He could not have been more out of touch with his own people. Only two weeks later, huge demonstrations against his rule erupted and his violent reaction to them began the long war in which half a million people have died. I was one of the last western ministers to visit him before his actions went beyond the pale, urging him in vain to find a better way forward for his country than dependence on Russia and Iran.

It was the second time I had been to his hilltop palace for a lengthy talk, bemused by the always ridiculous surroundings of an authoritarian leader: I was driven up a long private highway, walked hundreds of yards along a vast red carpet and then sat with him by the plate-glass windows through which he watched the teeming, allegedly loyal, citizens of Damascus below.

The first occasion, two years earlier, had been more hopeful. Assad had listened to my argument that Syria could be more prosperous if it had good relations with the West, even venturing the thought himself that the long-running stand-off with Israel over the Golan Heights could be settled.

Meeting Assad could be deceptive because he was conversational and polite as well as westernised by his medical training in Britain. His wife is British-born – I also went to her separate, more homely, hilltop vantage point to repeat the message that Syria could change direction. But he came across as a likely case of impostor syndrome, of trying to look capable in the seat his tyrannical father had occupied and where his deceased elder brother was meant to have been.

Assad seemed as much a captive of the power of his family and their Alawite sect as in charge of them. He was evidently not capable of pursuing any vision of Syria’s future away from the power bases of Moscow and Tehran. This is no excuse for him – a moral man would have walked away rather than have slaughter and atrocities carried out in his name. But he lacked the boldness even to do that.

Assad succumbed early on to the dictator’s curse: living within such secure surroundings and so many protestations of loyalty that they cannot spot their imminent collapse. Now his rule has ended as most dictatorships end, with the frantic dash to an airport hours before those devoted citizens smash down the palace gates. Many more of today’s autocracies – Putin take note – are likely to end the same way. Assad had the opportunity to take Syria in a more open, liberal direction but could never bring himself to risk it.

The tragedy of the long civil war since then has been exacerbated by other missed opportunities on the part of outside powers. As UK foreign secretary I worked hard, alongside the US, to deliver the Syrian opposition factions into peace talks in Montreux in 2014. We had agreed with the Russians on a plan for a ceasefire and power sharing. But Moscow never pushed Assad to seal the deal, since Putin saw the chance for Russian forces to move in and make his bases in the Mediterranean permanent through a bloody intervention the West would not challenge.

Putin knew that, because we had missed our own opportunity and lost our credibility along with it. Having stated that the use of chemical weapons by Assad would be a “red line”, President Obama failed to act when the line was clearly crossed and the House of Commons voted down our intention to use military action when faced with such a crime. Our ability to influence events evaporated.

There are many lessons here: dictatorships unravel slowly at first and then collapse very quickly; doubling down on war instead of compromise can lead, as Moscow must contemplate this week, to losing everything; well-intentioned red lines must be enforced or never proclaimed in the first place. None of these are new to history, although it is surprising how often they have to be learnt anew. But do these lessons tell us anything about the way forward? Are there further opportunities that might be missed?

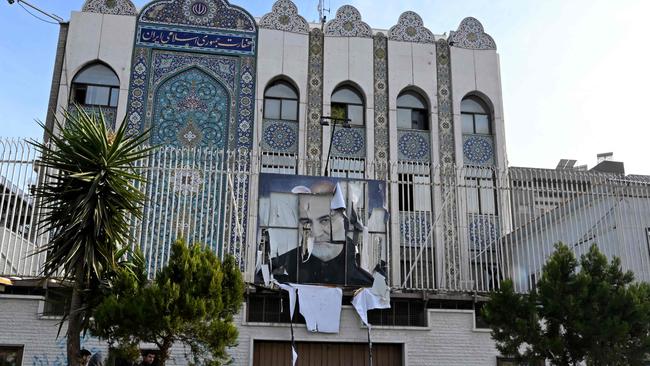

There are at least two. The first is to seize the moment in relations with Iran. Its leaders are in their weakest strategic position since the Islamic revolution in 1979, with Hezbollah pulverised, Assad removed and Israeli military technology far outperforming their own. They are becoming more closely bound to Russia. Beleaguered, they are accumulating more enriched uranium for nuclear bombs.

Yet among Iran’s leaders is a new president who is consistent in speaking of better relations with Gulf neighbours and the West. Whether that is from weakness or from conviction, it should be put to the test. If the incoming Trump administration simply pursues blanket hostility to the whole Iranian political system, it could miss an important opportunity. Western leaders, working with Arab nations, now have the best chance for a decade to limit or reverse Iran’s nuclear program by agreement rather than war.

The second opportunity is, of course, to promote once again a peaceful settlement in Syria, an objective vital to stabilising the Middle East and to reducing flows of refugees towards Europe. For the moment we have to be ready for any eventuality, including military strikes against any revival of Isis and the use of Syria as a base for international terrorism – the US has already carried out such strikes in recent days. But western countries, including Britain, should explore with the new rulers in Damascus their true intentions and whether they have turned decisively against their previous links with al-Qaeda.

If their actions suggest that they have, that they are ready to open talks with the many other opposition groups who hold territory in Syria, and give up Assad’s chemical weapons, assistance from the West should be available to them. If they haven’t, and instead are yet another chapter in a long story of despotic rule, there will be little we can do for them except watch them one day go the same way as the dictator they fought to banish.

For countries such as Britain, some humility and caution will be required. We will be less influential than we were. Our own notions of democracy can only be replicated after the painstaking building of trust between factions – there is no point expecting instant elections. Syria is one of the world’s most complex states, torn between religious tensions, Kurdish aspirations, Turkish intervention and the spillover of politics from Lebanon and Iraq. But 14 years after Assad assured me there would be no trouble, there is at least a chance, with leadership that he lacked, to escape from it.

The Times

“Syria is different,” former President Assad said to me in February 2011. “There will be no rebellion here. Unlike Egypt, we are united by an ideology, of resistance to Israel. There will be no trouble.”