British firms face supply chain crisis as China lets Covid rip

Beijing’s decision to relax its zero-Covid policy is hitting British firms’ supply chains once again.

When the Beijing government relaxed its zero-Covid policy last week, David Marr felt a queasy churn in his stomach and considered Chinese philosophy.

“It was a bit of yin and yang to me – on the one hand it felt encouraging, but I’m not sure why they did it,” he said.

Marr’s building products company relies on importing parts from two Chinese factories, both of which are now grappling with soaring Covid infections.

One of his orders, destined for Australia, is currently delayed by eight weeks because half the staff at the Tianjin factory from which he sources steel are sick and unable to work.

“It feels exactly like it did back in 2020 when the virus was first breaking,” he said.

Marr is managing director of Ipswich-based Uni-Prop International, which makes supports for buildings under construction, and is familiar with Covid disruption in the People’s Republic. For six weeks in the summer he could not contact the company in Hangzhou that makes Uni-Prop’s hydraulic system because the area was under Covid lockdown.

“As far as we were concerned, they’d fallen off the planet,” he said.

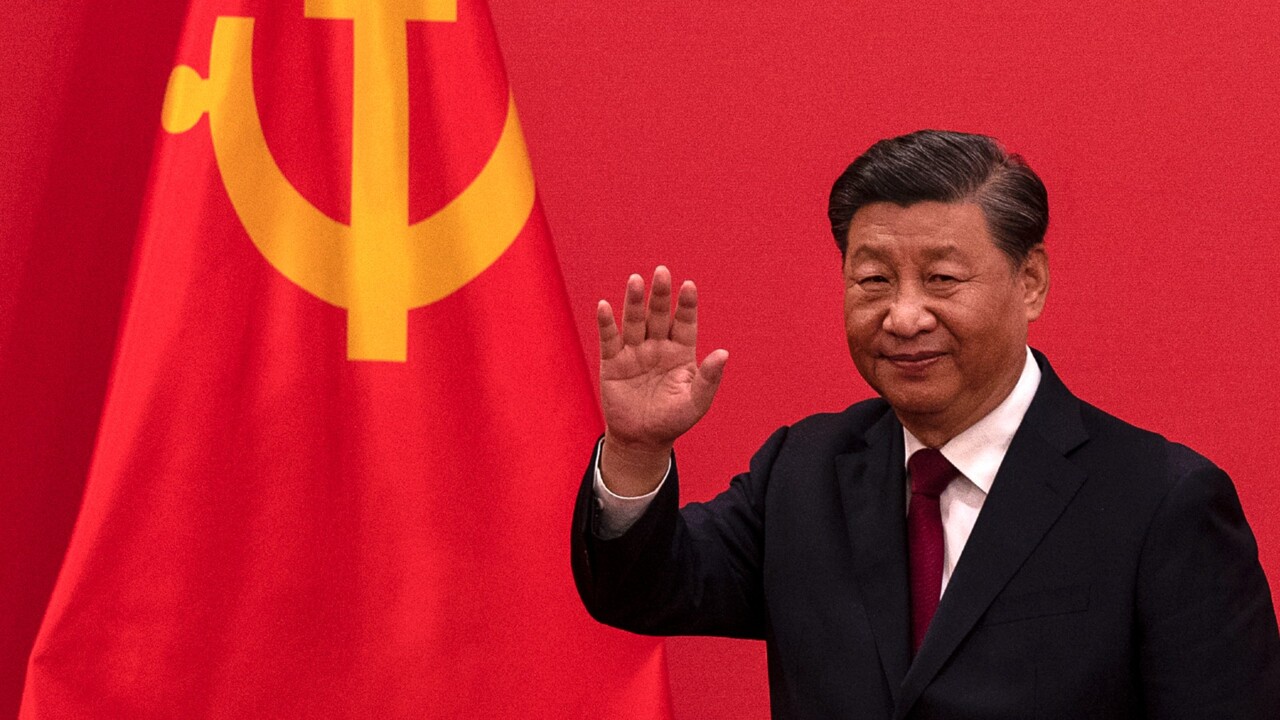

Last week, China announced it would reopen its borders to foreign travellers – the latest relaxation of the country’s strict Covid laws, which have caused political unrest across the country.

China’s decision to fight its Omicron wave with lockdowns rather than vaccinations had led to a halving of forecasts for economic growth. Now, with daily cases approaching one million in some provinces, there are fears that opening up will disrupt industry so much that the economic benefits could be lost.

Sumit Vakil, co-founder of the US-based Resilinc, which monitors supply chains, said: “Companies are preparing for a widespread risk of self-imposed lockdowns.”

Many firms trading in China were building stockpiles in anticipation of disruption.

“If cases continue rising, causing labour shortages and production halts, it will certainly deal a catastrophic blow to the global supply chain,”

Vakil added. “With current inventory levels and planning, the supply chain could handle a two-week production halt, but anything longer than three weeks would cause a ripple effect lasting for months.”

Alan Day, chairman of State of Flux, a supply chain consultancy firm, said that the country’s assembly lines will be overwhelmed.

“I can see it spreading like wildfire in labour-intensive industries such as technology assembly lines, which have multiple people packed together.”

China’s lockdowns have stopped factories developing procedures such as skeleton staff and alternating shift patterns that would let them stay open while reducing transmission of the virus. “In China, they’ve not had the chance to develop that – if you get Covid, you just get locked down,” Day said.

Apple, which makes 90 per cent of its iPhones in China through its Taiwanese subcontractor Foxconn, has been badly affected by worker shortages. Last week, sources at Apple said it had asked Foxconn to start manufacturing MacBooks in Vietnam from mid-2023.

In September, the company moved some iPhone 14 production to India after an outbreak in its Zhengzhou factory led to 23-day delays for US consumers. While currently manufacturing about 5 per cent of its iPhones in India, Apple wants that number to be 25 per cent within three years.

Covid cases are also increasing rapidly in China’s second-tier cities, where a large part of the country’s booming auto industry is based.

Global car production this year is expected to be seven million below its pre-pandemic level, in part because of a lack of Chinese production. Tesla suspended work at its Shanghai plant just before Christmas because of sickness among staff and suppliers, according to an internal notice. In March, BMW had to suspend production in northeast China due to a Covid outbreak.

“China is the most important auto market in the world – almost a third of all car production happens there,” said Tom Narayan, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets.

But he added that Covid uncertainty had forced the auto industry to adapt its global supply chains, with manufacturers sourcing their car parts elsewhere.

“You wind up needing to switch the supply of components to other regions, and there are transport and shipping costs associated with that.”

Still, Ford and Volvo have already started sourcing parts from outside China partly due to surging Covid cases. Mercedes has recently opened operations in Thailand, and other manufacturers are looking to shift tyre production to Vietnam.

Vietnam is watching China’s reopening closely. Manufacturing has been shifting from China to Vietnam since the Trump administration and has accelerated through the pandemic.

“Even without the lockdowns in China, companies would still diversify away from China due to concerns about the US-China trade war and other geopolitical risks,” said Le Hong Hiep, a senior fellow at the Vietnam studies program of the Singapore-based Iseas-Yusok Ishak Institute.

“Covid lockdowns in China only gave them an additional, though temporary, reason to do so.”

Outbreaks of Covid are also disrupting the mining of key commodities needed in auto manufacturing, such as the lithium for car batteries. These elements are almost exclusively mined or refined in China before being exported for car production elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Beijing’s decision to boost trading by ending lockdowns may prove harder to action than envisaged. Large ports such as Ninbgo, Tianjin and Shenzhen have been disrupted this year due to Covid outbreaks, and this has caused significant delays in global shipping.

Viktor Katona, senior crude analyst at Kpler, said the chaos had affected both China and the world economy.

“Clogs at Chinese ports have ripple effects on global supply chains, and this year China’s been a growth hindrance – there have simply been fewer exports.

“Whenever the country flirts with opening up, we see massive upticks in tankers arriving at Chinese ports in anticipation of normal trade resuming. The question is whether the ports can service such demand if Covid spreads through the population.”

But for those companies trading in China under the zero-Covid strategy, the relaxing of laws has at least provided some clarity. In December, British businesses in the country were the most pessimistic they had ever been, according to a report from the British Chamber of Commerce in China. Steven Lynch, a former chairman of the Chamber who conducted the study, said that sentiment “couldn’t get any worse” and that the news was met with “cautious optimism”.

“The overarching message is relief. You now have a bit of certainty heading into 2023 and 2024 – it’s almost like a pressure valve has been released,” Lynch said.

Lynch, who until recently was resident in China, said that every single person he knew in the part of Beijing where he lived had contracted Covid within the past month.

“The second-, third- and fourth-tier cities, where most of the [manufacturing] supply chain sits, have poor levels of vaccination and poor healthcare, and that means Covid is going to have a far larger impact.”

One major UK electronics manufacturer with a factory employing several hundred in China was less pessimistic.

“Two or three weeks ago, it was dire – half the workforce was off with Covid. But they’re nearly all now back at work. There have thankfully been no fatalities. They’re mainly young and we’re hoping it will wash through fairly safely.”

George Magnus, an economist and associate at the China Centre, Oxford University, said that in the long term, the Beijing government’s decision to open up the country to foreign workers will be welcomed by the business community.

“This is definitely a light at the end of the tunnel for international firms that have been hamstrung by not being able to have free movement of their staff and people,” he said. While Magnus agreed that climbing Covid rates would probably continue to disrupt supply chains in the short term, he also believes this should have abated by the spring.

While the country’s mishandling of the pandemic has been a catalyst for firms leaving China, the difficulties they have had pre-date Covid.

“The information doesn’t suggest that foreign companies are spearheading an exodus out of China, but that they are looking to diversify their supply chains and to ‘reglobalise’ to other places where they don’t have the political risk or the geopolitical danger,” said Magnus.

With Covid cases rising and no end in sight, David Marr at Uni-Prop may be joining that group. While he said that no one leaves China lightly, he has started surveying sites in Italy and Bulgaria that could produce his construction products without the Covid disruption

“We’re on a bit of a knife’s edge … China is proving to be a bit more trouble than it is worth,” he said. “Is it better to bite the bullet and make alternative arrangements?”

The Sunday Times