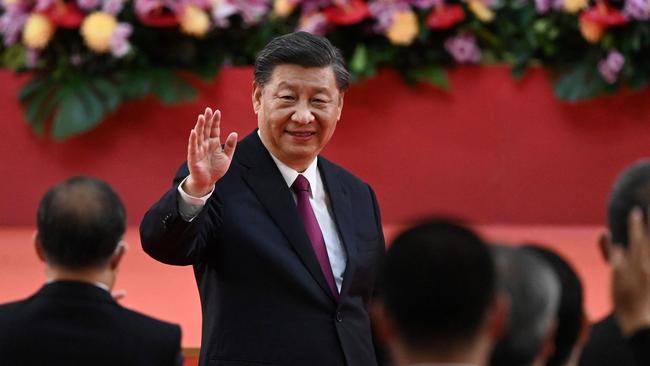

Chairman Xi Jinping may not have it all his own way

The 20th congress of the Chinese Communist Party is due in October and so sure of the result are the organisers that Beijing’s diplomats have been sounding out a potential group visit in November by European leaders from Germany, France, Italy (now complicated by the collapse of the government in Rome) and Spain. No mention of Britain. The big strategic idea: it’s time for a Chinese leader with enhanced powers to build bridges with friends and amplify Beijing’s influence. At about the same time, the Chinese may be calculating, Joe Biden will be taking a battering in the midterm elections. It could be Xi’s “Now who’s boss?” moment.

Or not. There’s plenty going wrong in China. The Covid lockdown in Shanghai has binned all growth assumptions. Last year China notched up an 8.1 per cent rise in GDP and the target for this year was 5.5 per cent. However, long Covid is not just a medical phenomenon. Second-quarter growth was barely 0.4 per cent year on year. Much of the public standing of the leadership is based on the unwritten social contract that you sacrifice certain individual liberties in return for prosperity and security.

That’s dropped out of the window. A couple of weeks ago hundreds of protesters tried to storm a branch of the People’s Bank of China to recover $6 billion worth of deposits they said had been stolen from them. Plainclothes police fought them off. Cyberunits manipulated the personal health apps of more than 1,000 aggrieved depositors to suggest they were at high risk of Covid-19 and were therefore liable to instant arrest if they were caught in a protest.

There are pockets of dissent everywhere. The liquidity crisis sweeping through the Chinese property sector is prompting apartment buyers to stop paying mortgages on uncompleted building work. Beijing has ordered a bailout fund and local government has been told to disburse it, but protesters are contacting fellow complainants across the country.

Most measurements of Xi’s performance find him wanting. China was supposed to be the infrastructure king. In fact it has only 106km of railway per one million citizens. Britain has 263km per million people. The big boast, that the Communist Party has dragged the population out of poverty and illiteracy, has lost its shine in the Xi era. According to the Chinese census, the proportion of 25 to 64-year-olds with a high school education is 36.6 per cent. That is below Mexico, Turkey and South Africa and well under the G20 average.

It is not difficult to spot the gap between Xi the leader, pumped up by a relentless cult of personality, and Xi the man who presides over a country scraping the bottom of some G20 league tables. The charitable explanation: the regime has been censoring its own people for so long it doesn’t know what’s going on in the country.

That rather lame excuse stopped working during the serial lockdowns when a combination of inferior vaccines and rigid quarantines failed to work. “Shanghai: zero movement, zero GDP,” wrote a senior banker on Weibo, China’s version of Twitter. The banker, with three million followers, immediately had his account suspended. Tech entrepreneurs have found themselves quickly sidelined if they voice even implied political criticism. Xi recognises the need for tech innovation, but may fear the spontaneity it can inspire in society. Local discontent has always bubbled under the surface, notably clean air campaigners in besmogged cities, and is usually smothered or ignored. Before a big party congress though, the moaning gets taken up by loose coalitions of activists jostling for position.

The late (but long lived) reformer Deng Xiaoping set out four guiding principles of communist leadership: no excessive concentration of power; a clear separation of the party from the technocratic functions of government; the promotion of the young to prevent a succession crisis; and no fawning praise for the leader. Nowadays anyone who published those principles could expect a knock on the door because each point could be read as a critique of Xi.

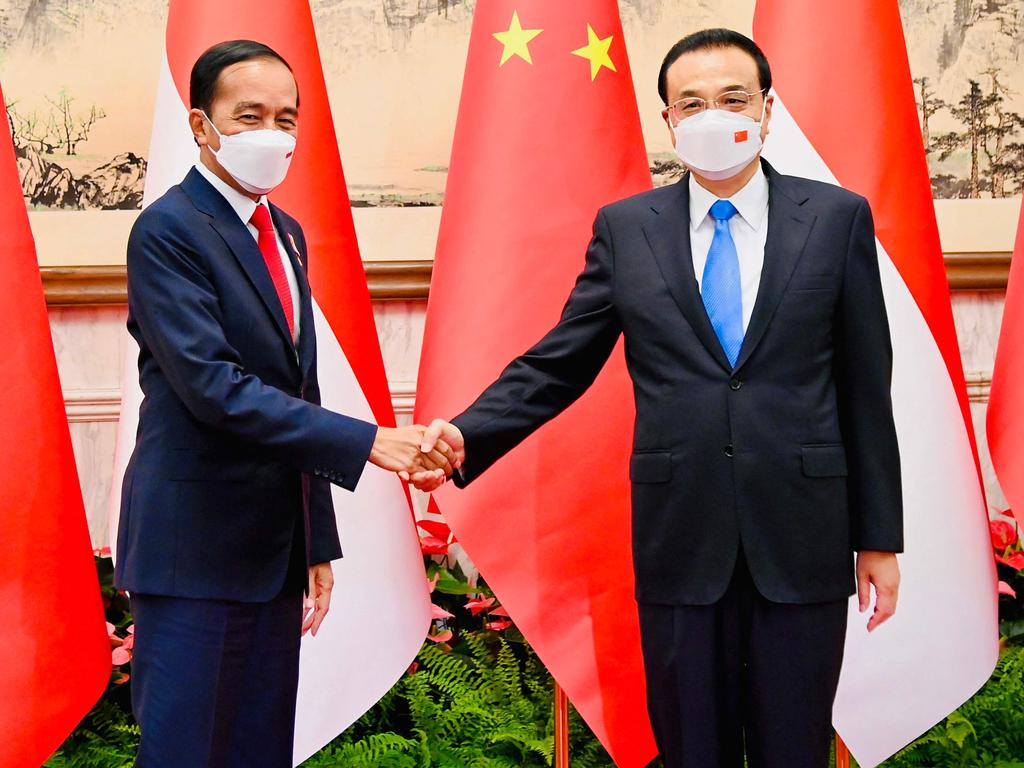

It is possible then that factions could gather before the congress to find, if not an alternative to Xi, then at least a way of pressuring him into curbing his ambitions. The premier, Li Keqiang, is said to be a less nationalist, more outward-looking contender. Xi, though, is head of the party, head of the armed forces, president. His “thoughts” are about to be given canonical status, perhaps turned into a Little Red Book. Getting rid of him would be like extracting four wisdom teeth in one go, without anaesthetic.

These are the dangers ahead in the coming autumn. If there is a botched putsch attempt against Xi he could borrow a ploy used by Mao and Stalin: concoct enemies at home and abroad. Nobody needs that. An overmighty yet insecure leader with a large army impatient for battle – we’ve already got one of those.

The Times

China is preparing for a big geopolitical shift this autumn, one that could turn upside down all our assumptions about Xi Jinping. The plan is for the Communist Party leadership to declare Xi “chairman” – the new Mao Zedong – and in effect a “forever leader”. But what if he falters? What if we have underestimated the depth of domestic opposition to his rule? With Europe engaged in, or touched by, Russia’s feverish war on Ukraine, with galloping energy and cost of living crises, high inflation and lurking recession, the last thing anyone wants is serious instability in China.