Coronavirus: Second wave pours cold water on German and Swedish strategies

Germany considers tougher measures while Sweden backtracks, implementing harder restrictions after relying on an appeal to folkvett — good manners and respect for fellow citizens.

When COVID-19 struck Germany in the northern spring, Chancellor Angela Merkel won plaudits for the calm determination with which she dealt with the pandemic.

Across the Baltic Sea, Sweden’s way of life was barely interrupted as the country became a beacon for libertarians across the world who opposed national lockdowns.

The practical north Europeans seemed to be proceeding confidently, while Britain, France, Italy and Spain floundered in the face of an ever-mounting death toll. Now, however, their magic touch seems less convincing.

As Merkel grapples with a second and more powerful wave of the virus — with new cases hitting a daily record of 23,648 on Friday — she is struggling to win the backing of Germany’s regional leaders for tougher curbs.

Those who argue that even the “lockdown lite” in force since the start of the month goes too far are protesting on the streets, claiming infringement of their civil liberties.

While Germany ponders tougher measures, they are already being implemented in Sweden, one of the few countries in the developed world not to impose a formal lockdown during the first wave. Sweden relied instead on an appeal to folkvett — good manners and respect for fellow citizens.

From Friday night, bars and restaurants in Sweden were banned from serving alcohol after 10pm. For the first time in 129 years, Skansen — the world’s oldest open-air museum and a vital part of Stockholm’s cultural life — closed to visitors.

With new reported cases soaring recently to as many as 6700 a day — in a population of just over 10 million — the Swedish government is beginning to distance itself from the former light-touch approach of the health authorities.

“It is November, one of the year’s darkest months, and this darkness will only become worse going forward,” Prime Minister Stefan Lofven said at an unremittingly grim news conference last week.

“Unfortunately it looks like we are going towards darker times when it comes to the spread of the virus. All the indicators are pointing the wrong way.”

Andrew Ewing, professor of chemistry and molecular biology at Gothenburg University and a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, who has been heavily critical of the state’s response, said: “Obviously these (recommendations) should have come earlier. But they do not go far enough. They are nowhere near as tight as in the UK.”

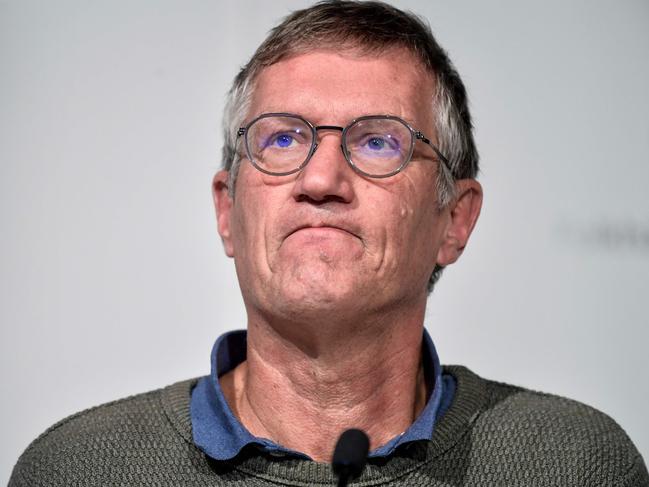

Last week the academy issued a statement strongly recommending use of masks in busy indoor spaces — in apparent defiance of the chief epidemiologist, Anders Tegnell, who led the state response in the first wave and has argued there is not enough evidence masks work outside a clinical environment to necessitate their widespread use.

“There are no requirements for masks here and hardly anyone wears them — sometimes not even in the hospitals,” said Ewing. “It comes down to one word: prestige. The guy who is running the show said in the spring that masks don’t work and he just refuses to back down.”

Germany’s decentralised political and health system is widely credited with having helped it keep the virus under far better control than most of its European neighbours after the first case was detected in late January at a car parts supplier in Bavaria.

The German death toll, set to pass 14,000 over the weekend, is also still only about a quarter of that in Britain, France and Italy despite its much larger population.

Yet decentralisation can have its drawbacks, as Merkel found last week when she tried and failed to win backing for a unified approach to fighting the virus from the leaders of the 16 Lander (states), whose attitudes are shaped by the varying degree to which their regions have been hit by the pandemic.

This week she is due to try to convince them at another meeting, when prominence will be given to measures to curb infection among teenagers and young adults who “contribute significantly to the spread of the infection”, according to Helge Braun, Merkel’s chief of staff.

Resistance is not just restricted to some regional politicians: as parliament met on Wednesday to vote on a law to provide a more solid legal basis for the existing COVID-related restrictions, thousands of people demonstrated in Berlin before their anti-lockdown protest was broken up by police with water cannon.

The populist right-wing Alternative for Germany party went as far as to compare the new law with the Enabling Act of 1933 that paved the way for Hitler’s dictatorship, and smuggled some of the demonstrators into parliament, where they proceeded to harass MPs.

The Sunday Times

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout