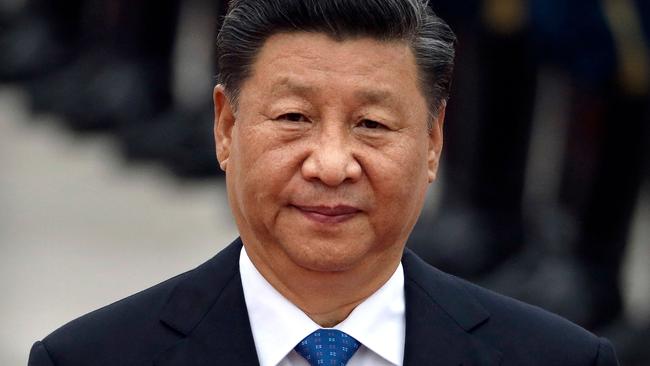

China’s pension crisis threatens Xi’s regime

Are the Chinese dying out? Beijing fears how citizens will react if they’re told to work longer due to a falling birth rate.

Are the Chinese dying out? That’s the headline Xi Jinping doesn’t want to read in a year which is supposed to trumpet the achievements of a century of home-grown communism. Little wonder then that the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) in Beijing’s Xicheng district is in intellectual lockdown as the number-crunchers massage the figures from the 2020 census. The figures were in before the end of December, were due to be released in April but are still being withheld at official behest.

The NBS, with its chattering fax machines, has become the National Bureau of Secrets. The true figures for the unemployed and under-employed?

The supreme authorities don’t want to know. Not when a nationwide propaganda film season is being prepared (watch out for the 1963 Mao Zedong-era epic Red Sun), when Nanjing is planning mass weddings and when the Chinese economy is beginning to speed up.

And they certainly don’t want to hear that the nominal Chinese population of 1.4 billion may have slipped closer to India’s 1.38 billion, maybe even lower. Size matters to Xi in an anniversary year when he is trying to promote China’s advantages over the United States and present the country’s autocratic model as the way of the future. Yet there is no wishing away the facts and the social engineering blunders of the past. The low fertility rates common to much of the world last year have been compounded by the disastrous long-term effects of the one-child policy that lasted from 1979 to 2016.

It is good news, on the face of it, that life expectancy has been improving apace. In the 1950s the average citizen in China was expected to live until their early forties. By 1990 that had improved, thanks to better healthcare and nutrition, to 69, which compared to about 75 in the US and UK and 78 in Japan. Now, according to World Bank data, the Chinese can reckon on living on average to almost 77, not much below Britain and the US. Japan remains an outlier, with men living until 81 and women 87.

Nevertheless this masks a series of problems. Retirement ages in China were pinned to shorter life spans. Blue-collar female workers can still expect to retire at 50, white-collar women at 55, and most men at about 60. At one end of the demographic spectrum fewer babies are being born and young adults are entering the world of work later; at the other end workers are rushing to take their state pension at what most western societies would regard as middle age. It’s a top-heavy society. By 2025, about one fifth of the population will be over the age of 60. By 2050, at the current rate, there will be more than three times as many older citizens as children.

What price, then, Xi’s claims that his nation is the rising global leader, overtaking the US as a powerhouse and setter of rules? China’s huge population of consumers and producers defines its power to make or break global markets. A big pool of young men supplies an army of more than two million. There’s no such thing as an army of old men. And though China is in a rush to robotise its factories – stealing western robot tech was an espionage priority for decades – it doesn’t do so very effectively.

It is the politically explosive question of raising the pension age that bothers Xi. Not the muzzling of Hong Kong, not even the mass abuse of the Uighurs: it is the angry pensioner that could speed his downfall. Democratic societies with low birth rates, caused not so much by libido-sapping lockdowns as an unwillingness to expand families in uncertain times, have ways of dealing with this. Sometimes, as in France, raising the pension age leads to strike action and protests on the streets. Often the answer is sought in more liberal immigration rules. Xi won’t tread that path.

Russia 2018 is what rattles Xi the most. The Putin regime deliberately introduced pension reforms on the opening day of the World Cup, which Russia was hosting. All demonstrations had been banned until the end of the tournament in order to give an orderly impression. Soon after the final whistle, thousands started to protest every weekend. The dissident Alexei Navalny got involved and helped spread the demonstrations to 60 cities. In September’s elections Putin’s United Russia party scored its worst ever result. His popularity dropped from the high 70s to 48 per cent.

Russians are still sour about it. And the Chinese, fearing what is around the corner, are already tense. They see pension reform as an assault not only on their quality of life but on the family itself. Grandparents, still hale and hearty, are an indispensable part of childcare. If they have to work until the bitter end then something changes in the balance between the generations.

That’s an intrusion too far by the party. Xi, though forced to modernise, is worried that he will burn through his capital as self-proclaimed father of the nation.

There is an alternative story to be told about the way that communism established itself in China, one that doesn’t dwell on heroic leadership. It stretches from the millions of people lost in the famines of the 1950s, the grisly enforced sterilisations of the one-child policy that saw girls aborted and the black market sale of kids, to the effective dispatch to the knacker’s yard of the over-60s. That is a shadowy story which Xi is in no hurry to tell.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout