Billionaire rocket men have set us on course for conflict in space

If you’re into one-upmanship, nothing quite beats the space race. But there are consequences beyond a bunch of macho tax-exiles taking selfies from space.

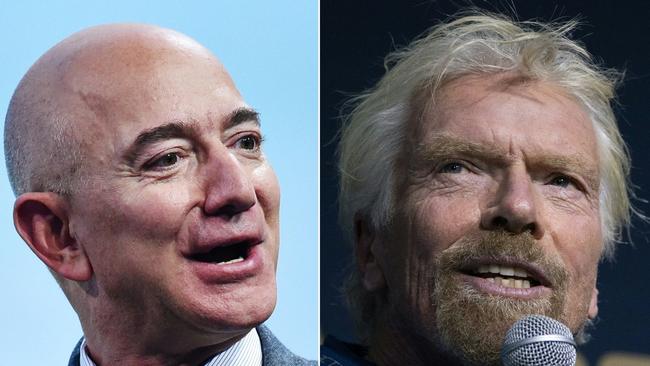

Let’s be honest, Richard Branson, it’s about the bragging rights. If you’re into one-upmanship, nothing quite beats the space race. The planned launch early on Sunday US time (Sunday night AEST) from the site near the town of Truth or Consequences in New Mexico of his Virgin Galactic rocket plane VSS Unity, with him aboard, should see Branson beating the Amazon boss Jeff Bezos into space by nine days.

Nine days! Bezos’s New Shepard, when it eventually gets up there, will offer passengers 11 minutes of weightlessness, compared with four minutes of floating time on Virgin Galactic. Bezos also has bigger windows.

When Tesla’s (and SpaceX’s) Elon Musk won a contract from NASA to develop a lunar lander, thus getting big-time establishment approval as a space player, he tweeted his losing rival Bezos: “Can’t get it up [to orbit] lol”. It’s all very locker room and, for those of us whose net wealth falls below the $US1bn ($1.3bn) entry ticket you need for a cosmic start-up, a trifle embarrassing.

You have to struggle to believe that this is more than a test of manliness, that there’s a deeper intellectual passion. It can’t be, surely, that the space tourism market of the future is so enormous that there’s room for three players, three rocketeers, with an urge to burn off their hard-won fortunes.

It’s partly a shared sense that space is the new frontier, that there are ways of deploying their hunger for risk in the honourable cause of expanding knowledge about the universe. They have been separately pondering space travel for decades.

Branson talks of a 17-year-old dream about to come true. His VSS Unity has reportedly conducted more than 20 test flights. Musk came to the rocket business after selling his online payments company PayPal and was talking about colonising Mars as soon as he gets engineering right. Cheap rockets could, he argued, help turn humanity into a “multi-planetary space-faring civilisation”.

By the time Branson took him out for dinner in 2011, Musk had already made his mark: he had launched the first privately built liquid-fuel rocket into orbit using a two-stage liquid-fuel system. And he had already propelled a commercial satellite into orbit. Branson wanted to know whether they could co-operate. Musk wasn’t sure whether there was anything in it for him and didn’t shake hands. He went out drinking with friends but as Nicholas Schmidle tells it in a remarkable new book about the modern space race, Test Gods, “he ended up at the bar, by himself, reading a dusty Soviet rocket manual”.

The favourite reading of the three rocketeers, though, was Tom Wolfe’s extended 1979 reportage The Right Stuff, about the early space race. It was told through the eyes of a group of ace US fighter pilots who transferred their skills to space travel. “I was curious,” said Wolfe, “as to what makes a man willing to sit on top of an enormous Roman candle and wait for someone to light the fuse.” This convinced Musk and Bezos that the concentrated resources put behind the 1969 moonshot were the making of a new breed of heroes who could give the country a mission and establish beyond doubt that the US had the technological edge.

Branson, like Musk, was taken by the flight term “pushing the envelope”. After publication of The Right Stuff the phrase became a commonplace way of describing anything that involved some extra effort. But Wolfe had a very precise interpretation: “The ‘envelope’ was a flight test term referring to the limits of a particular aircraft’s performance, how tight a turn it could make at such-and-such a speed and so on. ‘Pushing the outside’, probing the outer limits, of the envelope seemed to be the great challenge and satisfaction of flight test.”

That resonated with the three rocketeers. The pushing to the extremes is what had motivated the two Americans and was part of Branson’s biography of constant reinvention. More, it helped them individually to see NASA, set up by the US government to counter the Russian challenge in space, as an over-bureaucratised, over-cautious organisation, one that was slowing down the process of space exploration.

Musk in particular was frustrated by the way that US government contractors were overspending, “building a Ferrari for every launch when it was possible that a Honda Accord might do the trick”.

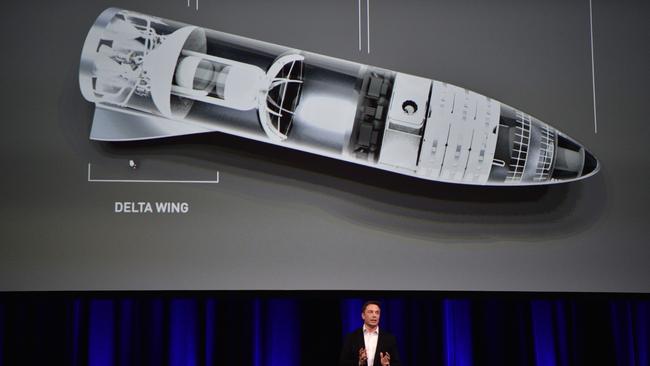

Little wonder that he was gleeful when he sold the idea of his lunar lander to NASA or showed, in a test flight in May, that he could launch a huge Starship rocket, designed to be the biggest since Saturn V took the Apollo team to the moon, fly it 10 kilometres above Texas, then land it unscathed.

The astro-billionaires have slightly different aims but agree on a central point: the resilience of the West hinges on the nimbleness of tech entrepreneurs to innovate quickly rather than trail around committees. The first question they have to address is: manned or unmanned space flight? Space exploration, which can be conducted by increasingly sophisticated robots, or human colonisation with its undertones of conquest and boots on the ground? Only when that is resolved will it become clear whether the space race is being driven by scientific curiosity or by politics and the vainglorious ambition of the super-rich.

NASA is on the hunt for a lunar base that can guarantee light, elevation and frozen water. It faces competition from a planned joint Russian-Chinese lunar research station which should be ready for crewed visits by 2036. Establishing even a basic outpost is a grinding, costly affair. Robots have to excavate rock samples and return them to Earth for a decade or so until the optimal site is found. Unmanned ships then have to transport the construction materials and more robots have to assemble them. Eventually the humans turn up.

How do you sustain public interest and public funding for such a lengthy period? NASA has been losing its dominance over the conversation about post-moonshot exploration. It is difficult to compete against the nifty low-cost space initiatives of free-spirited entrepreneurs. George W Bush planned to build a lunar outpost run by humans working six-month shifts between 2019 and 2024. Never happened. Musk, by contrast, says SpaceX could have a first crewed mission on Mars as early as 2024. Maybe that won’t happen either but he has caught the popular imagination, effectively declaring Mars to be sexier than the moon.

NASA, meanwhile, plods its worthy path. It plans a politically correct trip to the moon, a woman astronaut, a culturally diverse candidate perhaps. As for Mars, it is busily mapping the place and naming hills after scientists who have died of Covid-19. It’s not that government is talking itself into irrelevance. The US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) has been demonstrating how the state can benefit from working with private enterprise.

Set up by Washington in 1957 after the Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite alerted the Pentagon to the speed of the enemy’s technological catch-up, Darpa became the Pentagon’s brain. It didn’t run its own labs but spent most of its cash on university and industrial researchers who were on the cutting edge.

Darpa came up with funds, effectively venture capital, but typically gave the researchers only six months to prove that the sponsored invention was viable and of use to the military. Among the offshoots of its projects were the early internet – dubbed, rather ambitiously, the intergalactic computer network – email, weather satellites, lasers, night-vision glasses and the Saturn V rockets.

The attraction of space for commercial ventures is clear and it’s not really about the romance of the heavens. Nor is it about weightless jollies. It’s about understanding the world’s growing dependency on satellites, making them cheaper to produce and launch, and leveraging data gathered in space.

Space data can create new markets: farmers can be guided as to what to plant. Low-priced small satellites can show emergency services how forest fires are spreading or which rivers are rising. There are humanitarian uses, including the tracking of ethnic displacements.

Some of this information is available to governments: the US, Russia, China, France and India mop it up. But commercial use of low-priced small satellites can take the initiative away from states and create new, quick ways of solving crises. That is what is meant by the rather cheesy slogan, “the democratisation of space”.

Musk’s competitors are worried that SpaceX’s Starlink service puts it on course to build the biggest ever satellite network. Its 1500 existing satellites make up about a quarter of all those in orbit. There are plans for 10,000 more.

Musk, of course, has deep pockets and there’s no doubt that space is looking very crowded as even mini-states and universities look for eyes in the sky. Betting on an ever-widening market for cheap space data remains quite a gamble. “If you give that technology out and make it more accessible, people will start doing all sorts of things, many of which never take off,” says a senior analyst at a US space consultancy. “But they may end up being the next Google or Instagram.”

This could be the gold at the end of the rainbow for the astro-billionaires. Whether commercial, manned space travel serves this cause is another matter. It dodges the main questions about outer space, not just how the mass of information buzzing overhead should be processed and by whom but how to avoid the weaponisation of that data.

Stanislaw Lem, the late Polish futurologist, wrote a science fiction novel called Peace on Earth in which all weapons of mass destruction are spaceshipped from Earth to the moon and then divided between sectors by a lunar agency. It doesn’t end well, not for Earth nor for the moon.

Lem had spotted (this was the Cold War 1980s) that a militarised space could never be a way of solving Earth-bound conflicts. Surveillance from space could be presented, even now, as a net gain for humanity.

But the problem is one of hostile intent or perceived hostility. All the signs are that countries like Russia, China and the US are ploughing their resources into anti-satellite satellites, exploring not the mysteries of the universe but rather the puzzle of how to shoot down or blind each other’s orbiting tech. All three states (Britain too, now) have their own space forces with flashy uniforms. Space has been recognised as one of the domains of terrestrial war.

In early 2001, eight months before 9/11, Donald Rumsfeld warned of the possibility of a space Pearl Harbor, a first-strike attack on US space systems.

He had been the head of a commission to assess US national security threats of the future; he had grown impatient with the complacency surrounding the collapse of the Soviet Union, the apparent self-destruction of Washington’s primary enemy. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 was, he said, “a failure of imagination. We didn’t know what we didn’t know, that they [the Japanese] could do what they did in the way they did it.”

No one paid much attention in the US, certainly not after 9/11 and Rumsfeld became George W Bush’s defence secretary at the helm of the war against terror. But he didn’t stop worrying about war in, or from, space and it has become part of the discourse in the strategic community. After all, both China and Russia have set up co-orbital satellites capable of tailgating sensitive US satellite constellations. They can latch on to Western satellites and shove them off their orbit, rendering them deaf and dumb as well as blind.

The Soviet Sputnik scared the wits out of the West in the 1950s. It showed that a nuclear Moscow had the capacity to deliver an intercontinental ballistic missile. The US understood that its technical superiority could no longer be taken for granted.

Maths and science education was updated. In Britain, maths scholars were encouraged to read Russian works in their field and report back if they spotted any unusual research subjects. The Russian and Chinese militaries experienced a similar wake-up call in the Gulf War of 1991 when the widespread American use of GPS in the deserts of Kuwait and Iraq sent Saddam Hussein’s soldiers fleeing. A modest device, already used by hikers, became a war accelerator and made Russian generals think long and hard about electronic warfare, how to deploy jamming devices and ultimately how to disrupt GPS satellite constellations.

In the US, meanwhile, Darpa has been assigned the task of finding an alternative to GPS dependency for US troops. Fifth-generation aircraft, more autonomous and remotely piloted vehicles – the essence of 21st-century warfare – are dependent for their communications, navigation and intelligence on a feed from satellites.

Knock out a constellation and you will have changed the balance of power on a terrestrial battleground. Space then is an ambiguous war domain and adds to the complexity of generalship; it enables a faster pace of military operation, it feeds more up-to-date information into the fighting calculus but it introduces new vulnerabilities.

The more that space is militarised, the more debris and sat-waste that is scattered, the less sensible it becomes to fill the heavens with humans. A better use of resources is to boost research and development funding into cutting-edge dual military and civilian use technology.

In 1964 the US was spending 1.86 per cent of GDP on R & D. That had dropped to 0.83 per cent by 1994. In that same period US corporate R & D investment nearly doubled as a percentage of GDP. What had happened was that government labs outsourced to corporate America. Then the large companies spent less on R & D and bought up smaller venture-backed tech companies. That created wealth but it did not particularly boost US national interests.

In China, Beijing has pushed up its global share of technology spending from 5 per cent in 2000 to 23 per cent in 2020. Many of its commercial technologies have strategic applications – 5G, quantum computing, biotech, AI – and they are handing Beijing the edge.

At this rate it will overtake the US in 2025. This is the real race of the moment, rather than the contest between very-rich-ageing-men-in-their-flying machines. Interstellar travel does fascinate, engages science fiction writers and cinemagoers, and has a particular charm now, when it is a struggle even to get to Mallorca. But it will take generations of Musks and Bransons, of trial and error, before the dream approaches reality. Even then we may be asking what it all amounted to, whether really it was just about a bunch of macho tax-exiles taking selfies from space. We need their brains, their enterprise and vision right here on Earth.

Roger Boyes is diplomatic editor of The Times

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout