Coronavirus: Heinsberg, ‘Germany’s Wuhan’ could hold vital virus key

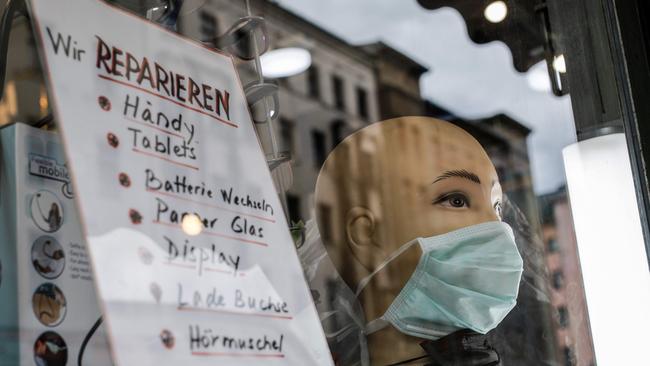

Initially ostracised as ‘corona spreaders’, all eyes are now on residents of a German city as scientists begin key research.

For a few weeks the people of Heinsberg, a quiet corner of Germany jammed up against the Dutch border, were treated like the outcasts of northern Europe.

Retail chains refused to deliver to their homes. The region’s handymen and technicians were insulted and spat upon outside the district.

A short drive away in the Netherlands, cars with Heinsberg number plates were jeered as “corona spreaders” or forced to park in segregated spaces. Some residents say that they were prevented from getting out of their vehicles.

Now, though, the area described as “Germany’s Wuhan” — the ground zero of the country’s first serious COVID-199 outbreak — is drawing a different kind of attention.

Scientists believe it holds the answers to decisive but unresolved questions that could make the difference between an indefinite future under lockdown and a gradual return to normal life.

A team of 40 researchers will spend the coming days in the region trying to work out how the virus truly spreads, how many people are infected without knowing, and which measures have helped to slow the disease.

It is the first study of its kind and the ramifications are likely to carry far beyond the German borders. The idea, as Armin Laschet, chief minister of the surrounding state of North Rhine-Westphalia puts it, is to find out “which of the steps we have taken and our deep intrusions into the lives of our citizens remain scientifically meaningful, and which aren’t”.

Heinsberg is something like a portal into the near future. The full force of coronavirus hit the district earlier and harder than any other part of Germany.

On February 15, while the disease still seemed like a distant threat largely confined to the Far East, 300 people gathered for the annual Langbroker Dicke Flaa carnival in the villages of Langbroich and Harzelt.

Under grey skies, a procession of tractors towed a mock-Roman palace and a gaudy circus tent through the streets as men in clown suits and mickey mouse costumes swigged from bottles of beer in their wake.

It was a silent catastrophe. Ten days later, a couple in their mid-forties who had attended the carnival were admitted to hospital with mysterious respiratory symptoms even though they had no underlying health conditions.

“I received the news on the afternoon of Shrove Tuesday [February 25],” Stephan Pusch, the leader of Heinsberg council, said. “Within 40 minutes we set up the crisis management team.”

The speed of the response was breathtaking. Over the next two days the council quarantined 1000 people in their homes, shut every school and nursery and temporarily closed its buildings to the public.

Yet the numbers became worse. By the end of the week, 60 infections had been traced back to the carnival. A week later it was 220. The first victim, a 78-year-old man who lived near Langbroich, died three days after that.

As of Wednesday evening, Heinsberg had 1302 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 37 deaths in a population of 250,000, with an infection rate five times higher than the German average.

As if that were not bad enough, Heinsbergers were shunned by their neighbours. After an appeal to the German military for protective equipment went unanswered, the district sent a letter directly to Beijing through the Chinese consulate in Dusseldorf.

People ‘took fright’ at residents

“People in other west German cities took fright as soon as they saw a car with the ‘HS’ number plate. Some fitters [from Heinsberg] were turned away at the door by their clients purely because of their number plates.”

Now, however, more or less the entirety of Europe is stricken. Heinsberg is no longer a colony of outcasts so much as the vanguard of Germany’s efforts to keep a lid on COVID-19. This week and next researchers led by Hendrick Streeck, the director of the institute for virology at Bonn University, will test a representative sample of 1,000 Heinsbergers for the virus.

The results, the first of which could be released in days, will be crucial in shaping the response to the pandemic. If, for example, it should turn out that a large proportion of the sample are carrying the virus with no symptoms, Europe may have a far worse problem on its hands than it thinks, in the shape of a hidden reservoir of disease.

Cluster study

If, on the other hand, the council’s drastic measures turn out to have done the job, the “COVID-19 cluster study” could strengthen the case for lifting some restrictions within weeks.

There are signs that the white heat of the epidemic is beginning to die down. Each day brings fewer new cases. It is possible that the mass quarantines and the abrupt shutdown may have saved dozens if not hundreds of lives.

Heinsberg also serves as a textbook example of how to keep up morale when people are trapped in their own homes and scorned by the world outside. Mr Pusch’s daily video messages to his constituents have been watched by as many as 60,000 people, nearly a quarter of the district’s population.

A simple slogan devised by Frank Reifenrath, the boss of a local financial consultancy – #hsbestrong – is now also proudly displayed on thousands of social media profiles. He said: “We could become a blueprint for economic downfall, but we could just as well become a blueprint for the revival.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout