Coronavirus: ‘Xi wolf’ envoys sink teeth into West

Beijing is encouraging its usually staid diplomats to attack those who question its response to the coronavirus outbreak.

In China’s vastly popular Wolf Warrior film blockbusters, a muscle-bound special forces commando vanquishes “bad guys” in the form of American mercenaries across Africa and Asia.

The mix of jingoism and all-action frenzy showcasing the heroics of an elite unit of the People’s Liberation Army was box-office gold in China.

Now a very different breed of Chinese fighters is going into battle to promote the motherland’s interests in global clashes over the coronavirus. They are China’s “wolf warrior diplomats”, named after the films.

Traditionally, Chinese envoys have cut colourless figures, sticking to staid, carefully regimented speeches while shunning the limelight. But no longer.

Those protocols have been jettisoned on orders from Beijing. Transformed from taciturn to truculent, they are lashing out against criticism of China, portraying their boss, President Xi Jinping, as the pandemic saviour and delivering fiery attacks on their host nations.

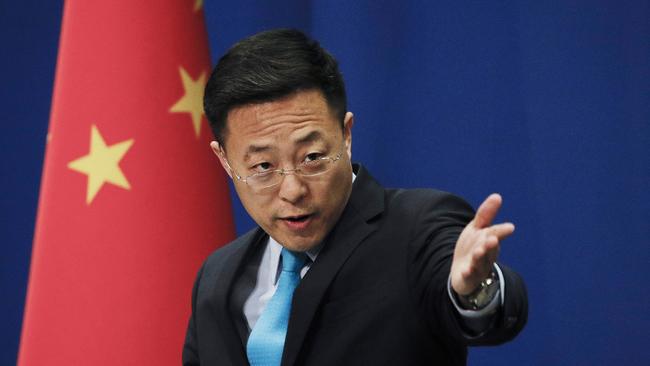

The master practitioner is Zhao Lijian, the 47-year-old foreign ministry spokesman, viewed as a role model by a new generation of nationalist cadres.

He pushed the Chinese internet conspiracy theory that the virus was brought to Wuhan by American soldiers participating in the World Military Games. And his influence was seen in last week’s unsigned foreign ministry tweet calling on the US to address alleged fears in former Soviet republics about the safety of its “biological labs” — another popular target on nationalist social media.

Zhao first came to international prominence as deputy ambassador in Pakistan with his fierce Twitter defences of controversial Chinese investment projects. As his social media following soared, he ranged broadly, responding to global condemnation of the mass internment of China’s Uighur Muslims with an unbridled assault on American racism.

Susan Rice, the former US ambassador to the UN, who is African-American, denounced Zhao as a “racist disgrace” who should be dismissed. When he was recalled to Beijing soon afterwards, some thought he had paid the price for his outspokenness. Instead, he was promoted to China’s voice and face for the world.

Zhao is believed to have played a key role in drawing up the new digital attack strategy, which some analysts believe was in part inspired by Donald Trump’s use of Twitter.

It was relayed to seasoned ambassadors in a pep talk at a closed-door meeting in Beijing late last year when Foreign Minister Wang Yi told the envoys to display stronger “fighting spirit” to counter international challenges. On Beijing’s mind then was the Sino-US trade war and the Hong Kong protests. But the frontline soon became the coronavirus.

Chinese people “are no longer satisfied with a flaccid diplomatic tone”, Global Times, the tub-thumping party newspaper, declared last month. “The days when China can be put in a submissive position are long gone.”

The jettisoning of the former leader Deng Xiaoping’s dictum for diplomacy — “hide your strength, bide your time” — could not be clearer.

Dozens of ambassadors have joined Twitter and Facebook, social media platforms banned in their own country, as they unleash decidedly undiplomatic firestorms from Caracas to Canberra.

Australia was the setting for the latest offensive after Scott Morrison called for an independent investigation by foreign inspectors into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cheng Jingye, the ambassador, raised the spectre of a boycott of Australia and its products by Chinese tourists, students and consumers, while his officials denounced Australian politicians as parroting orders from Washington.

Foreign Minister Marise Payne denounced this as attempted “economic coercion”. As the row spiralled, the Global Times editor, Hi Xijing, chimed in, likening Australia to “chewed gum on the bottom of a shoe”.

The playbook for Beijing’s representatives is to argue that China bought the world time while fighting the virus and then magnanimously dispatched medical aid and doctors to help others — while not of course mentioning that much of the “aid” came with a large price tag and is too shoddy to use.

They fire off angry missives to denounce any reference to the “Chinese” or “Wuhan” virus, although the latter term was for several weeks preferred by the state media as officials portrayed the outbreak as a localised affair for the ground-zero city.

Any talk of seeking compensation or establishing outside investigations — both are being widely discussed in foreign capitals, no longer just the preserve of China hawks in the Trump administration — are met with ferocious denunciation.

If Beijing’s strategy was to win friends and influence people overseas, or pursue the traditional goal for diplomacy of solving differences and disputes, then the strident take-no-prisoners approach would be manifestly failing.

But the primary purpose of Beijing’s foreign policy is to play to a domestic audience and protect the Chinese Communist Party and its leadership, said Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

“Wolf warrior diplomacy came into existence as senior Chinese diplomats went into overdrive to ingratiate themselves with Xi by appearing like his good footsoldiers taking on elements outside China that are ‘hostile’ to China — for which they really mean Xi’s leadership,” said Tsang.

“Pushing the arguments that China under the leadership of the CCP and Xi is the saviour of the world over COVID-19, that they enabled China to do so much better than western democracies, and that the virus probably originated outside China, are important in getting the general public in China to feel patriotic and proud and rally around the party and the leadership of Xi.”

Zhou and the Global Times portray the new approach as standing up to the West. But the targets for the rancorous wranglings of “wolf warrior” diplomacy are global.

In Paris, the Chinese ambassador was called in for a demarche after his embassy responded to criticism of China’s handling of the coronavirus with a Facebook statement accusing French care home workers of deserting their posts and “letting residents die from starvation and disease”.

The French were furious. And that contretemps spilled into a high-profile showdown with the EU over allegations that Chinese missions were spreading disinformation and fake news. Brussels has denied that it caved in to veiled Chinese threats to reduce investments when it cut references to the care home claims from an EU report.

In a move that will further raise Beijing’s hackles, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen on Friday backed calls by a growing band of European politicians for an investigation into the origins of the coronavirus.

Embassies have also targeted media outlets in an attempt to muzzle unfavourable coverage. The mission in Stockholm berated journalists for “waging ideological attacks” that would only “sabotage” Sweden.

Relations were already at a low ebb there after the ambassador noted darkly that “we treat our friends with fine wine, but for our enemies we use shotguns” following a free speech award to Gui Minhai, a Swedish citizen and former Hong Kong bookseller jailed on the mainland.

The Sunday Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout