Crypto collapse is familiar tale of the big lie

Inventors from Thomas Edison to Steve Jobs on have followed a ‘fake it till you make it’ credo, but it only succeeds if investors suspend scepticism.

Until last week Sam Bankman-Fried, or “SBF” as he’s known, was a cargo-shorted, 30-year-old cryptocurrency billionaire who lived and worked in a $40m penthouse in the Bahamas in a sort of commune where he slept on beanbags with his friends, lovers and main colleagues.

He was hailed as the new JP Morgan. What could possibly go wrong?

Of course, everything. Late last week his companies collapsed, their value going from $32bn to zero. Investors – including a number of very serious venture capitalists – lost their stakes, while those who deposited their cryptocurrency in his FTX exchange company may very well lose some or all of their money.

In essence a theoretically separate part of Bankman-Fried’s operation – Alameda Research, itself worth far less than he was claiming – seems to have been allowed to make risky investments using FTX depositors’ money. When this fact became known, there was a run on deposits, the company’s value plummeted and a Trussian tragedy ensued.

My boomer’s knee jerked when I heard the news. Wasn’t this exactly what we would expect from the crypto world, with its incomprehensible blockchain and links to (shudder) the “dark web"? A world in which a crazy-haired, fidgety post-teen reveals that one of the secrets of his success is never having read a book and where he is praised by young writers for playing a video game called League of Legends while on business phone calls.

Yet, thinking it through, I realised that the lessons to be learnt here probably have very little to do with cryptocurrency. One of the reasons that SBF’s business flourished was that he offered a higher yield on deposits than anyone else. As the Wall Street Millennial website says, if you couldn’t see how he was managing such high yields, then “that just shows how you’re a boomer who doesn’t understand the magic of crypto”.

In other words, the desire to believe, the failure to be sceptical and the fear of missing out are the critical factors here. And they are not characteristics limited to the crypto world.

Tomorrow, another once-vaunted US new-tech prodigy, Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos, will be sentenced after having been found guilty of fraud. We reported on Monday that prosecutors are asking for a 15-year jail sentence.

Holmes was everything that SBF was but even more compelling. By the time she was 30 her Silicon Valley company was worth $9bn, based on the claim that it had created the technology to allow complex blood analysis to be done from a single finger-prick sample. No more “being stabbed with a big needle”, as Holmes hyperbolically put it.

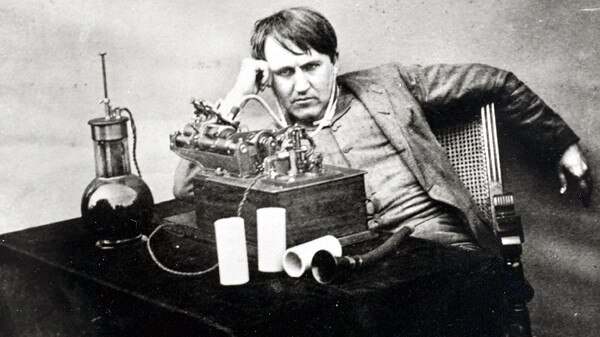

In America this would cut the high cost of blood tests, not least for the uninsured. The blood would be collected in a “nanotainer”, fed into a desktop machine called an “Edison”, after Holmes’s great hero, and quickly processed. Eventually you could get it done speedily and cheaply at your local drugstore. It would be a diagnostic revolution, and everybody (except the existing blood analysis companies) loves a diagnostic revolution.

Great personages such as Henry Kissinger and George Shultz adorned the Theranos board. Magazines carried Holmes’s winning picture on their front covers. Medical schools honoured her, politicians and celebrities were photographed alongside her. But secretly, in the sequestered patent-defending laboratory in the Theranos HQ, the people working on the project knew that the tech simply didn’t work.

A gap was opening up between what potential (and still vital) investors were being told and what was true. And to plug that gap, lies began to be told. Theranos would take blood samples as promised – though often using the big needle – process them conventionally using commercially available machinery made by companies such as Siemens, and then pass the results off as coming from Theranos’s own machines. It was a fraud.

Inside Theranos the conditions for a loudly blown whistle were developing. Outside, a few writers were wondering whether all was as it seemed. Holmes’s explanation of the science of her invention was described by a New Yorker writer as “comically vague”.

This description then piqued the interest of the Wall Street Journal writer John Carreyrou who, with assistance from the inside, uncovered what had been happening.

“Oy,” they all said, “how we were fooled! We believed in her! How could it have happened?” As they will now say of Bankman-Fried. But one clue to all this lies in the name of that Theranos machine. Thomas Alva Edison was a pioneer, but he was one who also lied.

In the late 1870s, knowing that there was a need and market for an incandescent light bulb, and believing he would eventually develop such a device, he simply rigged demonstrations of one, pulled in the investment money and – in the nick of time – managed to succeed. “Fake it ‘til you make it” became the motto of Silicon Valley. Edison made it in time. So did Steve Jobs at Apple. Holmes didn’t and was left with just the fake part. Bankman-Fried went the same way.

So what should we feel about this? Certainly we shouldn’t be too sorry for investors. As the tech entrepreneur Kathryn Parsons wrote in The Sunday Times last weekend: “Venture capital is about two things – making crazy big bets (venture) and making crazy big money (capital). The clue is in the name, folks.”

Especially in new and proprietary tech where no one really quite understands what anyone else is talking about. You flips your coin (or, rather, other people’s coins) and you takes your risk. Heads it’s a Jobs, tails it’s a Holmes.

Yet for ordinary folk it’s hard to take such a relaxed view. For us it can be our savings, or a false negative on a fraudulent blood test. We citizens can’t do our own due diligence, so we rely on regulators. For entrepreneurs and innovators who aren’t prepared to lie or fiddle their results or make claims they can’t back up, it could easily mean missing out on funding that goes to their less scrupulous rivals. We are too impressed by “front”.

Besides, boosterism as a form of leadership takes us to some bad places. Last December, to a fanfare of cracked trumpets, the then-trade secretary acclaimed her amazing trade deal with Australia. It was a deal, claimed Liz Truss, that “delivers for Britain and shows what we can achieve as a sovereign trading nation”, and more would surely follow.

Fake it ‘til you make it. And she made it. This week the man who was environment secretary at the time revealed that he had always thought it a bad deal. The UK, he said, “gave away far too much for far too little in return”.

Now he tells us.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout