CJ Sansom’s Tudor sleuth Matthew Shardlake intrigued millions

CJ Sansom overcame a troubled childhood to produce the best-selling Shardlake novels.

Obituary

CJ Sansom Historical crime novelist

Born Edinburgh, September 9, 1952; died Brighton, England, April 27, aged 71.

CJ Sansom was in his late 40s when an inheritance enabled him to give up his job as a solicitor for a year to write fiction and “see what happened”. His twin obsessions were popular crime novels and the Tudor dynasty, and in combining the two he arguably invented a literary genre.

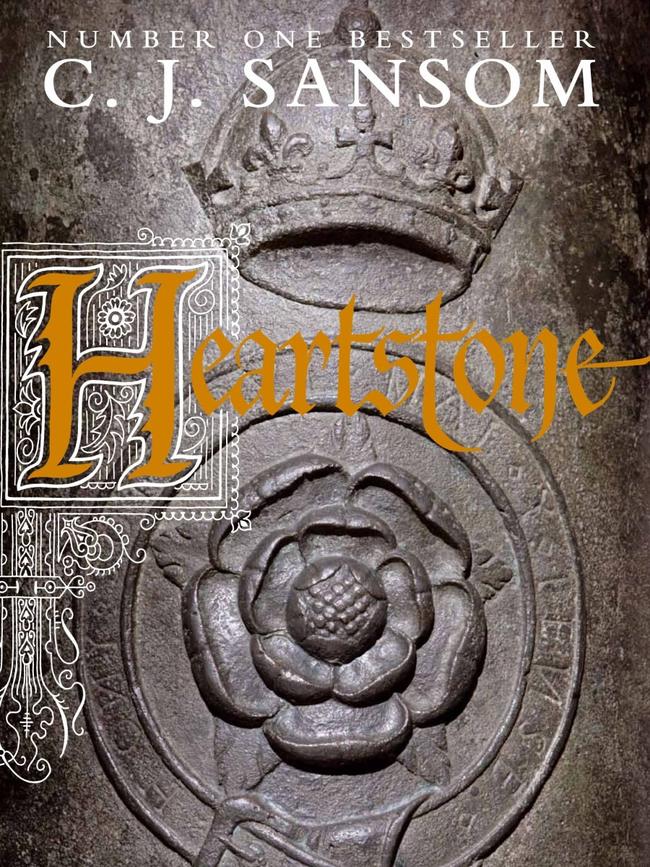

By the end of that year he had finished a draft of what would become his first novel, Dissolution. It was an instant bestseller on publication in 2003. Sansom would go on to sell nearly four million copies in the seven-book series featuring hunchbacked lawyer Matthew Shardlake, who solves murder mysteries related to the religious psychodrama roiling Tudor England from 1537 to 1549, amid endless political intrigue in the court of Henry VIII and scatological odours on the streets of London, York, Portsmouth and Norwich.

The likeable but complicated lawyer sleuth, who is socially awkward and unlucky in love, was something of an alter ego of the author. Sansom was, by his own admission, a loner, psychologically damaged by the relentless bullying he endured during his school years but with an endearingly boyish enthusiasm that came to the fore when he talked about his work.

In a Sunday Times profile in 2018, Rosie Kinchen wrote of approaching his book-lined townhouse: “Stiff and severe, he stands at the window watching me approach his Brighton home but does not open the door until I have rung the doorbell as expected.” Once inside she noted six coasters of Henry VIII’s wives neatly lined up on a coffee table.

Dissolution introduces Shardlake working for Henry VIII’s chief minister Thomas Cromwell, who dispatches him to Sussex to investigate the murder of one of Cromwell’s commissioners during the dissolution of the monasteries in 1537. The result was far more than a page-turning whodunit.

“We watch him attempt to reconcile an intellectual sympathy for Cromwell’s reformation with revulsion at the acts undertaken in its name,” wrote one reviewer. “Shardlake is a thoughtful, nuanced presence in a sea of religious zealotry, ignorance and superstition; of his time, but not blinkered by it.”

Dark Fire (2004) further explored Cromwell, less sympathetically than Hilary Mantel would do in Wolf Hall.

“Cromwell as a character is ripe for interpretation,” Sansom said. “He’s been controversial ever since he had his head cut off: some think he was the blackest of villains; others that he was a great, positive reformer. I’m somewhere in the middle, but I do believe he had a dark side; much darker and more brutal than Mantel’s portrayal.”

The series provides a decent history lesson. Indeed Sansom was himself a graduate of the subject and a rigorous researcher. Historical inaccuracies for the purposes of the plot and narrative would be owned up to in the historical note, which was always comprehensive.

And if Shardlake was an essentially modern character, replete with cautionary analogies to the modern world, Sansom partially admitted the charge. “It’s difficult, perhaps impossible, to write a character well in the past who is not a projection back of modern sensibilities,” he said in 2010. “My defence would be that the 16th century was the time when rational, sceptical inquiry was beginning. I’m not saying a man like Shardlake did exist then, but he could have, where even 20 years earlier he couldn’t. That’s enough for me.”

Christopher John Sansom was born in Edinburgh in 1952 to Trevor, a naval engineer, and his wife Ann. Growing up in a traditional Presbyterian household that was “Conservative with a small c and a capital C”, he described himself as a “noisy and uncontrollable” infant and “a trial and a puzzle to my parents”.

George Watson’s College in Edinburgh was a living hell. Struggling with undiagnosed ADHD, Sansom could not concentrate. Unusually tall, skinny, awkward and shy, he was a natural target for bullies. Abuse was never violent or sexual but he felt “permanently scarred” by memories of hiding in a lavatory to escape jeering boys. “The teachers blamed this on me and sometimes collaborated in it.” He escaped into books.

“By the time I was 14, I was, I now realise, becoming seriously mentally ill: completely isolated, hardly aware of what was being said in the classroom, consumed with rage, plagued by migraines and tormented by thoughts of suicide and burning down the school.”

Aged 15, he nearly died after taking an overdose of his mother’s sleeping pills and was committed to a mental hospital for a year.

“For the first time in my life, I was not treated as a pariah, and I owe more than I can say to the devotedly caring staff. They saved my life. My mind came to life and I found interests in literature, history and politics.”

Sansom completed his secondary education at a different college, studied history at Birmingham University and gained a PhD. He trained as a solicitor, mainly working on legal aid cases so he could “act on behalf of the underdog”.

Law provided structure and rules for his own confused existence, and it made sense for Shardlake to work in the profession.

“(Legal practice) existed then and now, so it provides a point of contact for readers. And it offers a way into any number of mysteries, and puts Shardlake in the way of an endless variety of characters.”

Sansom’s novels made him rich, but living alone he continued to struggle with intermittent depression. He was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2012 and illness prevented him from publishing an eighth planned Shardlake novel, set during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, “someone I actually like”.

Dissolution and Revelation were serialised by BBC Radio 4, but he did not live to see the Disney+ series based on his novels, starring Arthur Hughes as Shardlake and Sean Bean as Cromwell, which has just begun streaming.

PD James was a great friend and mentor. On being given a copy of Sansom’s hefty novel Lamentation one month before her death at the age of 94 in 2014, the distinguished crime novelist said: “This will see me out.”

The Times

Beyond Blue 1300 224636; Lifeline 131114