Beijing security law forces Amnesty to pull out of Hong Kong

Amnesty International will close its offices in Hong Kong as fears grow of ‘serious reprisals’ under the city’s national security law.

Amnesty International will close its office in Hong Kong as fears grow of “serious reprisals” for staff under the territory’s national security law.

The group, which backed Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement before Beijing’s law criminalised dissent, said that its offices would close before the end of the year.

“This decision, made with a heavy heart, has been driven by Hong Kong’s national security law, which has made it effectively impossible for human rights organisations in Hong Kong to work freely and without fear of serious reprisals from the government,” Anjhula Mya Singh Bais, who chairs Amnesty’s board, said.

“The environment of repression and uncertainty created by the national security law makes it impossible to know what activities might lead to criminal sanctions.”

The Beijing-backed legislature implemented the security law last year after months of anti-government protests. Since then more than 120 people have been held under the law, and other democracy activists have fled.

Finn Lau, one of those who have left, said the departure of Amnesty would make it “almost impossible” for smaller civil society groups to operate. “The draconian national security law brings much more than a chilling effect to Hong Kong,” he said.

Most of the prominent pro-democracy activists are in jail for taking part in unauthorised assemblies. Dozens of political organisations and trade unions have ceased operations out of concern for personal safety under the law, which erodes freedoms promised when the British colony was handed to China in 1997. Dr Bais said: “It is increasingly difficult for us to keep operating in such an unstable environment.”

A Hong Kong demonstrator, nicknamed Captain America for wielding the superhero’s shield during protests, was found guilty on Monday of incitement to secession. Ma Chun-man, 31, held up placards and gave media interviews during 20 protests last year.

Stanley Chan, a district court judge, said: “Such a clear political stance has undoubtedly made people believe that the defendant had the intention to incite secession. The defendant has constantly and unreservedly incited things that are forbidden under the national security law.”

Hong Kong had previously served as a hub for human rights workers in Asia, drawing charity groups with the freedoms promised under the handover agreement. A number of other leading non-governmental organisations, including the New School for Democracy, have now moved to Taiwan.

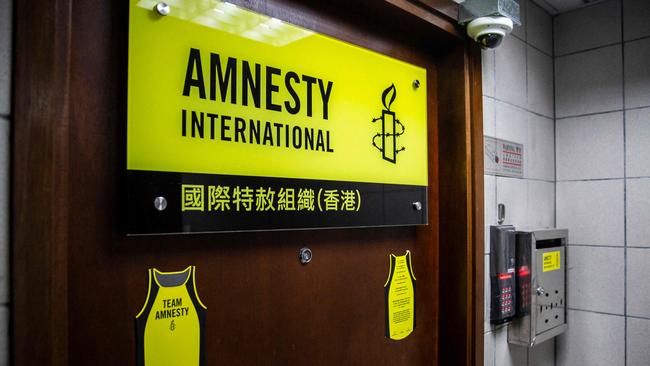

Amnesty, which had an office in the Kowloon district of Hong Kong, said that Beijing’s law used a “sweeping and vaguely worded definition of national security, arbitrarily as a pretext to restrict human rights”. In August, Amnesty described the closure of the most prominent pro-democracy group, the Civil Human Rights Front, as a “worrying domino effect”.

Joshua Rosenzweig, head of Amnesty’s China team, said: “Along with political parties, media outlets and unions, we sadly now must add NGOs to the list of those targeted simply for doing their legitimate work.”

Mark Daly, a human rights lawyer, told the South China Morning Post that Amnesty’s decision spoke “volumes about Hong Kong’s downward spiral with respect to the rule of law”.

The outcry was not universal, however. Holden Chow, a pro-Beijing Hong Kong politician, said: “It is outrageous for any organisation to smear the national security law by unnecessarily closing their branches here.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout