Brexit: Can the UK and EU be friendly neighbours after decades of bickering?

On Christmas Eve, local time, the last element of our post-Brexit trade deal finally fell into place. Much of the past nine months had been dominated by discussion of such arcane matters as “governance”, “ratchet clauses” and “maintenance of the level playing field”. By last week all that was left was to divvy up the herring, mackerel and shellfish.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson hailed a “great treaty” that allowed his country to “take back control of our destiny” and resolve a question that had “bedevilled” British politics for decades. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen “felt quiet satisfaction and — frankly speaking — relief”.

Britain’s relationship with the European bloc began in January 1973 with a wave of enthusiasm, even love, but in the decades since it has often degenerated into distrust, name-calling and open hostility. Maybe it was a mistake to tie the knot in the first place. Or perhaps the breakdown was due to our lack of commitment.

Either way, at 11pm on Thursday (10am on Friday, AEDT) it will be all over. The decree absolute has been issued. The marriage has run its course, and we must think about what happens next. As von der Leyen put it, quoting TS Eliot: “What we call the beginning is often the end. And to make an end is to make a beginning.”

So, are we going to be all adult about it — and pursue what Gywneth Paltrow would call a conscious uncoupling? Or are the prolonged and often acrimonious negotiations merely a foretaste of future squabbles?

The strait between England and France is only 34km at its narrowest point, but it is still wide enough to have engendered a sense of otherness that has long baffled visitors from further afield. An American friend of mine was puzzled recently to hear a British acquaintance say they were “going on a trip to Europe”. “So where are you now?” she asked.

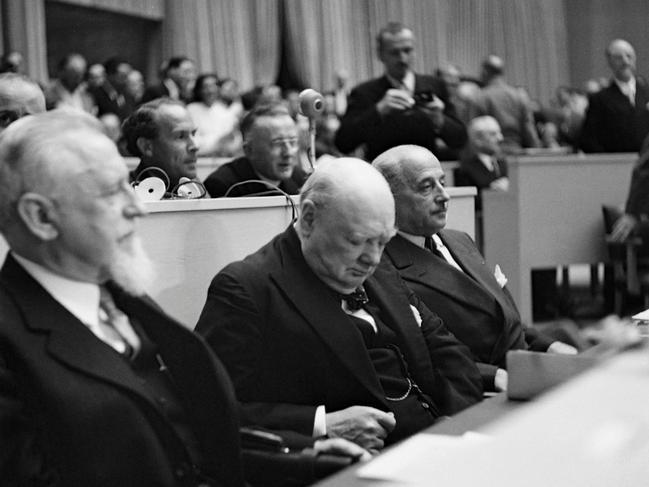

For centuries Britain kept a wary eye on the Continent but remained aloof — intervening only if our vital interests seemed to be at stake. When Winston Churchill called in September 1946 for the creation of a “United States of Europe”, he took it for granted that Britain would not be part of it. Instead, alongside the US and the Soviet Union, we were to be its “friends and sponsors”.

Fast-forward a decade, and we were already beginning to suffer from fear of missing out. Annoyingly, our continental cousins seemed to be getting on fine without us, and President Charles de Gaulle twice vetoed our increasingly plaintive attempts to join their club.

In January 1973, with de Gaulle gone, Edward Heath succeeded in taking us in, but our membership got off to an inauspicious start: Harold Wilson’s Labour government, which came to power just over a year later, wanted to renegotiate the terms and put the result to a referendum.

That November, Helmut Schmidt travelled to the Labour Party conference to extol the virtues of continued British membership. The Anglophile West German chancellor likened himself to “a man who, in front of ladies and gentlemen belonging to the Salvation Army, tries to convince them of the advantages of drinking”.

Yet, when it came to the referendum on June 5, 1975, the remainers won by a resounding 67.23 per cent to 32.77 per cent. Then, as in 2016, support for membership was greater among the more affluent and better educated. Yet it was the old rather than the young who were the most enthusiastic Europeans. Was it because they were the generation who had lived through World War II?

Whatever their misgivings, the young took to membership with gusto. Europe was the future, and it was fun: it was a romantic weekend in Paris or whizzing through the streets of Rome on a scooter. A few, including Stanley Johnson, the prime minister’s father, were so enthused by the “European project” that they took jobs in Brussels. In 1977, Roy Jenkins, a former Labour home secretary, began a four-year stint as head of the European Commission.

The Common Market, as we called it, was also linked with the onward march of democracy: in the mid-1970s, Greece, Portugal and Spain threw off dictatorship and in the following decade were rewarded with membership. The end of the Cold War in the late 1980s paved the way for the entry of Austria, Sweden and Finland — which passed almost unnoticed — and, far more significantly, in the mid-2000s, for the majority of the former Soviet satellites of eastern Europe, too.

Margaret Thatcher, who had campaigned to remain in the 1975 referendum, was a driving force behind the signature in 1986 of the Single European Act, leading to the establishment of the single market — which we will leave on Thursday.

In doing so, she made common cause with Jacques Delors, the dynamic commission president. Yet relations soured after she realised — belatedly — the extent to which the Frenchman saw their joint creation as a stepping stone to more political and economic integration.

The Thatcher years also marked the beginning of the “us” and “them” narrative: with a swing of the handbag and the cry of “I want my money back”, she waged a four-year battle that culminated at the Fontainebleau summit of June 1984 with the award of a budget rebate that in the end was worth about £4bn a year.

In a speech in Bruges four years later she declared: “We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them reimposed at a European level, with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels.” The Sun put it more succinctly in November 1990 in one of its more memorable front-page headlines: “Up yours Delors”.

Then, on September 16, 1992, came Black Wednesday: the loss by John Major’s government of more than £3bn from trying and failing to keep an overvalued pound in the European exchange rate mechanism — forerunner of the euro — showed the perils of tying our currency to those of other countries.

The next year, Major nevertheless signed Britain up to the Maastricht treaty, which heralded “a new stage in the process of European integration”, but only after facing down bitter resistance from the “bastards” on the Eurosceptic right of his party.

It was into this maelstrom that I stepped when arriving in Brussels in April 1995 as a correspondent for The Sunday Times. I was not a particular advocate for European integration. But, with an Italian wife and a foreign-sounding name — courtesy of a Belgian grandfather who had come to Britain before World War I in search of his fortune — I was no little Englander either.

Many of my colleagues — and not just on the tabloids — kept newsdesks back in London happy with fanciful tales about attempts by the European Commission to outlaw bent bananas and harmonise condom sizes. It was difficult not to get sucked into it. The undisputed master of the genre, Boris Johnson, had just returned to London from Belgium after a six-year stint for The Daily Telegraph, during which he cast himself as the scourge of Brussels. To say he was not missed would be an understatement.

There were also serious differences about the future shape of the EU — and more immediate battles. In March 1996 the EU imposed a worldwide ban on exports of British beef in response to BSE, forcing the slaughter of millions of cattle. Major had vowed to put Britain at the “heart of Europe”; instead he found himself waging a war against Brussels.

The arrival of Tony Blair the following year brought a reset: he gave up Britain’s opt-out from the Social Chapter — ensuring new employment rights — and would have signed us up for the euro, too, if Gordon Brown, his chancellor, had not stopped him.

But the referendum Blair promised on the Lisbon treaty, which led to a further move towards integration, never happened. Before the first enlargement to the east in 2004, he also took what was to prove a fateful decision: the UK was one of only three member states (the others were Sweden and Ireland) to open their labour market immediately to workers from the former communist states.

The government predicted 5000 to 13,000 would come to Britain; in the event the figure was more than 20 times that. The middle classes got cut-price Polish plumbers and nannies. The unskilled faced competition for jobs — and began to worry vaguely about a dilution of their national identity.

Attempting to deal once and for all with an issue he felt had been “poisoning British politics for years”, David Cameron promised a referendum on our EU membership; when he was re-elected in 2015 he felt that honouring his promise was “the right thing to do”. His gamble almost succeeded: the difference between the yes and no votes was 1,269,501 — or 1.9 per cent of the population.

Four years and six months on, we will finally experience the consequences of that vote. I got a foretaste during a recent visit to the Eurotunnel complex in Calais, through which 40 per cent of our trade with Europe passes.

Trucks that until now have driven straight out of the tunnel and onto the French motorway network will now face customs and regulatory checks. When each truck leaves Britain, details of its cargo will be uploaded. As it emerges at the other end, a colour will be flashed up in front of the driver on a roadside screen: green means he is good to go; if it is orange, he must drive into the control area.

About €47m ($75m) has been invested in upgrading the 650ha complex and its far smaller counterpart in Folkestone, and countless rehearsals have been held. Will the new system work as smoothly as its operator hopes?

“We have spent the past four years working with our customers across Europe, educating them,” said John Keefe, director of public affairs for Eurotunnel, who took me on the tour. “Those who drive the lorries get it. The big question is whether the traders who are sending the goods have fully understood. And that’s one of the big outstanding questions.”

The real test, he believes, will probably come in the second week of January, when the holidays are over. In the meantime, the fragility of our links with the Continent have been demonstrated by the chaos last week when France decided to close the border for 48 hours in response to the new coronavirus strain. More than 4000 unfortunate truck drivers spent Christmas in their cabs.

Companies that trade with Europe will have to contend with new rules they have had precious little time to digest. Many a devil will be found lurking in the 1200 pages of the agreement’s detail. Those holidaying on the Continent will face a host of minor irritants. The freedom to live and work and study in Europe will disappear. Taking back control of our borders means the EU gets back control of its borders, too.

Sovereignty — and leaving the single market Thatcher helped to create — also comes at a cost. The Office for Budget Responsibility has estimated Brexit will reduce Britain’s GDP over the next 15 years by 4 per cent. Yet the reliability of such predictions has been shaken by COVID-19, which, according to the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics, has shrunk the economy by 8.6 per cent over the past year. Much will depend on how we take advantage of the new freedom of manoeuvre brought by taking back control — which is where things grow hazy.

The government has been so preoccupied over the past months with negotiating the deal — and firefighting against the pandemic — that it has failed to spell out a coherent vision of the future, let alone tried to sell it to us.

Yet, whatever vision we follow, nothing will alter the geography that binds us with the Continent. Which means that, like any divorced couple obliged to stay living close to one another, our paths will continually cross. When we do, we will look back at the years we spent together — and I hope we remember the good times as much as the bad.

The Times

As with any relationship that has gone sour, in the end it was all down to haggling about the little things that mean so much: in this case, fish — £597m ($1.06bn) of it. A big deal for the fishermen of Grimsby or Brixham, admittedly, but a drop in the ocean compared with the £294bn of goods Britain exported to Europe last year, or the £374bn of goods the UK bought.