best, Rishi.”

Good news followed 24 hours after Sunak’s texts: Roxburgh, in the third of nine meetings with Greensill, said the government would do some “confidential” research with trusted banks and businesses to see if its revised proposals might work. Greensill said the company was “very pleased to hear this news”.

Over this period, Greensill enjoyed access to officials, in some instances receiving responses within ten minutes.

Nevertheless, it became apparent that the company’s proposals were as inappropriate as they had first appeared. The Treasury had already published information about the scheme: a sudden change letting Greensill take part would seem suspicious and potentially present legal issues. Sunak’s officials also feared that the proposals were too complicated and not guaranteed to put money in the pocket of business owners. Minutes from a call on May 14 state that Roxburgh spoke to Greensill “at the chancellor’s request”. The official asked “simple questions” but the idea “sounded complicated”, with minutes adding: “The government’s schemes were subject to intense media, parliamentary and public scrutiny.”

On May 18, Sunak signed off what seemed another definitive no: officials wrote to Greensill saying they were not redesigning their scheme because its proposal “would not bring sufficient benefits” to small businesses.

Yet even then Greensill, with Cameron in the background, kept on coming back. On June 11, Roxburgh told Greensill he was “still considering matters”.

Only on June 26, two and a half months after Cameron’s text to Sunak, did the Treasury finally give up, with Roxburgh saying he had “genuinely put in a lot of time” to explore Greensill’s ideas but, on CCFF, had run out of road. Greensill wrote saying he was “embarrassed” by his initial oversights and had come up with a “simple and elegant solution”, but the government’s view does not appear to have changed. It was not possible to use Greensill as an intermediary for small businesses in a loan scheme designed to help big companies. The idea, in short, did not make sense.

As administrators wind up what is left of Greensill’s empire, questions remain about how the company was able to get so close to the public sector, securing, between 2018 and last month, contracts to pay NHS pharmacies and staff and also become an accredited lender under another Sunak scheme, the coronavirus large business interruption loan scheme. The government has been asked to explain how Greensill was able to lend £400m ($720m) in taxpayer-backed money to one steel empire under that scheme, when the maximum to any one group was meant to be £50m.

The Treasury says it was not responsible for that decision, although correspondence reveals that Greensill was, again, able to make personal requests to Sunak’s department on that scheme.

All of which affirms the issue at the heart of the scandal: why was Cameron able to get one man and one company such access to the people who shaped Britain’s response to the pandemic – and why did Sunak agree to help him?

Cameron’s spokesman refused to respond on Sunday (AEST).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout