Astronomers capture ring of fire around Milky Way’s massive black hole

The stunning picture offers humanity its first view of the Milky Way monster known as Sagitarrius A*, and was made possible by a single ‘Earth-sized’ virtual telescope.

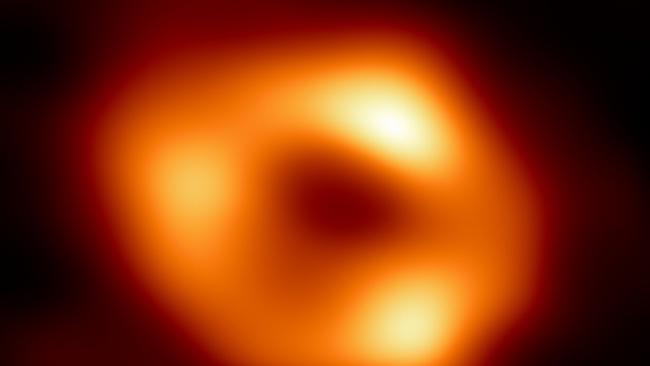

Scientists have captured the first image of the giant black hole that lurks at the centre of our galaxy, revealing the “ring of fire” that surrounds its dark heart.

For decades researchers had watched stars circle something invisible, compact and massive at the core of the Milky Way. The strong presumption was that this object – known as Sagittarius A* (pronounced “A-star”) – was a black hole. The new image provides the first direct visual evidence.

A black central region, known as the shadow, is surrounded by a bright ring-like structure, composed of ultra-hot plasma and gas. This glowing halo swirls around the black hole’s event horizon, the boundary beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape its gravitational pull. “What we see looks like a ring of fire – it fits beautifully with Einstein’s predictions,” said Dr Ziri Younsi of University College London, who is part of the global collaboration of scientists responsible for the picture.

Nobody knows how black holes form, though one idea that astronomers will hope to test with the data from this project, and other instruments including the new James Webb telescope, is that they are primordial relics of the Big Bang.

The same coalition of about 300 scientists was responsible for the first image of a black hole, released in 2019. It depicted an object called M87, which lies at the centre of the distant Messier 87 galaxy and has a mass equivalent to about 6.5 billion Suns.

Sagittarius A* is much less massive – equivalent to about four million suns. It lies about 27,000 light-years from Earth, which means it appears to us to have about the same size in the sky as a doughnut would on the moon.

To capture the image, the team created what is known as the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). This linked eight existing radio observatories, spanning the Antarctic, Europe, Africa, North America, South America and Australia, to form a single “Earth-sized” virtual telescope.

It is sharp enough to read the lettering on a 10 pence coin in London from 3500km away in Cairo.

Though Sagittarius A* is far closer than M87, it is much smaller, which made it more difficult to capture an image.

“The gas in the vicinity of the black holes moves at the same speed, nearly as fast as light, around both [Sagittarius A*] and M87,” said Chi-kwan Chan of the University of Arizona. “But where gas takes days to weeks to orbit the larger M87, in the much smaller Sgr A* it completes an orbit in mere minutes.

“This means the brightness and pattern of the gas around Sgr A* was changing rapidly as the EHT Collaboration was observing it – a bit like trying to take a clear picture of a puppy quickly chasing its tail.”

Ultimately, researchers believe better data on black holes might offer a path towards a new theory of quantum gravity – a means of uniting Einstein’s theory of general relativity, which explains the universe on a large scale, with its discordant cousin, quantum theory, which explains the behaviour of subatomic particles.

For now, it may help perhaps to rehabilitate the public image of black holes. “These objects do not only destroy and kill,” Dr Younsi said. “They are responsible for holding galaxies together. Without them the universe as we know it wouldn’t exist.”

The EHT team’s results are being published in a special issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout