Assad town abandoned to its fate

The Assads belonged to the Alawite sect, which has controlled Syria for decades, but now its members face reproach from the country’s new rulers.

No one used to visit Qardaha, the mountain hometown of the Assad clan who ruled Syria for decades, unless they had to. Its residents had a reputation for arrogance, by virtue of proximity to the ruling family, and resented intruders. Syria, in turn, hated them.

With Bashar al-Assad’s downfall the town now receives visitors every day. The triumphant rebels head straight to the Assad mausoleum, where his father Hafez and mother Anisa are buried. Last Friday, gunmen stamped on the graves and set fire to them. “We need to turn this site into a urinal for every Syrian,” one said.

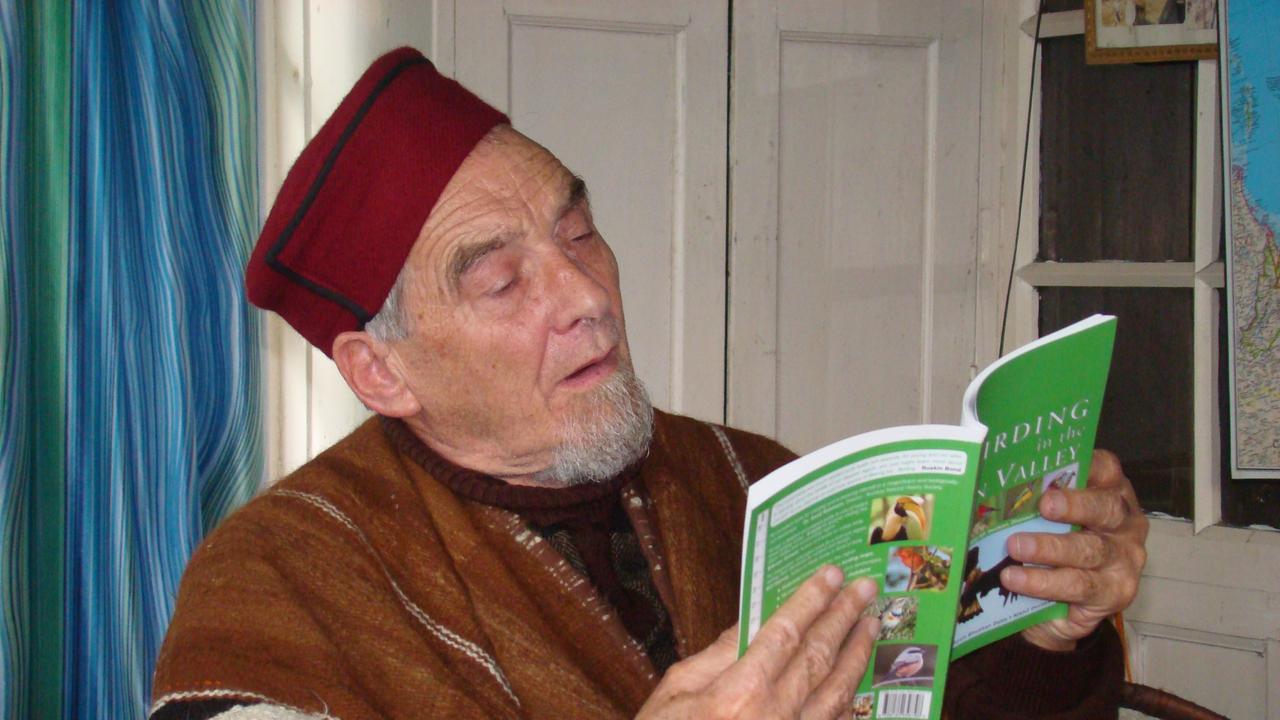

A few miles away at the town’s large mosque, Sheikh Ghassan Hamdan was in an office with some younger men from his and Assad’s Alawite minority. Like everyone else in the shuttered town, their fear was palpable.

For decades, the Alawites had controlled Syria and the protests against Assad in 2011 quickly turned into an overtly sectarian civil war. Many Alawites now feel that Assad, who demanded they fight and die for his regime, has abandoned them to their enemies.

Hamdan insisted that there was nothing to fear. “No one has been lynched, neither in Latakia [the main Alawite city] or elsewhere,” he said. A young man interrupted to say he had heard of lynchings and Hamdan snapped: “Don’t contradict me! Don’t say anything that causes trouble.”

He turned away to answer a phone call. “You want me to be honest?” the young man asked a Times journalist. “Yes,” there were threats, he said.

Like many Alawites, Hamdan said Assad had abandoned to chaos the community that makes up about 10 per cent of Syrians but controlled the levers of power for decades.

The treatment of the minority is a litmus test for the new rulers led by Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, who now goes by his birth name of Ahmed al-Shara and is seeking to present a more moderate face to the world. When The Times visited Qardaha and Latakia, his fighters manned a few checkpoints but appeared to have been under strict orders not to interfere with the residents.

Shara and his lieutenants say that Alawites will not be treated unfairly, and have made a show of meeting the heads of Syria’s minorities. But the assurances are often followed by a promise to hold the regime’s former cronies accountable, with the implication that many will be Alawite.

One woman in Qardaha insisted that “everything is great.” Other residents had come out with buckets of paint to whitewash the old Syrian flags on store fronts. “White represents love and peace,” said one disconsolate man, as he painted over a flag. He said he had heard the rumours about revenge killings but not seen any. “I hope it stays like this. We have always lived in poverty,” he said. “Citizens here, their only job was joining the military.”

Many of them died for that. The Syrian civil war is estimated to have killed about 500,000 people, almost a fifth of them Alawites. Every family would have lost a relative fighting for Assad.

“We are happy to see him go. He impoverished us,” Nahla, an Alawite widow who lives in Latakia, said.

There have been celebrations in Assad’s former stronghold, a mixture of genuine support for his demise and a desire to show that Alawites were as happy to see him go as any other Syrian.

But Nahla said: “I’m not going to clap for people I don’t know yet.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout