Could AI kill the Brutalist’s Oscar chances?

A controversy over the use of voice-cloning software has dented the awards frontrunner. It’s not the first film to fall at the final hurdle.

Is it that time of awards season already? Time for the sudden and unexpected snowballing of negative media stories about an Oscar frontrunner that may, or may not, have a deleterious impact on its chances of winning one or more Academy Award?

Step forward this year’s Oscar frontrunner, The Brutalist.

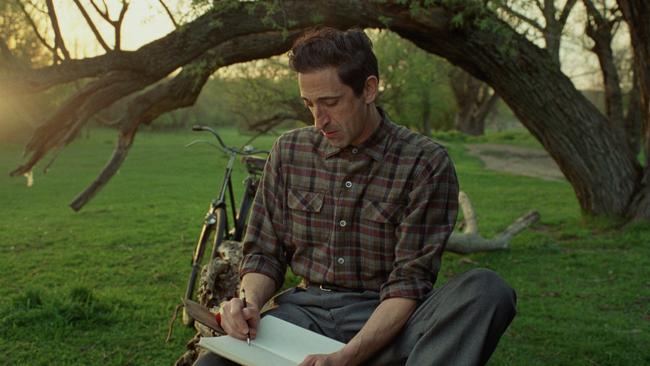

The film is a stunning historical epic about a Hungarian Holocaust survivor Laszlo Toth, played by Adrien Brody, who becomes a celebrated architect in postwar America.

Brody is hotly tipped to win the best actor Oscar, having bagged a Golden Globe, while the film’s equally lauded director, Brady Corbet, is considered a shoo-in for the directing and writing Oscars at the ceremony in March.

There’s just one snag. Recently an article, originally published by the tech website Red Shark News on January 11, became the focus of attention online because it revealed that the editor of The Brutalist used artificial intelligence software to correct some of the pronunciations of Brody and his co-star Felicity Jones during the few moments in the movie when they speak Hungarian.

In the interview, David Jancso said: “I am a native Hungarian speaker and I know that it is one of the most difficult languages to learn to pronounce … We also wanted to perfect it so that not even locals will spot any difference.

“If you’re coming from the Anglo-Saxon world certain sounds can be particularly hard to grasp. We first tried to ADR (automated dialogue replacement) these harder elements with the actors. Then we tried to ADR them completely with other actors but that just didn’t work. So we looked for other options of how to enhance it.”

The social media frenzy (typical post: “This is a disgrace!") became so intense that the detail-obsessed Corbet was forced to issue a clarifying statement where he explained that the AI software was used “specifically to refine certain vowels and letters for accuracy; no English language was changed”.

“Adrien and Felicity’s performances are completely their own,” Corbet added.

“The aim was to preserve the authenticity of Adrien and Felicity’s performances in another language, not to replace or alter them, and done with the utmost respect for the craft.”

That’s good to know, but it’s also hard not to feel that serious damage has been done to The Brutalist’s Oscar chances. And also to those of another awards frontrunner, Emilia Perez, after it emerged that the same AI cloning was used to blend the singing voice of the film’s star Karla Sofia Gascon with that of Camille, the French musician who co-wrote the musical’s score.

In Hollywood, AI has become a subject that instantly inflames passions and an industrial process from which most creatives want to be fully distanced. Heretic, for which Hugh Grant received a Golden Globe nomination for best actor, proudly trumpets its anti-AI stance in the end credits, with the words “No generative AI was used in the making of this film”.

It was the loathing and fear of AI that drove the crippling writers’ strike of 2023.

So the stain of AI on The Brutalist – however insignificant its actual application – is inevitably a blow to the Oscar hopes of Corbet, Brody et al. Meanwhile, Brody’s fellow frontrunners – including Daniel Craig for Queer, Timothee Chalamet for A Complete Unknown and Ralph Fiennes for Conclave – must be rubbing their hands right now, knowing that this media firestorm has elevated their Oscar prospects. That’s how fortunes change during awards seasons, although there is no suggestion that The Brutalist AI brouhaha was orchestrated.

What is known is that awards season has a recent and ignominious history of negative Oscar campaigning. It was Harvey Weinstein, naturally, who set the grubby standard in 1999 with his take-no-prisoners campaign for Shakespeare in Love. Back then he famously targeted the frontrunner Saving Private Ryan by planting the idea among journalists that Spielberg’s war movie was utterly boring after the first 20 minutes. It worked: Shakespeare in Love duly snapped up the best picture Oscar.

There were, of course, campaigns before Weinstein, but they tended to be accidental and haphazard. In 1960, the character actor Chill Wills paid for a promotional advertisement on behalf of his Oscar-nominated supporting turn in The Alamo. The ad invoked the real dead of the Alamo, and suggested that an Oscar win for Wills would dovetail with American manifest destiny and that, by extension, the other nominees were not quite as worthy. It backfired. His fellow nominee Peter Ustinov won the award for his performance in Spartacus.

Since Weinstein’s Shakespeare in Love win, however, negative campaigning has simply become an accepted part of the process, even as the execution of these campaigns has become increasingly sophisticated. With the advent of social media, the line between a negative campaign and seemingly organic online hysteria is almost impossible to see.

Bradley Cooper, for example, was the obvious frontrunner for last year’s best actor Oscar. His performance as Leonard Bernstein in Maestro was extraordinary, and arguably more complex and demanding than that of the award’s eventual winner, Cillian Murphy, for Oppenheimer. But Cooper’s decision to wear a prosthetic nose was deemed anti-Semitic by moral guardians online. The charge was nonsense, rubbished by Bernstein’s own children. But it hung around the movie like a crazed, Oscar-killing, one-word summation.

In January 2018, the much-adored Martin McDonagh drama Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri was heading for Oscar glory, for an easy best director and best picture win for McDonagh, or a best screenplay award at the very least. And then stories began to appear suggesting that the film was racist. Suddenly McDonagh was out and Guillermo del Toro (for the deeply naff The Shape of Water) was in.

Before the 2002 Oscars it was widely expected that Russell Crowe was going to achieve “the double” – a second best actor Oscar in a row, after his win for Gladiator the previous year.

This time he was going to triumph, as he had all season, for playing the Nobel-winning mathematician John Nash in A Beautiful Mind. But then online stories started to appear claiming that the real Nash was an anti-Semite and that the movie had whitewashed his character’s darker aspects.

Suddenly Crowe was out and the Oscar went to Denzel Washington for one of his most cartoonish performances, in Training Day.

The New York Times suggested that negative “whisper campaigns” were connected to “the rise of private Oscar strategists hired by the studios”.

What is assured is that the road to Oscars glory is dirty, slippery and filled with duplicity, and that a win on the night reflects a miracle, a work of unparalleled genius or, maybe, the actions of a marketing machine so sinister that it’ll whip up online frenzies about AI dialogue tweaks in an attempt to bring down a rightful champion.

The Times

The Brutalist is in cinemas.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout