The purging of unacceptable thought on university campuses on both sides of the Atlantic shows no sign of abating. Ancient cloisters and postmodern concrete halls alike are home to safe spaces and trigger warnings, a cultural orthodoxy enforced by a growing army of overprivileged, hypersensitive little Maoists, in league with a vast bureaucracy of university administrators and, if they’re not already fellow-travellers, a cowering, cringing faculty, terrified of being outed on Twitter for an offhand remark at a wine-and-cheese social.

But from the US this week there’s hopeful news at last of organised resistance. A group of distinguished academics, accompanied by some high-profile writers and others, have taken a small, bold step towards restoring the ancient ideal of a university by birthing a brand new one. The University of Austin, as it calls itself, named for the capital of Texas in which it will take physical form, states in its foundational declaration its commitment to a “fearless pursuit of truth”.

Its first president, Pano Kanelos, a Shakespeare scholar and formerly head of St John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland, said in an inaugural statement that illiberalism had become a “pervasive feature of campus life” – “So much is broken in America, but higher education might be the most fractured institution of all”. The university plans to open its doors to students next year with a program entitled “Forbidden Courses”, and then admit graduate students and eventually undergraduates.

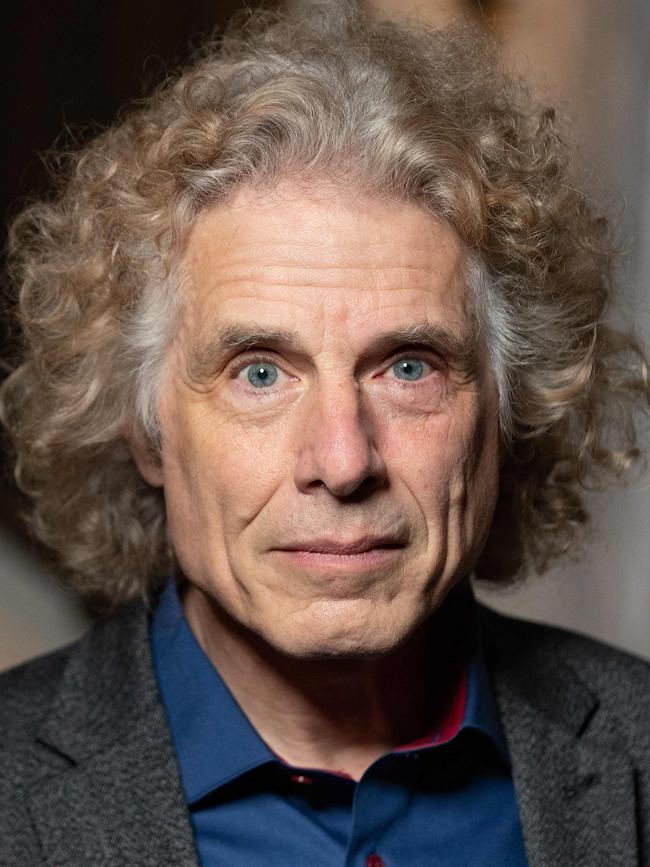

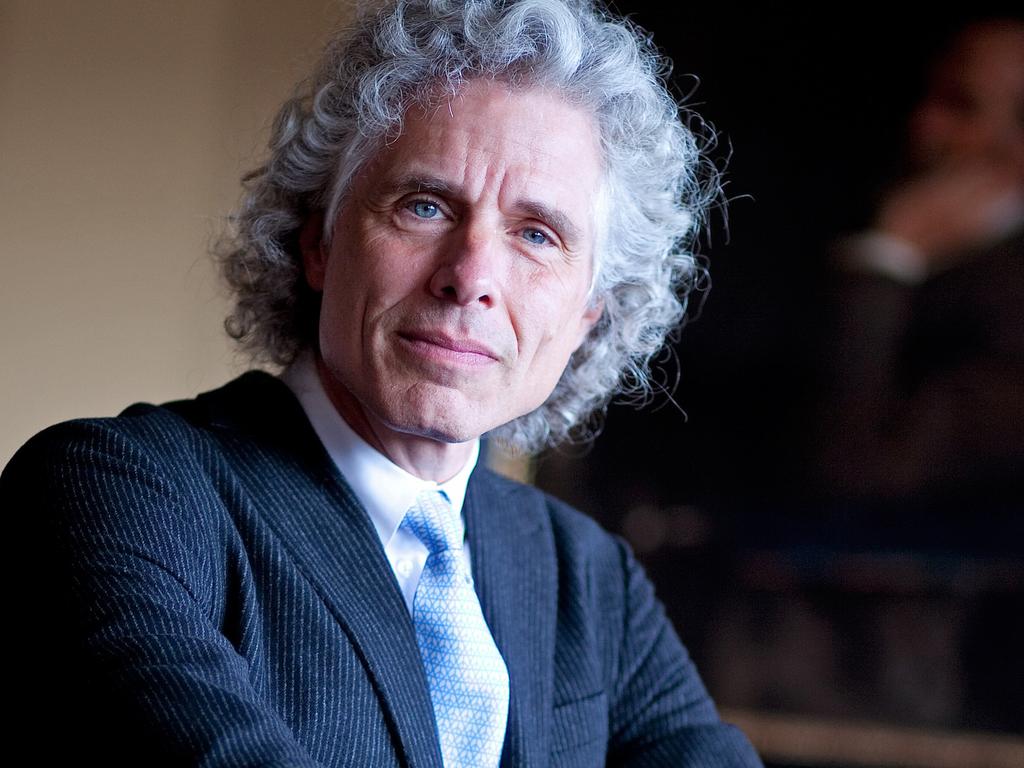

The names of those associated with the new institution read like a modern-day index of prohibited authors. Peter Boghossian recently resigned from Portland State University after a sustained campaign of harassment against him over his work. Steven Pinker, the famously hirsute Harvard psychology professor, who has been a target of students and academics for alleged racial insensitivity, is an adviser. Niall Ferguson, the Scottish-born historian, who has been under attack for years for unfashionable views about empire and other subjects, is a prime mover in the creation of the college.

Another adviser is Lawrence Summers, the economist and top official in two Democratic administrations, who was ousted as president of Harvard after a run-in with feminists over debating gender differences in mathematical aptitude. Kathleen Stock resigned from the University of Sussex last month after a campaign of vilification for supposedly transphobic views.

Other universities have been launched in the US in the past half century with similar goals, many of them with explicitly religious identities for those seeking their own freedom away from the oppressive progressive secularism of the modern campus. The creators of the University of Austin are consciously trying to avoid this. They have no religious affiliation and stress their absolute commitment to a non-ideological environment.

The announcement got the predictable raspberry from those in academia and the media who, with no evident irony, see it as their job to enforce the boundaries of speech. It was lampooned as “Trump University” by critics on the left, an absurd designation for a body whose founders include the likes of Summers and Pinker, among many notable liberals.

The ludicrous critique, in fact, merely makes the founders’ case for them: the idea that any dissent from the orthodoxy can only come from dangerously right-wing partisans. In its opening declaration the university cites the now-familiar litany of statistics that attest to the astonishing monocultural conformity of modern universities. Nearly a quarter of academics in humanities and social science support ejecting a colleague for having wrong views on topics such as immigration. More than a third of conservative academics say they’ve been threatened with disciplinary action for their views.

As welcome as the new institution undoubtedly is for those who favour a real liberal education, what are its prospects? As one of the academics associated with it acknowledged to me, breaking the stranglehold of American universities is a tough challenge. A list of the top ten US universities today is almost identical to what it was 50 years ago.

The problem is not just the gargantuan financial resources these colleges have amassed – Harvard’s endowment was recently valued at more than $50 billion – it is that they have become massive credentialling bodies as much as centres of study and research. What you learn at Harvard is probably less important for your life opportunities than the fact that you went there.

Whatever misgivings they may have about the constraints on free thought at these universities, will bright, ambitious young men and women risk passing them over for the freedom of an institution most of the world has never heard of?

The founders are hopeful that this may be changing. In the US, perhaps more than the UK, there are myriad success stories of those who never attended any university, let alone an elite one. What’s more, in a start-up age, when a company that didn’t exist 30 years ago can become the largest in the world, why shouldn’t the culture of disruption take root in education?

There’s not much ivy in Austin, nor a single dreaming spire. There are lots of thriving tech companies in a welcoming environment of innovation. True intellectual freedom feels like an innovation these days, too.

The Times

Oxford was once, in the words of Matthew Arnold, the home of lost causes, and forsaken beliefs, and unpopular names, and impossible loyalties. In most of today’s universities in the English-speaking world a display of such heterodoxy would almost certainly get you, in quick succession, a campaign of vilification by undergraduates, censure by academic colleagues, public shaming by the authorities and a new career as an occasional online controversialist.