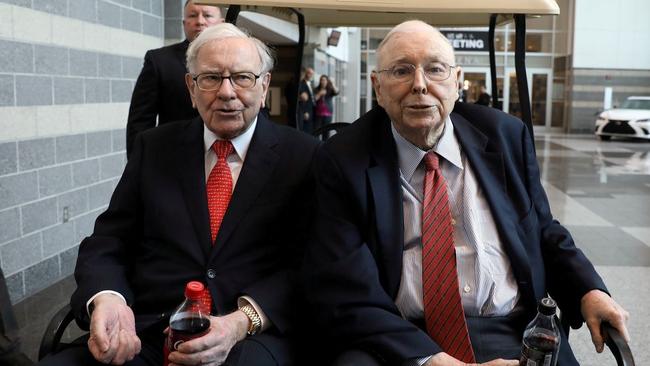

Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger still calling the shots

Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger were a united force at their annual meeting in Los Angeles.

The streets of Omaha typically come alive during the so-called Woodstock of Capitalism, welcoming the tens of thousands who flock to hear from Warren Buffett. But these are not typical times.

Twelve months ago, when the pandemic prompted Berkshire Hathaway to shift its annual meeting online for the first time, one absence was felt more acutely than any other. Charlie Munger, Buffett’s right-hand man and the conglomerate’s vice-chairman since 1978, did not travel to the city in Nebraska.

This weekend, forced once again to hold a get-together without the masses, Buffett, 90, was not prepared to do so without his deputy. And so the pair addressed shareholders live from Los Angeles — where Munger, 97, lives. For one year only, the Sage of Omaha became the Savant of California.

Berkshire was a struggling Rhode Island textiles business when Buffett bought it in 1965. He used it to buy insurance companies, creating a cash pool from the premiums, which he used for further investments. It now owns dozens of firms and a $US282bn ($365bn) investment portfolio. Buffett, worth more than $US100bn, has promised to donate most of his wealth to charity when he dies.

Having made his first investment almost eight decades ago, aged 11, Buffett opened Saturday’s meeting with a warning to the influx of day traders dipping their toes into the market.

“There’s a lot more to picking stocks than figuring out what’s going to be a wonderful industry in the future,” he said, noting that some 2000 automobile companies were established in the 20th century. “In 2009 there were three left, two of which went bankrupt.”

However, as he dished out advice to fledgling investors, Buffett faced questions over his own decisions. Berkshire, which for decades outperformed the S&P 500, has slipped behind Wall Street’s benchmark share index in the past five years.

He defended the conglomerate’s activity during the pandemic, including its sale of stakes in major airlines. Shares in carriers have since recovered significantly.

Berkshire also reduced its positions in leading banks and did not make a large acquisition. He conceded that selling some Apple shares was “probably a mistake”, however. Berkshire’s stake in the iPhone maker remains significant, comprising about 39 per cent of its total declared investment portfolio.

Buffett also admitted his surprise at America’s “red hot” recovery. “This economy right now, 85 per cent of it is running at super-high gear.”

Critics assert that Berkshire is struggling to keep in step with the times. Buffett, who controls almost a third of the voting power, ensured two motions were easily defeated.

The first, supported by just over 25 per cent of votes cast, called on it to publish annual reports on its climate change efforts.

The second, which won the backing of 24 per cent, proposed greater disclosures on diversity. Although Buffett does not dispute the importance of either issue, he said such group-wide requirements would be “asinine” for a vast conglomerate built around autonomy.

He expressed an aversion to “moral judgments” on stocks — “If you expect perfection in your spouse, or in your friends, or in companies, you’re not gonna find it” — and said he had “no compunction” about owning shares in Chevron, the oil group.

His business partner, not known for biting his tongue, concurred.

“I don’t think we think we know the answer to all these questions about global warming,” Munger said. “The people who ask the questions think they know the answers. We’re just more modest.”

Buffett’s enduring partnership with Munger has long been a key draw for Berkshire’s loyal legion of disciples. They claim to have not had an argument in six decades. Asked at one point about conflicting opinions, Munger stressed they “don’t have to agree on every damn little thing”.

Those who logged in for Saturday’s meeting were left in little doubt of the strength of this alliance.

Pressed about his admission that Berkshire paid too much for Precision Castparts — $US32.1bn, to be precise — in its largest ever acquisition in 2016, Buffett suggested he would “continue making mistakes”. Munger retorted: “The rest of us will help.”

They remain in charge, but a new generation of leaders is lined up. Ajit Jain, who heads Berkshire’s insurance business, and Greg Abel, who oversees its energy arm, were both on hand to take questions. Their double act may need refining.

“Every quarter we will talk to each other about our respective businesses,” Jain, 69, said somewhat blandly of his “perfectly well-functioning relationship” with Abel, 58.

Then again, during a four-hour session, Buffett and Munger — fuelled by Diet Coke and peanut brittle — signalled no interest in walking away.

“I would like to point out that in three more years Charlie will be ageing at 1 per cent a year,” Buffett joked. “We will have the slowest ageing management, percentage wise, by far, that any American company has.”