China’s ‘wolf-warrior’ diplomats raise hackles around the world

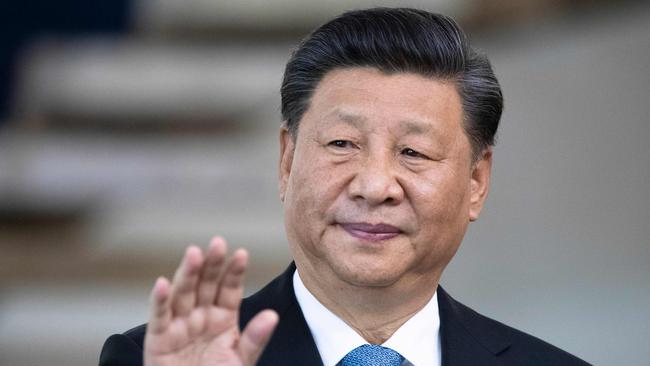

Xi Jinping’s drive to secure China’s place at the top table has been embraced by an aggressive new breed of envoy.

A “small-time thug”, an “ideological troll” and a “crazed hyena”. The language may be colourful but not unusually abusive by the standard of social media discourse. Delivered by the Chinese ambassador to France, however, and aimed at a critical academic, it was sufficiently undiplomatic to prompt an official summons — which the ambassador, Lu Shaye, simply ignored.

A similar incident occurred in Alaska, at the Biden administration’s first meeting with Chinese officials, when a four-minute photo shoot descended into an hour of barb-trading after China responded to concerns about human rights abuses in Xinjiang with accusations that African-Americans were being “slaughtered” in the streets.

In Prague, the Chinese ambassador demanded that the city’s mayor eject a representative of Taiwan from his New Year’s Eve party; an incident that culminated in the cancellation of a tour of China by the Prague Philharmonic orchestra, and the end of the twinning of Beijing and Prague.

Such public clashes are a far cry from the rarefied style of old-school diplomacy, adhering rigidly to protocols governing state-to-state interactions such as obeying an official summons. China’s diplomats were once among the most buttoned-up of all, sticking so closely to their stilted official scripts that journalists played word bingo to pass the time during interminable official briefings.

All that has changed in barely five years as President Xi Jinping sets about transforming his country’s place in the world, aided by the “wolf warrior” diplomats representing the nation abroad.

The old model of Chinese diplomacy was represented by Deng Xiaoping’s extortions to “hide our light and bide our time”. Instead of merely defending their country against foreign criticism, the wolf warriors now compete for proactive attacks on any nation, official or private citizen who seem to suggest that western systems might be superior to China’s authoritarian rule.

The term “wolf warrior” is taken from a 2017 Chinese nationalistic action film franchise featuring Rambo-like special forces fighters who do battle against a drug lord protected by American mercenaries. While China has long trained its diplomats to be “plainclothes soldiers” the phenomenon was born of Xi’s specific exhortations to “dare to fight” on China’s behalf.

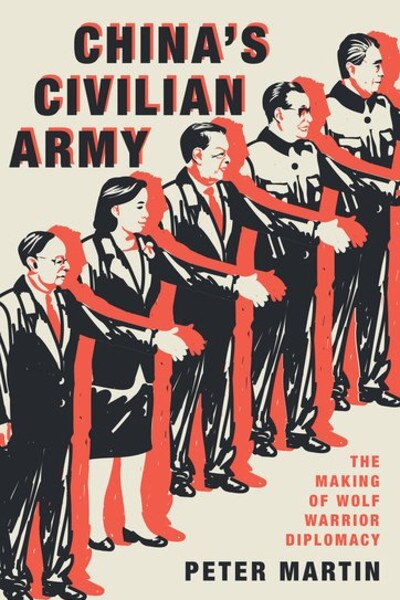

Peter Martin, author of China’s Civilian Army: The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy, argues that the change is driven as much by the personality cult of Xi than by any evidence of its effectiveness. “The impulse for Chinese diplomats to follow Xi’s lead is rooted in fear as well as ambition,” he writes. “The easiest way for diplomats to work towards Xi’s wishes is to assert Chinese interests forcefully on the world stage.”

Perhaps no one embodies the new spirit as much as Zhao Lijian, the foreign ministry’s combative spokesman and one of the pioneers of digital wolf-warrior diplomacy. He was one of the first Chinese diplomats to open an account on Twitter, which is blocked within China. He returned to Beijing after a very public spat with his Pakistani hosts and suspicions that his career was over, but then re-emerged as the ministry’s public voice and began urging other diplomats to establish a presence on Twitter. To date, 189 senior Chinese diplomats have active accounts, posting hundreds of tweets each every month, an activity level matched only by their Russian counterparts.

Zhao used Twitter to launch some of his wilder accusations at the US, including the assertion that its military brought the coronavirus to China while attending a sporting contest. At an in-person briefing in Beijing he warned the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing network “to be careful not to be poked and left blind” after criticism of the crackdown in Hong Kong.

Zhao’s rise accompanied an increasing takeover of the foreign ministry by those who have risen through the ranks of the Communist Party rather than traditional career diplomats, often viewed with suspicion by loyal party cadres because of their time spent abroad associating with foreigners.

Charles Parton, a former British diplomat in China, notes that far from being reined in, the most vocal of the wolf warriors have been lauded and promoted. “Nobody who has done this has suffered for it,” he said, despite several instances in which their interventions have clearly harmed relations with their host countries.

He singled out Lu Shaye, the combative Chinese ambassador to France, as one of the most active bomb-throwers on the diplomatic circuit. In 2016 Shaye called on fellow diplomats to do battle with the West to force acceptance of “China standing at the top of the world”. After being sent as ambassador to Canada in 2018 he accused the government there of “Western egotism and white supremacy” after police arrested a Huawei executive wanted for extradition to America.

Moving to Paris last year, Lu wasted little time in going into battle against the French, posting essays accusing French care homes of leaving residents to die, and personally attacking a private researcher who wrote in support of relations with Taiwan. He insists he is projecting Chinese confidence not aggression. “It’s a form of proactive diplomacy,” he told the French newspaper L’Opinion.

His position was echoed by the Global Times, the Communist Party’s English-language organ, which suggested that China’s new assertive face was appropriate to its changed global position. “What’s behind China’s perceived “wolf warrior’ style diplomacy is the changing strengths of China and the West,” an editorial noted. “The days when China can be put in a submissive position are long gone. China’s rising status in the world requires it to safeguard its national interests in an unequivocal way.”

Yet geopolitical fears also fuel the aggressive intersections. Officials in Bangladesh, which has sought to stay out of the regional geopolitics battle, were stunned last week when the Chinese ambassador in Dhaka started threatening the government with dire consequences if it joined the Quad, a loose alliance between India, Australia, Japan and the US. Bangladesh had never as much as even indicated it was trying to do so.

There is little evidence that the approach wins hearts or minds overseas. An investigation by the Oxford Internet Institute found that China’s social media rise has been powered by armies of fake accounts falsely amplifying its message. More than half the retweets received by the former ambassador in London, Liu Xiaoming, last year were traced to Twitter accounts that were later suspended.

Liu, now China’s special representative on Korean peninsula affairs, has cast himself as one of his country’s foremost digital warriors, tweeting in February: “There are so-called wolf warriors because there are ‘wolves’ in the world and you need warriors to fight them.”

But Chinese diplomats such as Liu may struggle in more conventional settings. He was left stuttering helplessly when confronted live on The Andrew Marr Show on the BBC with video showing blindfolded, cuffed Uighur detainees being taken to “re-education” camps.

Some old-school Chinese representatives believe the approach is overly aggressive and costs the country goodwill abroad. In an interview shared widely on social media, Yuan Nansheng, a retired ambassador, argued that Chinese diplomacy “should get ‘stronger’ and not simply ‘harder’”.

To Parton, the issue of whether the new posture yields diplomatic results is secondary to the face that Xi wants China to put on for the world. “Everything comes secondary to how it plays on the domestic front,” he said. “When policy is about China rising and the West declining, the rhetoric is being ramped up.”

Indeed, China nationalists celebrated the tough words in Alaska while the cameras were there; verbal acrobatics that might actually spare Beijing from having to take strong concrete action. After the cameras left, the two sides reported “candid, constructive and beneficial conversation, even according to China’s top wolf warrior, Yang Jiechi. “But of course there are still differences,” he quickly added.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout